|

Week of December 1, 2008 Snapshot from the Field |

|

LOOKING FOR A PREVIOUS STORY? CHECK THE

ARCHIVE.

Florida’s Everglades Deal:

Sweet and Sour Mash

“I

t felt like you were going to work for the federal government," says Butch Wilson, remembering the day in 1976 when he first set foot inside U.S. Sugar's huge plant in Clewiston, Fla. – today a sprawling 1,700-worker operation that covers 187,000 acres (74,800 hectares). "The first thing they asked me when I went in for an interview was, 'Are you going to stay?'

"That was the old corporate America," continues Wilson, propping an elbow atop a long brown desk inside a spotless conference room at the Chamber of Commerce in Clewiston, population 7,100. "Back then, we were still kind of isolated here. So they didn't want to waste their money and time training you, and then you use that as a stepping stone to move outside this area. They wanted people who were going to stay." Butch Wilson definitely stayed. For 32 years, he stayed at U.S. Sugar's plant in south-central Florida, working his way up to a managerial role in information services. But Wilson's long stay stopped on Oct. 31st of last year. That was the day that U.S. Sugar laid him off, along with 31 other employees, many of them fellow long-timers.

"They said it was because of financial reasons," says the 57-year-old Wilson, who still sometimes says "we" when he talks about U.S. Sugar. "It's all about cost now, about money," he adds, his soft voice devoid of anger. "It's not personal. It's just business." Butch Wilson's tale isn't uncommon in the Clewiston area. After peaking at about 6,800 employees in the 1940s, U.S. Sugar has steadily pared back its Clewiston work force – a reflection of the bitter competitive pills that the entire American sugar industry is trying to digest. "Practically every person here at one time had a relative or a friend who worked for U.S. Sugar," says Wilson, a sixth-generation Floridian. Even now, though, U.S. Sugar continues to be the economic linchpin of Clewiston

Butch Wilson, director of the Clewiston History Museum, stands in front of a U.S. Sugar photograph of three young local ladies positioned in one of the area's sugar-cane fields.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Clewiston Inn was built along the city's Sugarland Highway in 1926. Southern Sugar, a corporate predecessor of U.S. Sugar, built the structure in order to have a place to house its visiting executives and dignitaries.

"The town and the company are one," says Wilson, who's now director of the Clewiston History Museum. "The town is the company, and the company is the town. They're both so intermeshed in one another." Evidence of that connection is ubiquitous in Clewiston. There's Clewiston High's Cane Field Stadium and the city's Candy Cane Park, for example, as well as local tennis courts and swimming facilities – all built over the years with matching grants from U.S. Sugar. In addition, the company also provided financial aid for college scholarships for employees' children, including two of Wilson's sons, who both attained master's degrees. Now, though, the tight bond between U.S. Sugar and Clewiston might be coming undone. A more potent ingredient has been added to the area's sugary mix – Florida's drive to restore the state's endangered Everglades wildlife habitat. The state is nearing the completion of a US$1.34-billion deal to buy the 181,000 acres (72,400 hectares) of land that surround U.S. Sugar's plant (see accompanying "By the Numbers" for details). 'Without the Land, You Don't Have Anything' On one hand, the state's purchase of U.S. Sugar's vast acreage could jump-start the lagging efforts to save the struggling Everglades, the United States' largest subtropical wilderness. Turning the sugar cane fields back into marshes and waterways will help cleanse the ecosystem, carrying fresh water from Lake Okeechobee down to the Everglades. In essence, Florida's land buy could help preserve a national environmental treasure – at the same time strengthening tourism, still the state's biggest industry. On the other hand, though, the Everglades deal has created vast uncertainties in cities like Clewiston, which is nestled

Clewiston Mayor Mali Chamness

Pictured is a part of the vast swath of acreage that Florida may buy from U.S. Sugar.

