Week of July 7, 2009

Week of July 7, 2009

Special Report |

Week of July 7, 2009

Week of July 7, 2009

Special Report |

|

LOOKING FOR A PREVIOUS STORY? CHECK THE

ARCHIVE.

Setting Up Shop at a Dangerous Site: A methane gas explosion blew the roof off a Ross department store in downtown Los Angeles on March 25, 1985, dominating the city's news. Windows in stores a block away were shattered, and Los Angeles police evacuated a four-block area around the site of the blast.

Image: Los Angeles Times

When

Due Diligence Isn't Enough Site selection can be a very complex and risky business. A wrong decision can trigger a heavy toll in time, money and litigation. Pro-actively anticipating and addressing site challenges provides the best preventative, a prominent architect advises.

by Dean Vlahos

Partner and Director of Architectural Forensics WWCOT Architects editor bounce@conway.com A fter the credit-market dust settles, you might find yourself looking out the window of a downtown high-rise and wondering: Where will my company find its next opportunity to develop a new site?

In all likelihood, you will eventually find that opportunity, though the site may not be where you'd expected it to be. But while you're looking for that location, keep one important caveat in mind: Remember that an inordinately strong dose of care is very advisable in assessing potential locations and sites. History is filled with cautionary tales of property developments that went wrong — sometimes disastrously. You may recall, for example, when the Ross clothing store exploded in 1985 in the Mid-Wilshire section of Los Angeles due to a methane gas leak. Or, more recently, you may remember the 2007 controversy that surrounded Japan's Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant. When the Chūetsu Offshore Earthquake struck on July 16, 2007, Tokyo Electric Power Company discovered that it had unknowingly built the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear facility — the world's largest in terms of capacity — right on top of an active seismic fault. The quake triggered radioactive leaks from the reactor into the Sea of Japan. Consequently, national officials ordered a complete shutdown of the plant that lasted for almost 22 months.   A Site Selection Gone Awry: Japan's Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant (left) was damaged (right) by 2007's Chuetsu Offshore Earthquake, which measured 6.8 on the Richter scale. The quake triggered a leak of some of the radioactive material inside the plant, which spilled into the Sea of Japan. Photos: Tokyo Electric Power Company Such dire outcomes raise a red-flag question: Could those companies have avoided those calamitous scenarios through proper site-selection analysis? The answer, unfortunately, is no, not always. Finding desirable, well-located sites that are absent of environmental, archaeological or ecological issues has become increasingly difficult. In fact, companies that want to develop new sites in the current market often have very little choice but to consider brownfield or other less-than-perfect sites. The question for today's property developers, then, is no longer, "How do we avoid problematic sites?" Instead, the question is, "How do we adequately anticipate and address challenges from the beginning of a project in order to save time and money, as well as avoid litigation?"

Arsenic in the Water: Site selectors must be aware of potential pre-existing conditions such as arsenic in the water. Pictured is a pool of water in India in which researchers recorded high concentrations of arsenic.

Photo: ENVIS Centre on Biogeochemistry, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Choosing a Site and Coping With Pre-Existing Conditions

For example, soil in areas that have been utilized for agriculture usually contains high concentrations of agricultural residue (e.g., animal waste) and pesticides (e.g., DDT). Aerial photographs of dairy cattle yards in the Midwest, for instance, may show the presence of decades of animal waste material and dead animals. Such decaying materials produce methane and other toxins that will require extensive cleanup before a site is developed.

Asbestos in the Rock: Asbestos can be present on site in serpentine deposits below the surface. Pictured is part of the Clear Creek Management Area in California's San Benito and Fresno counties, which contains one of the world's largest naturally occurring asbestos deposits - an area covering 31,000 acres (12,400 hectares).

