I like to lay claim to being a digital nomad ahead of my time, using the flexibility I had with online school as an adolescent to lasso the privilege of my dad’s frequent travel and wanderlust approach to life. I would turn in my chemistry homework through the questionable wifi of the Grand Canyon’s North Rim camp shop, snowboard Mt. Hood (spectacularly poorly) in the morning and write my college application essay by a Best Western lamp at night. I had trekked through Zion three times before I was 19.

But I’ll likely never be able to pursue that route of adventure with such ease again. The days of rolling into a national park and seeing the sights are from a bygone era. Now, if you hope to see the sweeping 360 degrees of Angels Landing, you have to enter a permit lottery up to three months in advance. Eight of America’s national parks have opted for this ticketing system in 2022, particularly for their most popular trails. The limits aim to reduce congestion, protect the terrain and uphold safety, which became meteorically harder to do during the pandemic.

A COVID-driven bump saw 160.7 million Americans participate in at least one outdoor activity in 2020 — 7.1 million more people than in 2019. That’s about 54% of the U.S. population older than six.

Despite the boom, outdoor recreation frequency has been declining for nearly a decade according to the Outdoor Industry Association (OIA), which collected data from more than 18,000 people for their research last year. From 2012 to 2020, the average number of outings Americans took per year declined from 87 to 71. This covers every outdoor activity from fishing and camping to swimming and even basketball. OIA Research Director Kelly Davis thinks it may have been declining long before the research started.

OIA’s 2021 Outdoor Participation Trends Report found that people are looking for fewer and fewer outdoor experiences each week. The organization’s leaders worry that as many as one-quarter of new participants won’t continue to participate next year as they return to their pre-pandemic hobbies, habits and air conditioning. Davis speculates about the role social media has played in the decline. People are seeking more one-off experiences and status symbols, and no longer identifying with the sports themselves.

She asked me to close my eyes and imagine a hiker. “Who do you see?” I described to her a woman, with a backpack on and tall calf socks. My first image of a hiker was young and white. She laughed, “Are you describing yourself?” It was only mildly embarrassing.

But she said what I described was a popular archetype of the activity, an archetype informed by who the sport’s “core” members were for decades. Core members being people who do the activity with intensity, maybe almost every day, and maybe only specifically that activity. It’s their lifestyle. Think of the Alex Honnolds of the world.

They’re becoming few and far between. And that’s quite okay.

What’s happening is more people, and more types of people, are pursuing outdoor recreation. Participants are more diverse in terms of race, income, age, location and interest. They’re trying a range of activities and not committing to just one in particular. Davis thinks the outdoor industry, from employers down, needs to diversify too. “In the market economy, the brands that adapt to their target audiences’ needs will survive and thrive. And the ones that do it first will thrive even more,” she says. “The ones that fail to adapt will die.”

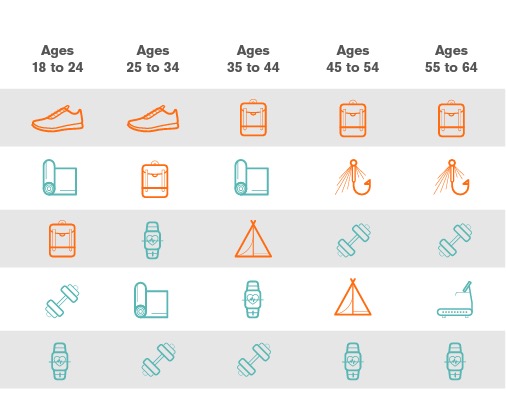

Top Outdoor Activities By Age Group

Data courtesy of the Outdoor Industry Association

She described how companies have already hired their core audience, so often the people who spent the most money on the equipment, excursions, travel, passes and so on. But there are still other steps. “There are more ways to be diverse than simply just having a myriad of colors on your workforce,” she says. She pointed out that the 55-and-older population is going to grow by 45 million in the next two decades, and in the past two years has made up 15% of participants. That population and their interests need to be catered to as well as the expanding younger audience.

Who Wants to Hike, and Who Gets To?

The future is becoming increasingly clear. Yes, there are more people to spend more money, but that wasn’t the case in 2020. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reported that the outdoor recreation industry economy decreased from 2019 to 2020 by 17.4%.

The BEA attributed the decline of the industry from 2019 to stay-at-home orders. In 2020, 37.4% of nominal value added came from “conventional outdoor recreation” that is, doing the activity. About 45.8% came from “supporting outdoor recreation,” which makes the most money for the industry, but was down by about 4% from 2019. Things like outdoor concerts, amusement parks, lodging and movie screenings as well as gift shops and food fall under this category. This has already risen again in 2022.

The decline seems also to be a confluence between changing demographics and geographies, and organizations following old trends.

The OIA found in its 2021 Outdoor Participation Report that the participants who had increased their activity in 2020 were under 25, lived in southern states and had incomes above the national average. The activities that ranked highest for the 18-24 age ranges were 1) running, 2) yoga, 3) hiking, 4) weights, 5) cardio fitness. The 25-to-34 age group had the same interests, but ranked hiking higher than cardio, and yoga and weights significantly lower. Hiking was predominantly popular with people 35 to 64, and this age group also ranked fishing and camping as their interests instead of running or yoga. (See chart.)

A COVID-driven bump saw 160.7 million Americans participate in at least one outdoor activity in 2020 — 7.1 million more people than in 2019.

Companies are experiencing misalignment in interests and location and missing out on their site selection. Take the state of Florida, which includes almost every outdoor recreational activity you could look for in the South, and you can do them all year long. In 2020 Florida ranked in the top seven states where outdoor recreation contributed most to the state GDP, at an even 3%. Some states that ranked above it were understandably Hawaii, Montana, Maine, and Alaska by a hair. In fact, the entire West Coast and the four corners region ranked lower than Florida, sometimes even by 1.5 percentage points.

According to Conway Data, parent company of Site Selection, most outdoor recreation company projects since 2020 have been in states with moderate to low revenue from outdoor recreation. The projects include manufacturing or distribution centers, headquarters, and offices. States like California and Illinois that have two or more recent outdoor industry projects still had outdoor industry GDP under the U.S. average, at 1.5% and 1.6% respectively. This might not be surprising. States like Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota are known for their manufacturing power but their outdoor activities are naturally limited by weather.

Though participants from the South may not be the “core” many think of, they make up a huge chunk of the market. They’re states with huge race, income, and age diversity and not only make up a diverse consumer audience, but a potential workforce as well. Of the businesses questioned by the OIA, only two headquartered in Florida. Only one was in Tennessee, and only one was in Georgia as well.

For outdoor recreation manufacturing companies, it may seem inconsequential. You can build a kayak in Colorado and ship it down to Florida without a hiccup. However, manufacturing only made up about 14.1% of that $374.3 billion in 2020, leaving much to be desired. It also bypasses passionate, educated talent in southern states with lower costs of production.

The OIA found in its 2021 Outdoor Participation Report that the participants who had increased their activity in 2020 were under 25, lived in southern states and had incomes above the national average.

Southern states have been somewhat underdeveloped in the outdoor industry as companies did like Kelly Davis described and hired their core participants that were in Oregon, Colorado, or California, often people dedicated to an active lifestyle like they marketed to. She described to me a paradox, one where outdoor industry workers are underpaid because it’s understood they’ll get to pursue their outdoor passions through their job or location. But the more you work in the outdoor industry, the less time you get to spend outdoors.

“They only make up about 20% of your target audience,” Davis says. “Unfortunately, they’re probably going to make up about 50% of your revenue. But if we can expand the audience, if you can get more people trying stuff, sales will expand.”