"We believe in Everglades restoration, but Clewiston and Hendry County should not suffer a negative economic impact," says Clewiston Mayor Mali Chamness, sitting at her desk at First Bank, which lies along palm-tree-lined Sugarland Highway, the city's main drag. Outside, American flags line the road, hanging from utility poles and storefronts and snapping in the morning wind. "Our concern is about the loss of jobs in the future," Chamness continues. "We've become more of a self-sustaining community, but we would not be able to do what we're doing without the jobs that U.S. Sugar provides." For Clewiston, the mayor explains, there's one central question: Can U.S. Sugar survive without the huge swath of farmland around its plant? "We're an agricultural community, and we're proud of the American farmer," says Chamness, who as a toddler in the early 1960s emigrated from Cuba to Clewiston. "Agriculture for over 70 years has provided the economic foundation and lifeblood for thousands of people in this region. The farmers here know that the local economy is all about the land. If you don't have the land, you don't have anything." For the moment, though, the future of the land surrounding Clewiston is buried under a mound of unknowns. And that, the mayor says, has spawned a state of suspended animation. "Everything here is at a standstill now, as I told the governor when I met with him in Tallahassee on Sept. 30th," explains Chamness, a vice president at First Bank. "Work that people had scheduled to have done on their homes and businesses has been cancelled. And in retail, people are hesitant to buy things right now, not knowing what the future is going to bring. Everyone is trying to preserve what they have. It's cut back, cut back, cut back." Over at the Clewiston Museum, Wilson shakes his head and rubs his brow as he considers the welter of unsettling events that's pressing down on his community. "Of all the times for this thing with U.S. Sugar to happen," he says. "For us to be facing this mess this year, with all the uncertainty of the economy."

A local farmer harvests the cane in Hendry County.

U.S. Sugar's corporate headquarters is located in downtown Clewiston.

Can Ethanol Fill the Economic Gap? In seven years, though, that scenario will likely see a radical change. After seven crop cycles, the state is scheduled to begin assuming control of U.S. Sugar's land, initiating the restoration work there. And that's when the big questions begin for U.S. Sugar's facility. Just what does a sugar mill do without any cane fields surrounding it? What can it make? Ethanol, perhaps. U.S. Sugar announced on Nov. 17th that it had "entered into an agreement . . . to explore building" a large ethanol facility in Clewiston, partnering with Warrenville, Ill.-based Coskata. The two firms have been in talks since August about possibly constructing a $400-million plant that would produce 100 million gallons (379 million liters) a year of cellulosic ethanol. "We see this technology as a perfect complement to our existing sugar mill, not to mention a win for the environment, the farming community and for our employees," U.S. Sugar Senior Vice President of Public Affairs Robert Coker said of the potential joint venture. Coskata's public profile spiked up sharply early this year, when the company announced that it had developed a technology to make cellulosic ethanol for less than $1 a gallon. Then in April the fledgling company unveiled plans to build a commercial demonstration plant near Pittsburgh in Madison, Penn., that would produce 40 million gallons (152 million liters) a year of cellulosic ethanol. The companies will ask for state and federal aid for the project, U.S. Sugar officials say. The two firms are likely to find receptive ears in Florida. Gov. Crist has been touting ethanol production as an ideal job-generator if U.S. Sugar shuts down.

'Not a Warm and Fuzzy Feeling' "I think it's a great idea," says Chamness. "I'd love to see us less dependent on foreign oil. But there's not a single ethanol blending facility in the state. That's huge. Maybe in seven years, there will be one in Florida.

Clewiston sits on the southwest banks of Lake Okeechobee (pictured), the nation's second-largest freshwater lake.

"I recently read that 27 ethanol plants have closed lately," she continues. "They're in the Midwest and based on corn. But nonetheless, the fact that they've closed doesn't give us a warm and fuzzy feeling about Coskata." Those reservations are echoed by the Hendry County Economic Development Council (EDC), based in LaBelle, the county seat. "An ethanol plant would be good for the area economy," EDC Grants and Special Projects Director Ron Zimmerly tells the SiteNet Dispatch in an e-mail interview. "Alternative industries must be added to the local area, industries that would not adversely affect the environment and have a meaningful rate of success. But all the negative environmental issues have not been resolved with ethanol. In addition, the outlook for ethanol does not look good at this time for a viable alternative fuel source." Nonetheless, it could be significant for the venture's future that Coskata's ethanol production technology doesn't depend on the controversial use of corn as the central feedstock. An ethanol plant in Clewiston would initially run on sugar cane leaves and excess bagasse, according to U.S. Sugar. But Coskata's flexible technology would give the plant multiple other options if the Everglades deal ultimately eliminated local sugar cane production. The Clewiston plant – which would be the world's largest second-generation ethanol facility – could run on anything from switch grass and wood chips to agricultural waste and garbage, Coskata officials say. Converting to environmentally friendly ethanol would also give U.S. Sugar a much-needed boost in the court of public opinion. The company has been intensely criticized for years for the pollutants created by cane growth and sugar production. In ethanol, though, the company would have a product that, compared with conventional gasoline, could reduce greenhouse gases by as much as 96 percent. Devilish Details

Florida Gov. Charlie Crist has led the state's efforts to buy U.S. Sugar's land.

