LOOKING FOR A PREVIOUS STORY? CHECK THE ARCHIVE.

Fly Me to the Moon –

and Much, Much Farther

and Much, Much Farther

NASA Aiming for Permanent

Moon, Mars Bases

Moon, Mars Bases

It's NASA's most ambitious move ever. But how will the outer- space future evolve in business- centric areas like profit- making, site selection and infrastructure? A long- time advocate of lunar economic development weighs in. From Earth ... really.

|

| The Martian astronauts have landed: This painting by NASA artist Pat Rawlings depicts astronauts exploring the Noctis Labyrinthus canyon of Mars just after sunrise. |

Choosing to establish a moon base was "a very, very big decision" for NASA, said Scott Horowitz, the agency's deputy administrator for space exploration. Choosing to establish a moon base was "a very, very big decision" for NASA, said Scott Horowitz, the agency's deputy administrator for space exploration. |

| T |

he U.S. is opening up a brand- new permanent location that will have eager job applicants lining up. But there could be one substantial disincentive: the commute. It's going to be a real bear, almost 240,000 miles (384,000 km.) – one way.

Yep, NASA's going back to the moon for the first time since 1972 – and it's planning to stay. What's more, the agency plans to expand well beyond its lunar base, setting up another permanent operation on Mars (see accompanying "Living in Outer- Space Time" chart).

That marks a major shift. NASA's six Apollo moon missions between 1969 and 1972 were there- and- back ventures.

"A base on the moon doesn't sound like a big deal, but it is a very, very big decision," NASA Deputy Administrator for Space Exploration Scott Horowitz said at the project's Dec. 4th announcement in Houston.

NASA weighed a permanent operation against the option of flying a series of individual sorties. A fixed outer- space presence, it decided, offers compelling advantages.

"A lunar outpost," explained NASA Deputy Administrator Shana Dale, "results in a much quicker path in terms of future exploration, allows for maturation of in situ resource utilization, accomplishes many science objectives, and enables global partnerships."

Literally, it's a very far- out project. But Declan O'Donnell, founder of the nonprofit Lunar Economic Development Authority (LEDA), is thinking beyond that. Way beyond.

"The mission is NASA's next logical step – just for this decade, to establish a base on the moon," O'Donnell told The SiteNet Dispatch.

But the long- time supporter of outer- space development says there's a veritable Milky Way's worth of thorny lunar issues looming. O'Donnell, for example, foresees "the need for venue- wide lunar standards for development, construction, building maintenance and property rights." A moon economy will also need a "space bank" with "space money," he added. (See accompanying "What on Earth Is Space Money?")

Notions like that may prompt some observers to dismiss O'Donnell's ideas as science- fiction fantasy. But, then, it hasn't been all that long since the notion of a permanent moon base was considered fanciful fiction. And O'Donnell provides a point of view that, however unconventional, illuminates some major questions that may – and quite possibly will – emerge in outer- space development. Corporate site selection is one of them.

Searching for a Site on the Moon

|

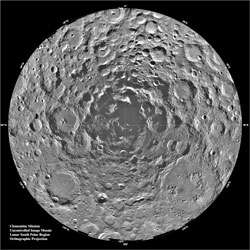

| The current frontrunner as the moon- base site is the satellite's south pole, pictured in this mosaic composed of 1,500 images taken by NASA's Clementine lunar orbiter. |

Declan O'Donnell (pictured), founder of the Lunar Economic Development Authority, favors a lunar base "on the far side of the moon, near the solar system's largest proven deposit of titanium." Declan O'Donnell (pictured), founder of the Lunar Economic Development Authority, favors a lunar base "on the far side of the moon, near the solar system's largest proven deposit of titanium." |

"We know very little about the moon's poles," said Dale. "In fact, we know more about Mars than the poles."

Even so, one south pole area is the strong early frontrunner for the base site.

"There is an area on the edge of Shackleton Crater that is almost permanently sunlit a very high percentage of the time, 75 to 80 percent," NASA Deputy Associate Administrator Doug Cooke explained. Nearby, he continued, sits a 300- acre (120- hectare) flat tract that could serve as a natural landing pad. "There could even be cometary ices that have lain there for billions of years," Cooke added. That area, he noted, could hold helium- 3, a rare element that could be suitable for producing nuclear fuel to power return moon missions. The south pole locale may also contain volatile gases that could prove useful in commercial ventures, NASA believes.

