LOOKING FOR A PREVIOUS STORY? CHECK THE ARCHIVE.

Illinois Lawmakers Consider $2.6B Clean-Coal Lode

An artist's rendering of what the Taylorville plant would look like.

The Land of Lincoln has big-time opportunity knocking on its door — a pair of "clean-coal" projects worth $2.6 billion. But that door won't open unless Illinois lawmakers create the key.

| T |

he devil's often in the details in blockbuster deals. Just ask business recruiters in Illinois, where some particularly devilish legislative details are coming to a crossroads.

At stake for the Prairie State: two heavyweight "clean-coal" deals — the US$1.1-billion Christian County Generation (CCG) plant and the $1.5-billion FutureGen facility.

Central Illinois has already established itself as a top-tier contender for each separate project. For one of them, in fact, it's the final choice.

Coal- burning plants still supply more than half of U.S. energy.

Photo: Clean Air Task Force

Photo: Clean Air Task Force

All of that could change dramatically, though, if the General Assembly doesn't amend the Illinois Public Utilities Act. Without those changes, the Land of Lincoln will almost certainly drop off both ventures' site-selection radar.

The CCG — known as the Taylorville Energy Center (TEC) — is the potential bird in the hand. The Tenaska-MDL Holding Co. joint venture announced early this year that it had firmed up its previously sketchy plans to locate its commercial-scale power plant just outside the small Christian County city of Taylorville. Located 200 miles (320 km.) southwest of, Chicago the TEC would be the first privately owned U.S. plant using integrated gasification combined-cycle (IGCC) technology. By pressurizing coal rather than burning it, IGCC systems greatly reduce air pollution.

"The TEC would be essentially different from the existing coal plants in the U.S.," John Thompson of the Clean Air Task Force, a Boston-based environmental group, tells the SiteNet Dispatch. "The process the Taylorville plant would use is fundamentally cleaner; it would set the worldwide standard for what coal technology can be."

According to the Clean Air Task Force, the TEC would have to operate for 65 years to equal the nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emitted by an average coal-fired plant in a single year.

If that figure proves true, the Taylorville plant could factor significantly in the global power equation. Coal's pronounced pollution is a truth as incontrovertible as it is inconvenient. Earth, however, still relies heavily on fossil fuels. In the U.S., for example, while nuclear power is generating reinvigorated interest, it's coal that supplies more than half the nation's electricity. What the TEC could provide is a private-sector model for dramatic cuts in coal-produced pollution.

"The first day that the TEC goes into operation," says Thompson, director of the Clean Air Task Force's Coal Transition Project, "all of Illinois' coal plants are going to look outdated."

But the Taylorville plant's first day won't dawn without changes in state utility regulations. And the TEC faces another hurdle to boot: the Sierra Club's July 9th appeal of the Illinois EPA's June 6th air permit for the project.

For Want of an Amendment . . .

The private- sector Illinois plant, which would employ 200 workers, could take coal gasification into the U.S. industrial mainstream. The TEC would have the capacity to produce 630 megawatts of electricity, enough to power roughly 630,000 homes.

The two U.S. plants that already use IGCC technology are a Florida operation located near Mulberry (top), and an Indiana facility outside West Terre Haute, Ind. (bottom).

Indiana plant photo: Tondu Corporation

Indiana plant photo: Tondu Corporation

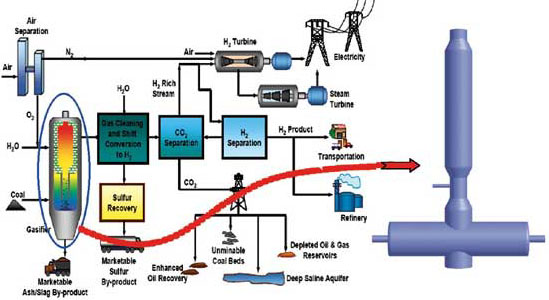

"IGCC pressurizes coal, breaks it down into its component parts and converts it into a synthetic gas," Tenaska Public and Government Relations Director Jana Martin explains in an e- mail interview. "That makes it possible to capture and dramatically reduce harmful pollutants, including mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and particulate matter."

Consequently, the Taylorville plant's turbine wouldn't be driven by burning raw coal. Instead, it would run on the enriched hydrogen gas remaining after pollutants are extracted. The TEC's emissions for a full year will be lower than what many comparably sized conventional coal plants produce in two weeks, Martin avers from the Omaha, Neb., headquarters of Tenaska, the project's managing partner.