"Doing something this big is not easy," Gov. Crist told a Nov. 17th press conference held in the Everglades to mark the end of negotiations with U.S. Sugar. "It's hard to envision in the first place, and then it's hard to work through the details." And in this deal, the devil certainly seems to be in the details. Moreover, the process of firming up the project's specifics could be a long time coming, all signs indicate. In the meantime, speculation is running rampant. Unsurprisingly, in the communities that will be most affected, there's a wave of worries centered on what, for them, is the worst-case outcome – U.S. Sugar's shutting down. "Here in Clewiston, there's no doubt that [closing] would be an economic devastation," says Chamness. "It would mean not only the loss of 1,700 jobs at U.S. Sugar, but it would also have a much larger ripple effect in our community." A report released in late July detailed just how big a ripple U.S. sugar's demise would create. The Clewiston plant's shutdown would eliminate 10,711 jobs statewide, according to a study by the Institute of Food and Agricultural Studies (IFAS) of the University of Florida. Ninety percent of that impact, IFAS researchers concluded, would be felt in Palm Beach, Hendry and Glades counties, which would lose 8,935 jobs, plus $1.43 billion in revenue and another $598 million from related business. Residents of Hendry and Glades counties would be hardest hit, with their personal incomes cut by as much as 25 percent, the study found. "We've already felt a crunch over the years with the layoffs at U.S. Sugar," explains Chamness. "Some people who were laid off have left our community or taken lower-paying jobs. "We love it here, and we don't want to leave," she emphatically adds. "We don't want businesses to close or families to leave. We want to preserve our way of life."

U.S. Sugar Senior Vice President of Public Affairs Robert Coker

A Brighter Prospect The outcome will rest on the decisions that are made by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) – the state entity that would own U.S. Sugar's land. The SFWMD must first decide how much of U.S. Sugar's 181,000 acres it needs for Everglades restoration. Then the agency must determine if it's willing to lease enough land back to the company to make the plant economically feasible. Florida Department of Environmental Protection Secretary Mike Sole indicated in June that his agency didn't need nearly all of U.S. Sugar's acreage to achieve the state's goals for Everglades restoration. Perhaps more than 100,000 acres (40,000 hectares) of the land, he said, could be leased back for farming – an assertion that was promptly denounced by some environmental activists. SFWMD officials say that it will take them at least two years to determine just how much acreage they'll need to protect and improve the quality, quantity, timing and distribution of water north of Lake Okeechobee. During that time – and for five years after that – U.S. Sugar would be able to lease back its land and continue normal operations. "It's not the next seven years we're concerned about," says Chamness. "It's the after the seven years. It took us five years here to create the Clewiston Commerce Park, and we have yet to create the first new job. So we know that seven years will be here very quickly." The city's new park did secure an anchor tenant: Bonita Springs-based City Mattress, which in June of 2007 announced that it was going to build a 100-employee manufacturing plant in Clewiston. That project, however, has been put on hold. "City Mattress tells us that they're still planning to come here," Chamness explains, "but they're waiting for the economy to settle down."

'There is Common Ground' "I believe that there is common ground," Chamness emphatically notes. "I believe we can do Everglades restoration and agricultural businesses can continue to operate. "But I don't think any of the affected communities have been given a seat at the table in deciding what happens," she adds.

Sugar cane growing in a field just outside Clewiston.

Raw sugar pours down into one of the warehouses at U.S. Sugar's Clewiston operations.