In contrast, the LEDA envisions an altogether different base site.

"What LEDA has been proposing to sponsor or otherwise cause is a permanent base on the far side of the moon (that's always turned away from Earth), not at the poles," O'Donnell explained. "That location is near the solar system's largest proven deposit of titanium, as NASA knows."

That lode would be the LEDA site's principal economic driver.

"The titanium would be mined and used to build spaceships to go the Mars," said O'Donnell, a Denver- metro attorney who specializes in tax and securities law, with a strong interest in space law. "The lunar architecture's predicted centerpiece would be a large shipyard, a company town and an electronic catapult to propel materials into cislunar orbit" (where the moon and Earth's gravitational pulls balance). The LEDA's idea for a

|

| This painting by NASA artist Robert McCall pictures what a lunar mining operation might look like. |

|

| NASA hopes to learn much more about the lunar poles through the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (pictured above in a NASA rendering) which has a planned launch date of 2008. |

While strikingly dissimilar, those two moon- base visions may not be mutually exclusive. O'Donnell thinks that Earth's satellite over time could conceivably be home to both a "NASA town" and a "company town" dedicated to private- sector ventures.

Funding Issues Could

Cloud Mission's Future

"That's not to say that [the south pole site] is the final choice or anything," said Cooke. "But it is one that we probably know most about at this point until we fly a lunar robotic orbiter."

NASA isn't projecting that it will land at the base site until 2018. In the interim, the agency will fly a series of unmanned moon intelligence missions. The first is the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which is scheduled to launch next year. The LRO will circle the poles searching for natural resources that could support the moon base. The robotic craft will also carry a smaller satellite that will be deliberately crash- landed in the Shackleton Crater in 2009. Onboard sensing equipment will analyze dust from the crash's impact for evidence of water.

Funding issues, however, could crash the entire moon- base mission. NASA hasn't yet provided a price tag. President George H. W. Bush, however, led a 1989 study that estimated that establishing a permanent moon presence would cost at least $500 billion. That outlay was so sizable that the study was largely ignored and soon faded from view.

Many of the NASA ventures that have successfully secured funding have been roundly criticized for recurrent cost overruns and delays. The International Space Station (ISS) is often cited as Exhibit A. Initially projected

|

| Critics of recurrent cost overruns on space- related projects often cite the International Space Station as a prime example. |

Such exponential inflation has drawn considerable criticism from the likes of Taxpayers for Common Sense (TCS), a watchdog group that targets wasteful U.S. government spending. TCS advocates major cutbacks in NASA's budget.

"While the space program yielded many successes in years past, taxpayers are no longer getting their money's worth from a program that focuses on repeating the deeds of yesterday," the group asserts. Much of that funding, TCS contends, should be redirected into "high- priority scientific research such as astrophysics, Earth remote sensing and aeronautics." As for NASA, TCS says that it "should use new technologies to build a better space program at less cost."

"Without a price [on the moon- base mission], you'll end up wasting money," said TCS Vice President Steve Ellis.

NASA: No Additional Funding Needed

"The Vision for Space Exploration

|

| Government watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense is backing major cutbacks in NASA's budget. (Pictured: NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.) |

NASA's current annual allocation is $16.8 billion. The agency anticipates significant additional revenues for the moon- base program from international project participation, and from the 2010 completion of the ISS and the subsequent retirement of the space shuttle.

But what if NASA finds at some point that it doesn't have sufficient funds for the moon- base mission?

"We go as we can afford to pay," said Dale. Until funds are in place, the project timetable will have to move back, she explained.

"Funding could end up being problematic," O'Donnell observed. "But if they make it an international project, it would have a chance."

NASA seems to be counting heavily on other nations' involvement – and private industry's as well.

"It is critical that we have international participation and commercial participation along the way," Dale noted. The project's "open architecture," she added, "welcomes the participation of other countries around the world as well as commercial entities."