First, though, the Illinois General Assembly has to produce its own statutory emission: the Clean Coal Program Law. Initially introduced in February, the lengthy amendment to the Public Utilities Act would allow Illinois power producers to forge long- term sales contracts with utilities.

"Under the current Illinois electric auction process, utilities are precluded from entering into purchase agreements that exceed 36 months," Martin explains. The CCPL would require Illinois utilities to sign long- term "cost- based" contracts with "electric- generating [IGCC] projects [with] a nameplate capacity of no less than 400 megawatts," the legislation stipulates.

If the CCPL fails, in fact, then the TEC is probably a no- go, Tenaska has indicated. The company has declined to comment about whether it would then consider other states.

If the amendment passes, though, the project could begin construction by late this year, says Martin.

"IGCC plant developers need to enter into long- term, regulated, cost- based contracts before plants are built," Martin explains. Those extended agreements are essential, she says, to attract the sizeable private capital needed to finance the billion- dollar projects.

Talk of Contracts and CO2

"The Taylorville Energy Center is a perfect example of a project that uses coal in an environmentally responsible manner. We urge others to support this project," ALA Illinois Director of Environmental Programs Angela Tin said in the association's July 6th announcement. Tin called the proposed plant a "remarkable opportunity to make Illinois a national leader in developing next- generation clean- coal technologies."

"The air we all breathe will be cleaner" with gasification plants, says Illinois EPA Director Doug Scott.

None of that, though, ensures the CCPL's passage. Illinois lawmakers, for example, must resolve the length of utilities' contracts to buy IGCC- produced power. Almost certainly, some legislators will push to sharply limit the deals' duration, arguing that the free market should settle IGCC's commercial fortunes.

Carbon dioxide may also be a significant factor in the legislative debate. The Taylorville plant is designed to capture and siphon off about 20 percent of the emitted CO2, selling it for industrial and commercial use.

The Sierra Club suit contends that the EPA should've more stringently regulated the TEC's carbon dioxide emissions. There are no limits on CO2 production under existing U.S. and Illinois law. In April, though, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal EPA can regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act.

The Sierra Club's suit, however, has drawn fire from a usual ally.

"Appealing the Taylorville air permit is a mistake that makes it much harder to stop global climate change," Thompson, an expert witness in several Sierra Club challenges to coal- burning power plants, said in a July 9th statement. "This appeal delays new technology needed to radically cut carbon dioxide from coal use [and] penalizes technology pioneers." He urged the group to drop the suit and "use their good reputation to encourage Illinois policymakers to help adopt carbon capture and storage sooner on innovative projects like Taylorville."

The TEC's existing design doesn't include "carbon sequestration," which permanently injects CO2 6,000 to 10,000 feet (1,820 to 3,033 meters) underground. Existing IGCC technology can accommodate the capture process.

Initially, Tenaska officials said that such storage technology was prohibitively expensive. Now, though, the company says it will implement carbon capture if the state requires it. The Taylorville area is heavily layered with sandstone suitable for sequestration.

An IGCC system, as shown in the diagram above,

breaks down coal into its component parts by pressurizing it, allowing pollutants to be extracted.

Photo: The National Energy Technology Laboratory

breaks down coal into its component parts by pressurizing it, allowing pollutants to be extracted.

Photo: The National Energy Technology Laboratory

The Case for Illinois Coal

Illinois' coal industry, however, has fared poorly since the Clean Air Act's 1970 passage. With its high sulfur content, the state's coal burns "dirty." Power producers have long opted instead for low- sulfur coal from the U.S. West.

"Coal was once the lifeblood of this town," Taylorville Mayor Frank Mathon told the Illinois legislature earlier this year. "This plant will bring thousands of jobs and more than $1 billion to our community."

"Coal was once the lifeblood of this town," according to Taylorville Mayor Frank Mathon (left). Pictured on the right is one of the many central Illinois coal mines that flourished before the federal Clean Air Act's implementation.

Mine photo: The University of California

Mine photo: The University of California

The TEC's economic impact was outlined in greater detail by a Northern Illinois University (NIU) study released in May. The Taylorville plant "will create more than 1,500 construction jobs, plus hundreds of permanent mining and power plant jobs," lead author and NIU Economist John Lewis said in announcing the report's findings. "Central Illinois will also benefit from a regional ripple effect that will create hundreds of new positions in industries such as retail, hospitality and health care."