Photo: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Mother Nature has also created toxins in the soil of other agricultural sites. One of those toxins is arsenic, which naturally occurs in some groundwater. If that groundwater were used for dust control, it would spread contaminant over the entire site. In addition, there are areas where asbestos is naturally contained within serpentine deposits. This too represents a potential health hazard, as the material could be released into the air by any earth-moving operations initiated in developing such a site. Urban locations present a different set of challenges for property developers. In densely populated areas, knocking down or relocating residences is seldom an acceptable solution because of the tumultuous impact it would have on residents. That constraint significantly narrows the possible choices for developers seeking to build an urban project. The limitations noted above are only some of the restraints that developers may face at a new location. Given such potential constraints, then, what is a reasonable procedure for a developer to follow in investigating a potential undeveloped site? Expanding enterprises can tap a number of sources to get background data in assessing a site's potential feasibility. Those sources include archaeological records, and geotechnical and historical data. Relevant archive documents also provide useful background information. In addition, a developer can initiate a number of procedures for analyzing a potential site, such as conducting an historical land-use analysis via aerial photographs. Such pro-active steps are certainly valuable. By no means, though, are any of them a panacea. The fact remains that even the most detailed site investigations will not eliminate every potential challenge that developers could face along the way. The Significance of Site Context in Toxic Substance Cleanup and Mitigation One case study that demonstrates the importance of context revolves around the development of the Los Angeles Police Department's Metro Bomb Squad facility, which opened in February of 2008. During the construction of that downtown facility, an abandoned underground fuel oil storage tank delayed construction and resulted in increased costs for cleanup activities. That tank's existence was not readily apparent by site observations or city records. Surface utility connections to the underground tank had been successfully removed years earlier, leaving no indication of its presence.   Big Problems in an Undetected Underground Tank: A crew works on removing the underground oil storage tank (left) that delayed construction and increased cleanup costs in building the Los Angeles Police Department's Metro Bomb Squad facility (right). The tank's presence wasn't apparent from site observations or city records. Photos: WWCOT Architects As a result, the concentration of fumes triggered by project construction during excavation forced the evacuation of the surrounding neighborhood, including a church and a school. The fuel oil at that site reached the groundwater, creating a plume of hazardous material that had spread several hundred feet under the adjacent properties, requiring remediation. (California now requires today's underground storage tanks to have a double-wall containment to prevent this unknown discharge into the soil.)

One Big Jail: The 1.5-million-sq.-ft. (13,500-sq.-m.) Twin Towers Men's Central Jail in Los Angeles houses maximum security inmates and a large portion of the county's inmates with mental health issues. Photo: The Los Angeles Police Department The construction of the 1.5-million-sq.-ft. (13,500-sq.-m.) Twin Towers Men's Central Jail in Los Angeles provides another case study illustrating how the context of a property can loom very, very large during the building process. The Twin Towers jail site has a historic context that stretches back for decades. Back in 1973, that property was a vacant parking lot downtown. But soon the tract was scheduled to be supplanted by a planned four-story office building with two levels of underground parking. That office development, however, was abandoned due to financial challenges. The site remained empty until 1988, when the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department purchased the property with the intent of constructing the Twin Towers complex, which was valued at US$350 million. The project team used historic photographic evidence of the site to conduct its overall investigation. That study revealed that the property had been an old city Department of Water and Power transformer manufacturing plant and storage area that included a 250-foot (76-meter) tall chimney stack. After extensive soils analysis, it was determined the site contained over 6,000 cubic yards (4,560 cubic meters) of heavy metals along with a mat foundation measuring 120 feet by 120 feet by 25 feet (40 meters by 40 meters by 7.6 meters). But the project team building the Twin Towers devised a creative solution to overcome the obstacles that the site presented. One part of that strategy lay in removing and replacing the soil on the property. It would have been cost-prohibitive, however, to remove the foundation or use it as a gravel base for construction. So the designers instead formulated a plan to use the existing mat foundation as part of the new building's foundation. In early 1996, eight years after the LAPD purchased the property, the Twin Towers facility opened. Methane, Fault Line Stall School Construction for Six Years

A Very Long Real-Life Lesson: The presence of methane gas on site and the later detection of a fault line delayed construction of the Edward R. Roybal Learning Center (pictured) for six years.