The ISS experience, however, could dim some nations' eagerness to take part in the moon- base mission. A number of the space station's 14 partner countries have complained that U.S. priorities have dominated the project. The U.S. conceived and designed the ISS.

But NASA has involved other nations much earlier in the

|

| NASA's new plan for space exploration "is not an increase above our baseline budget," said Deputy Director Shana Dale. |

| NASA says that other nations have been involved in depth much earlier in the moon- base project than in the often criticized International Space Station. (Pictured: A NASA rendering of a lunar outpost.) |

|

"I think one of the points that has really resonated when we have talked to other countries is bringing them in so early in the process," Dale noted. "They really were here in terms of the ground floor in the development of the themes and objectives."

"We have all learned through our past experiences," added Cooke. "[The moon- base mission] is not one integral vehicle like the space station. So there are a lot more options to work with, we feel [including] parallel developments."

Current Treaty Could Curtail

Profit- Making in the Cosmos

The key private- sector issue centers on one particular section of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, widely regarded as the legal structure governing outer space: "The exploration and use of outer space," the treaty states, "should be carried on for the benefit of all peoples, irrespective of the degree of their economic or scientific development."

"That's the riddle," explained O'Donnell, who's also president of the World Space Bar Association. "In international treaties, that clause means profit- sharing. Any profit you make you'd have to divide in some fashion with the 200- odd nations and territories on Earth."

Individual countries could unilaterally skirt that provision by opting out of the Outer Space Treaty. The pact provides that any of the accord's 124 signatory nations can withdraw by giving notice. A withdrawal would become official a year after notification. But bailing out isn't a realistic alternative, O'Donnell feels.

"A permanent outer- space base isn't going to become part of America," he contended. "There are too many people who have an interest. And if you divide the moon between nations, you're just looking at more wars, only now in space. It's got to be an international thing."

The Outer Space Treaty echoes that point. Space, it states, "including the moon and other celestial bodies is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty."

"Redefining the treaty's definition of

|

| The signing of the 1967 Lunar Space Treaty (pictured left) came six years after Alan Shepard became the first NASA astronaut to blast off for outer space (below).

Treaty- signing photo: Saskatoon Public School Division |

|

Work on redesigning the Outer Space Treaty should've already begun, O'Donnell contends.

"The treaty calls for a new government as soon as space development becomes feasible – which is now," he noted. "But nobody's come up with a new government."

Building a Railroad

And a 'Cycler Orbiter'

Characteristically, the LEDA already has several initial developments in mind.

"You've got to create an infrastructure so the people who come later don't trample the hell out of the lunar surface," O'Donnell said. "The first project should be a circumferential lunar railroad, which will limit needless trespass. Much of the railroad would be underground to protect it from asteroids."

NASA's plan calls for a "mature transportation infrastructure" to be in place on the moon by 2025.

The LEDA is supporting another major construction project that wouldn't really be on the moon. It would be a "cycler orbiter," originally championed by Eugene "Buzz" Aldrin, a member of the LEDA board of advisers and the Apollo 11 astronaut who joined Neil Armstrong in 1969 in first setting foot on the moon.

"The orbiter would be a saucer- shaped vessel, a mile (1.6 km.) in diameter and three miles (4.8 km.) in circumference," O'Donnell explained. "All of the nations participating in moon development would have operations there. Eventually, it might become the capital for space governance and the headquarters for all space development industries." Orbiter- based operations, he contended, "can escape benefit- sharing."

The LEDA's orbiter design features five different levels. Separate planes would be dedicated to the ship's managerial operations; living quarters for permanent residents and crew members; farming and ranching

|

| Here's a mockup of the Lunar Economic Development Authority's idea for a lunar orbiter. |

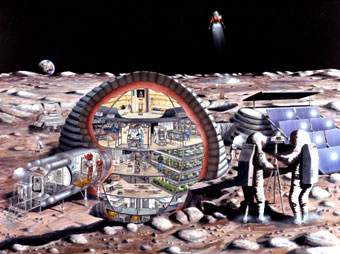

For the private sector, some of the most promising lunar locations could lie beneath the satellite's surface. Underground moon areas could provide quality sites for industrial operations and housing, O'Donnell contends. Those human settlements could receive oxygen seeping up from plants growing immediately below them, he explained.