The TEC will use 1.8 million tons (1.62 million metric tons) of the state's coal each year, Tenaska says. The CCPL requires the use of "high- volatile bituminous" Illinois coal containing "greater than 1.7 pounds (0.77 kilograms) of sulfur per million Btu content."

The TEC's coal demands would create 160 mining jobs paying about $67,000 a year, including benefits, the NIU report projected. The plant's 200 jobs would pay about $57,000 a year, plus benefits, the study added. The average Christian County job pays $26,415 a year.

On a broader scale, the TEC during each year of operations will produce $355.9 million in economic activity, plus $4.47 million in state and local tax revenues, the NIU study estimated.

The TEC's return could be much richer if the project proves successful. That could demonstrate gasification's commercial feasibility, attracting a large market for central and southern Illinois' plentiful high- sulfur coal.

Lawmakers Sour about Power

TEC Twosome? Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan (right) says that the CCPL legislation initially introduced by Rep. Gary Hanning (left) will reach a vote during this session.

The TEC, however, would reduce Illinois power costs by $190 million per year during each of its first eight years of full operations. At least that's the conclusion of a study by Pace Global Energy Services, a Washington, D.C.- area consulting group.

The CCPL's cost- based contracts will factor into the benefits that the state actually realizes. The cost- based system was developed jointly by Tenaska and the Citizen's Utility Board, a nonprofit advocate for Illinois residential utility customers. If the price utilities pay for TEC- produced power is lower than the market price, Illinois' payoff would increase, Martin explains. Correspondingly, if the TEC's power prices exceed the market price, the project's net value would decrease, she says. In either scenario, though, Illinois ratepayers would realize "substantial savings," says Martin.

The FutureGen facility (pictured in a rendering) is designed to be the first- ever coal- fired electric power plant with virtually no harmful pollution.

When the CCPL will reach a vote remains to be seen. The legislative session thus far has been dominated by issues like the state budget, electricity rates and legalized gaming. Powerful House Speaker Michael Madigan, however, has indicated that the CCPL, as well as the FutureGen legislation, will reach a final vote during this session.

The FutureGen Agenda

DOE officials have given no firm indication of which way they're leaning for the final location. The competition appears to be close. "The top five sites," FutureGen officials noted in announcing the finalists last year, "score within 5 percent of each other."

For the Illinois General Assembly, FutureGen's most significant feature is the plant's carbon storage system. Texas at the moment appears to have a significant advantage vis- à- vis CO2 sequestration. Longhorn State lawmakers in May of last year passed a new law that indemnifies FutureGen against liability for captured carbon dioxide. Texas is the only state that competed for the project that made such an offer. The law stipulates that the Texas Railroad Commission would own all of the plant's sequestered CO2, with the state assuming responsibility for any liabilities. FutureGen's Illinois supporters are hoping that the General Assembly will cancel out that edge by passing a similar indemnification statute.

The state that lands FutureGen will get an economic boost that stretches well beyond the plant's staff of 150. The facility will become the centerpiece of a broad- ranging cluster of innovative power- industry operations, many energy analysts believe.

FutureGen's carbon- capture system is diagrammed above.

A number of major power players are already involved in the project. Since 2005, the federal agency has been partnering in the venture with the non- profit FutureGen Industrial Alliance. The consortium includes U.S.- based firms American Electric Power; CONSOL Energy; Foundation Coal; Kennecott Energy (a part of England's Rio Tinto Ltd.); Peabody Energy; and Southern Company; as well as Australia's BHP Billiton; China's China Huaneng; and England's Group Anglo American.

What the DOE is shooting for with FutureGen is a working IGCC prototype. The commercial- scale plant is designed to be the first- ever coal- fired electric power plant with virtually no harmful pollution. The operation's initial goal is to capture at least 90 percent of COř emissions, project officials say. Over the longer term, though, they hope to eliminate 100 percent of carbon dioxide.

FutureGen's estimated total cost has increased by $500 million from initial projections. Plant development, though, has hit all of the scheduled dates on the project's fast- track timetable. In May FutureGen completed its environmental impact statement. And it concluded public hearings at the four finalist sites late last month.

Meanwhile, the Illinois legislature has its own schedule to meet. At least if it hopes to keep the state in the hunt for the TEC and FutureGen plants.

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

Site

Selection Online

©2007 Conway Data, Inc.

All rights reserved. Data is from many sources and is not warranted

to be accurate or current.