Photo: WWCOT Architects The genesis of the Roybal Center, however, took shape many years earlier. In August of 1992, the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) authorized the purchase of a 35-acre (14-hectare) site adjacent to downtown Los Angeles for the construction of a new high school. But when construction of the facility got underway in 1999, deposits of methane gas and toxic hydrogen sulfide gases were discovered below the site. That necessitated the suspension of project construction while the state of California conducted environmental testing, assessing the extent of the contamination. During that testing, state officials then detected an earthquake fault line that extended under two of the newly constructed buildings. Rather than abandon the project, the LAUSD revitalized construction in late 2005. The school system devised a comprehensive remediation plan that included demolishing several of the structures affected by the seismic fault line. In addition, the LAUSD installed a passive methane mitigation system. That high-tech methane mitigation system included several components to enhance the site's safety. One of those components came in the impermeable layers that were incorporated over the site to block methane from entering the ground and disseminating through the air. In addition, the LAUSD's mitigation system includes sensors that detect methane build-up, activating fans in any perforated pipes. The lessons learned from these three case studies, then, graphically underscore how important it is to evaluate a potential project site within the context of its location.

A Park Rises in Downtown L.A.: The campus of the Edward R. Roybal Learning Center includes Vista Hermosa Park (pictured), the first new public park in the downtown Los Angeles area since 1895. Funded and developed in part by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy and operated by the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, the park contains a soccer field that the school and the surrounding community share. Photo: WWCOT Architects As these project scenarios demonstrate, proper due diligence should always be performed prior to the start of construction. If site analysis indicates the land might be polluted, air and soil samples should be taken to find the area of influence. When it specifically comes to methane mitigation, oil fields should be properly capped underground. (Property developers considering sites in the Los Angeles Basin should be particularly aware that the area has the most productive oil fields in California That in turn means that developers must be cognizant of the complexities and impediments of building in this region.) If toxic materials are found on a site or they are migrating from adjacent properties — and the developer still wants to build — a cleanup plan will need to be devised with federal and state regulatory oversight. Depending on how large the area is and the type of project, construction costs and schedules could be impacted in various ways. Hospitals and schools, for example, will have additional oversight agencies such as OSHPD and DSA. Construction delays for cleanups can entail significant losses in time and in capital. Such delays may run at least six months or longer, while mitigation and cleanup expenses can add 10 percent or more to a project's cost. Clearly, building on land that is not vacant, clean or green takes a certain level of care and dollars. Sizing Up Seismic Issues

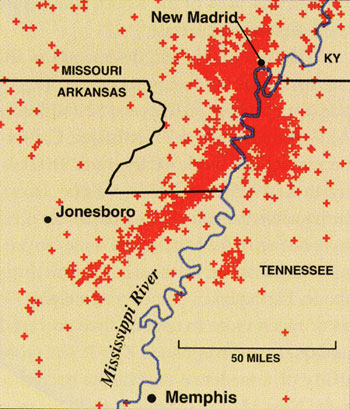

Where Does the Greatest Fault Lie? The greatest earthquake risk east of the Rocky Mountains exists along the New Madrid fault system (pictured in the map above), which runs for 150 miles (242 kilometers), touching parts of six states and crossing the Mississippi River in at least three places.

Map: U.S. Geological Survey, Earthquake Hazards Program In fact, if their historic founders had known about the presence of seismic fault lines, they arguably may have never built some of our greatest cities: Mexico City, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Tokyo. And even today, despite a raft of technological innovations, we are still discovering new underground seismic faults that are not recognized by the U.S. Geological Survey. Geotechnical investigations, however, only identify the presence of known faults. So there is still a possibility that a new fault line can be uncovered during the construction process. A simple rolling hill in the center of Hollywood, Calif., is an example of such an earthquake fault. But since that fault line receives little attention, development activity continues in that area of the city. In other parts of the United States, the population may be tempted to feel immune to earthquakes. Fault lines, however, do exist outside the West. The New Madrid Fault in Missouri, for example, has generated the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the United States. Not only that, but the region that the New Madrid Fault runs through has more earthquakes than any other part of the U.S. east of the Rocky Mountains. Building around Archaeological Finds Archaeological finds, for example, have complicated the 1,087-acre (435-hectare) Playa Vista development, located adjacent to the Ballona Wetlands near Marina del Rey, Calif. The start-up of construction on Phase I of the Playa Vista project unearthed a large Native American burial ground. Construction halted while archaeologists and tribal representatives were brought on site to collect remains and artifacts for possible relocation. Then the EIR for Phase II of the Playa Vista project did not address an already discovered Native American burial area. Consequently, litigation is pending involving Phase II Playa Vista construction.