OTTED may well be fashioning an economic transition plan for the Glades region. Repeated requests for an interview with the agency for this feature, however, went unanswered. Crist likewise has made few public statements about the U.S. Sugar deal. What he has said, though, indicates that he's fully aware of communities' concerns. "It's all about jobs, jobs and jobs. That is so important in these hard economic times," the governor said last month, after the state re-jiggered its agreement with U.S. Sugar to allow the company to keep its plant and infrastructure. "This gives us the opportunity to save jobs while we are saving the Everglades." Crist sounded a similar note after Chamness and Hendry County Commissioner Kevin McCarthy visited him on Sept. 30th to voice their concerns: "Jobs in the area are critical to the future of the region," Crist said in a statement. "To complement a sustainable agricultural industry moving forward, jobs must be maintained." For U.S. Sugar, at least, the Everglades deal offers a more concrete outlook. The sale would provide the company with a massive influx of cash flow – as well as a window in which to mull over its options. "At the end of seven crops, we will either continue to operate the facilities or sell them based on the best interests of our shareholders," Coker said as the revised sales agreement with the state was announced on Nov. 17th. "Every employee we have today, we plan to keep on," he said. Still, sugar operations aren't faring well in the United States. From 1996 to 2007, the American Sugar Alliance has reported, 34 cane and beet mills closed – roughly 40 percent of the total U.S. industry. 11th-Hour Offer Adds Further Complication The deal might not happen. Another potential buyer has mounted an 11th-hour offer. The Lawrence Group, one of the largest owners of U.S. farmland, on Dec. 1st made a formal bid to buy all of U.S. Sugar.

Gaylon Lawrence Jr. of the Lawrence Group, which has made a late bid to buy U.S. Sugar.

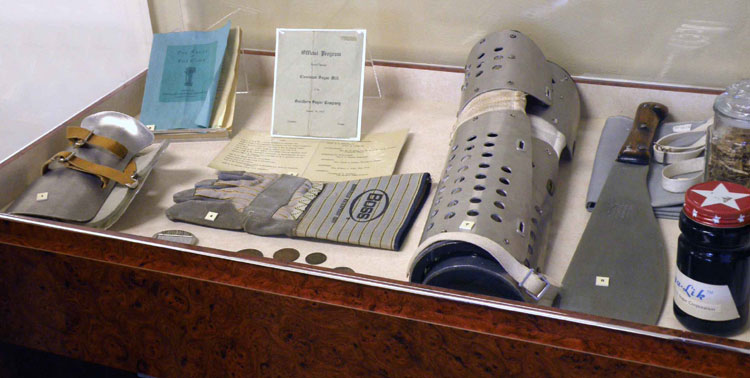

"The Lawrence Group is committed to sell to the SFWMD the land it wants and needs for Everglades restoration purposes at a far lower cost to the taxpayers than would have resulted in either of the two proposals from U.S. Sugar management," Gaylon Lawrence Jr. said as the bid went out. "There is no question that our formal offer and commitment to operate U.S. Sugar for years to come will save jobs and avoid the devastation of local Glades economies, home values and tax bases that would likely occur under U.S. Sugar management's proposal." U.S. Sugar officials have played down the significance of the Lawrence Group's bid. Coker called it "a swiss cheese offer." The company's offer, he pointed out, included a clause that identified the bid as a "non-binding indication of our interest." Meanwhile, The Sugar Cane Growers Cooperative of Florida (SCGCF) has voiced its opposition to the state's proposed purchase of U.S. Sugar's land in a Dec. 1st letter to the SFWMD board. "The deal as currently constructed," wrote SCGCF President and CEO George Wedgworth, "would imperil the very livelihoods of the small and medium-sized farmers who make up the cooperative by turning USSC into a super-competitor, especially given the diminutive lease-back rates and [U.S. Sugar's] ability to pay off its reported hefty debt." U.S. Sugar's $50 per acre costs for leasing back its land are three to four times less than the going rate, the SCGCF charges. The co-op contends that it would be willing to lease the land for as much as $150 an acre. Deadline Looms for Decision And that leaves Glades region communities right where they've been all along – still on the sideline, pondering a future that they've had no power to shape. "Our voices have not been heard at all," says the Hendry EDC's Zimmerly. "It seems as if people – families and their needs – are being overlooked in order to satisfy the perceived need to restore the Everglades. "Who will restore us, if that is possible?" The Clewiston History Museum displays many of the tools cane-field workers used before the advent of mechanized harvesting, including shin guards, gloves, wrist guards and machetes.

|

||||||