"Most of the safe living will be underground," said O'Donnell. "If you go down six feet (1.8 meters) into the moon's surface, it's 70 degrees Fahrenheit (21 degrees Celsius) 24 hours a day. And it's 70 degrees for a long way down.

"From a site selection perspective," he continued, "businesses are going to have to plan on digging a lot deeper than they're used to get sufficient space for below- ground operations."

O'Donnell contends that current outer- space treaties would allow businesses to lease their lunar sites.

"Leasing property on the moon shouldn't be a legal problem," he said. "A lease wouldn't violate the treaty's sovereignty provision and operations on leased land wouldn't use up the moon's resources."

|

Are the moon's most promising sites located beneath its pockmarked surface? |

| Although NASA hasn't said what it might build on the moon, one of the agency's concepts is the inflatable dome pictured in the rendering above. Spanning a diameter of about 53 feet (16 meters), the habitat could house as many as 12 people, with facilities for exercise, operations control, clean up, lab work, hydroponic gardening, private crew quarters, dust- removing devices for lunar surface work, an airlock, and lunar rover and lander vehicles. | |

Packing for Mars

On the other hand, humans' cosmos- related IQ could grow substantially over the next few decades, given NASA's ambitious strategy.

|

| "You have to realize we haven't left low Earth orbit in the last 30 years," said Steven Squyres, a Cornell University professor and NASA researcher. "We need some place to flex our deep- space muscles again before we go zooming off to Mars." |

|

| NASA's Mars Global Surveyor sent back images like the one above that suggested the presence of liquid water on the planet's surface. |

|

| Prominent scientist Stephen Hawking equates successful space exploration with the continued existence of the human race.

Photo: British Council United States |

"This is a living document," Horowitz said of the open- endedness of NASA's moon and Mars blueprint. "We are going to learn a lot from these [unmanned robotic] missions . . . that will advise and be fed into decisions."

NASA currently has two rovers, Opportunity and Spirit, that have been exploring Mars' surface for almost four years (initially, they were expected to survive for only 90 days). The agency is also getting substantial Martian information from the Mars Global Surveyor that's circling the planet.

The Surveyor craft sent back images in mid- December that suggested that liquid water was present on the planet's surface. That, in turn, intimated that Mars at some point possibly accommodated some sort of life form.

That information reinforced some scientists' contention that Mars offers a bigger payoff than the moon.

"It would just be unfortunate to lose momentum with all these very exciting Mars discoveries toward the middle part of the next decade," said Ray Arvidson, a Washington University professor and the deputy principal investigator for the Mars rovers program. "Those become very difficult to do in the constrained financial environment because of the re- emphasis of the moon," he noted at the American Geophysical Union's (AGU) conference in San Francisco on Dec. 15th.

In contrast, Steven Squyres, a Cornell University professor and the principal scientific investigator for the Mars rovers, continues to support the lunar base.

"I'm a big fan of sending robots to Mars," Squyres said during an AGU conference panel discussion that also included Arvidson. "But I firmly believe that the best way to explore Mars is going to be with humans.

"You have to realize we haven't left low Earth orbit in the last 30 years," he continued. "We need some place to flex our deep- space muscles again before we go zooming off to Mars, and the moon is the obvious choice to do that."

Is Outer- Space Living

Essential for Human Survival?

"It is important . . . to spread out into space for the survival of the species," Hawking said at a Hong Kong lecture in June of 2006. "Life on Earth is at the ever- increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster, such as sudden global warming, nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus or other dangers we have not yet thought of."

Finding a suitable living site, however, may require an astonishing number of frequent flyer miles, he added.

"We won't find anywhere as nice as Earth unless we go to another star system," said Hawking.

"The ultimate thinking," O'Donnell said, "is to set up a base on Mars for the singular purpose of building a fleet of tough ships to get beyond the Oort Cloud, the egg shell containing billions of comets that surrounds our solar system."

Those ships will need to be tough indeed, since they'll be traveling a long, long way. The Oort Cloud is an estimated eight billion miles (12.8 billion km.) from Earth. That's about 2,000 times the distance from the Sun to Pluto. (The spherical envelope of comets is so far away, in fact, that no one yet has been able to actually see it.)