Water There, Site Selector Beware: Water on a site is one sign that indicates that property development should proceed with caution. Pictured is Balboa Creek inside the Playa Vista development, which lies adjacent to the Ballona Wetlands near Marina del Rey, Calif. A large Native American burial ground was unearthed during the start-up of Playa Vista's Phase I construction.

Photo: Downtowngal Archaeological artifacts also emerged as a significant factor in 2007 when the city of Los Angeles was constructing a new police facility in the North San Fernando Valley at the base of the Los Angeles Reservoir. In that case, however, Indian artifacts and fire pits in areas adjacent to a natural water source had already been discovered before construction began. The earlier discovery prompted the construction crew to use greater care in excavating the project site. Water on a property is one sign that indicates that development should proceed with caution. At sites on or near a location where a body of water once existed, there is a high potential for the presence of archaeological remains. Failure to detect such remains before starting construction carries a steep price. Judges who are especially sympathetic to preservation groups may put a stay on construction that lasts for years, resulting in millions of dollars in litigation costs and delays. Such construction delays may also necessitate building code upgrades if enough time has elapsed between the project's stop and restart. Preserving Eco-Systems

Little Creatures, Big Problems: These two endangered species, the Mission Blue Butterfly and the California red-legged frog, were present on the site in San Bruno, Calif., that officials chose for the San Francisco Jail. Butterfly photo: California Academy of Sciences Frog photo: Chris Brown, U.S Geological Survey For example, native eco-systems played a major — and very expensive — role in the development of the site of the San Francisco Jail in San Bruno, Calif. In that project, the Army Corp of Engineers (ACOE) had completed an EIR that outlined the ecological issues involved at the site. The ACOE designated the project location as the nesting grounds for the Mission Blue Butterfly, which in 1976 received federal protection as an endangered species. In addition, the endangered California red-legged frog inhabited the area. The development of the San Bruno site, however, failed to protect the area adequately. Construction activities in building the new jail destroyed both the plant material and breeding ponds needed to maintain the area's ecological balance. That in turn created financial issues that had not been originally anticipated during the San Francisco Jail's site-selection process. The project's architects and planners were only able to remedy the situation at considerable expense, adding the construction of a series of seasonal ponds and the planting of seedlings. Such missteps, however, have become much more uncommon. Thanks to the sustainability movement of the last decade, many developers have become more sensitive to ecological challenges, and they are more willing to work around them. A good example of that sensitivity emerged in the construction of a new LAPD Bomb Squad Facility in Granada Hills, located in the San Fernando Valley region. To re-vegetate the area, the project team took action before construction began, extracting natural seeds from the indigenous plant material. The area was thus successfully re-vegetated without adding any extra cost to the project. That proactive step helped the Valley Bomb Squad facility to open in January of 2008.

Advance Planning for Advanced Planting: The project team building the LAPD Bomb Squad Facility in Granada Hills took advance action to re-vegetate the area. Before construction began, they extracted natural seeds from indigenous plants, simplifying the re-vegetation process (pictured above). Photo: WWCOT Architects

Conclusion: An Ounce of Prevention . . . To sort through all those issues and find the optimal site, developers should ask themselves hard questions like these:

As always, there are the skeptics who believe that testing is unnecessary and only adds costly delays in the construction process. It is this very lack of awareness, however, that ultimately results in delays, cost overruns and expensive litigation. Chances are, if you're looking out the window of a downtown high-rise right now, those unpleasant scenarios are ones that you will want to avoid when your competitors start building again.

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

|

||||