Those long- distance craft would also need to be strong and roomy enough to carry heavy payloads. O'Donnell envisions that some of the ships would carry "thousands of people." Others would ferry a payload that's quite different, but essential for survival.

"To leave our solar system to go elsewhere," said O'Donnell, "we need a fleet that can also take asteroids with it to provide food and water as the ships fly."

But to fly to where, you say?

An excellent question. That destination, though, is one more big thing about outer space that the human race remains a long way from knowing. Much, much farther, in fact, than from here to the moon.

|

| The moon, with Mars off in the distance. |

|

Living in Outer- Space Time:

NASA's Projected Timetable 2007: NASA begins what Deputy Administrator Shana Dale calls "extensive dialogue with other countries about the ways in which they want to participate" in the U.S. agency's new space exploration plan. 2008: NASA launches the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), initiating a new

2009: A smaller satellite carried aboard the LRO is deliberately crash- landed in the moon's Shackleton Crater, near NASA's favored south pole site. The smaller craft is equipped with sensing equipment that will analyze dust from the landing's impact for evidence of water. 2014: NASA begins a series of manned spacecraft missions. The missions will orbit the moon's polar regions, working to identify possible landing sites, natural resources and hazards to the lunar vehicles that the agency is designing. 2018: NASA starts sending four- astronaut crews to land on the moon (see rendering at right). Initially, crew members will stay on the satellite for about a week before rotating back to Earth. 2024: Permanent moon base will be completed. Astronauts will begin living on the moon continually, with crew members staying for longer periods of time – as long as six months. 2030: This is space industry analysts' earliest estimate of when NASA might make its first launch for Mars. The agency hasn't yet projected the year in which it thinks Mars flights will begin. Source, 2007- 24 dates: NASA |

|

What On Earth Is Space Money?

But make no mistake. Eventually, the moon's economy will have to have some hard cash in order to function, argues Declan O'Donnell. And that lunar legal tender won't be similar to any of the currencies now in use on Earth, contends the founder of the nonprofit Lunar Economic Development Authority (LEDA). "People in a lunar settlement at some point will have to barter with something, just as Christopher Columbus did when he first arrived in America," said O'Donnell. "And they'll have to use a totally new kind of currency: space money. It would be created specifically for use on the moon and recognized by all space- faring nations." Earthlings are already spending huge sums of money to get to outer space. Governments around the world are pouring an estimated $50 billion a year into space- related ventures – a 25- percent upsurge from the 2000 tally. Moreover, since 1998, the private sector annually has been outspending the world's governments in the quest for outer space. Why Moon Money? "It would be a lot of different things involving small fees," O'Donnell explained. "Sort of like the fee list that a real estate developer provides when he or she is constructing a condominium." But why create a new currency for space? After all, Earth's global economy

"It wouldn't work," O'Donnell said of using existing currencies. "Eventually there would end up being one dominant currency in space, perhaps the U.S. dollar, and everything would be pegged to that. In the long run, that wouldn't be equitable. "It's just logical that there will be some disasters in outer- space development," he continued. "When that happens, if there's one leading currency, it would suffer tremendously and unduly. It's sort of like a new version of an old saying: 'You cough on the moon, you catch a cold down here.'" Creating a separate space currency would also ensure completion of outer- space projects, O'Donnell contends. "It would be a real blight on humanity to have unfinished structures dangling around on the moon, Mars and other places in space," he said. "But if you had a lunar development authority that had its own bank and issued its own money, you could make sure that people followed through with their outer- space commitments. And if someone didn't follow through, the authority would find somebody else who would." Taxes in Space? "That means that there's good news in that most of the world would recognize the space currency used for barter as normal money," he said. "But there's bad news, too, because they'll want to tax it like all the other money spent on Earth." O'Donnell, though, has another idea on that front: a tax- free state in space. He advocates that user fees, not taxes, fund space government services. And that's an idea that could make space look even more like the land of opportunity. |

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

Site

Selection Online

©2007 Conway Data, Inc.

All rights reserved. Data is from many sources and is not warranted

to be accurate or current.