Supply chain resiliency has become a primary factor influencing site selection decisions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and continued geopolitical uncertainty. Companies perceive supply chain risks differently, but a detailed assessment of port infrastructure — including the resiliency of port services — has become critical to manufacturing site selections.

Determining the resiliency of a country’s port infrastructure by relying on publicly available data is, however, challenging. The variety of terminals, often managed by different operators, within each port makes comparisons difficult, particularly when evaluating non-containerized or non-standard cargo. Data and conclusions offered in these indices can be misleading or even contradictory.

The World Bank’s Global 2023 Logistics Performance Index (LPI), of which ports are a key dimension, ranks Vietnam No. 43 and Thailand No. 34, behind Malaysia (No. 26) and Singapore (No. 1) in Southeast Asia. The LPI scores Thailand above Vietnam by every measure, but the Bank’s Global Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) provides a different assessment. In the 2022 CPPI, Vietnam’s Cai Mep port outperformed its peers in Southeast Asia, including Singapore, with the sole exception of Malaysia’s Tanjung Pelapas, with a ranking just outside the Top 10 globally.

Investor Appetite: Project Experience that Informed the Port Evaluation

In a recent site selection project, Tractus assessed port infrastructure throughout Asia to determine the ability of the region’s ports to meet the requirements of large-scale imports of bulk cargo and exports of containerized cargo. While capacity was a factor, evaluating the port’s resiliency for future operations required assessing other criteria for which data are not readily available. This included terminal utilization and excess capacity, the availability of specialized near-port offloading capabilities, and unloading times for high-volume quantities of dry bulk cargo and medium-volume quantities of container cargo. As the project progressed, Thailand and Vietnam became the focus of the analysis.

Vietnam’s Port Capabilities – Exceeding Expectations

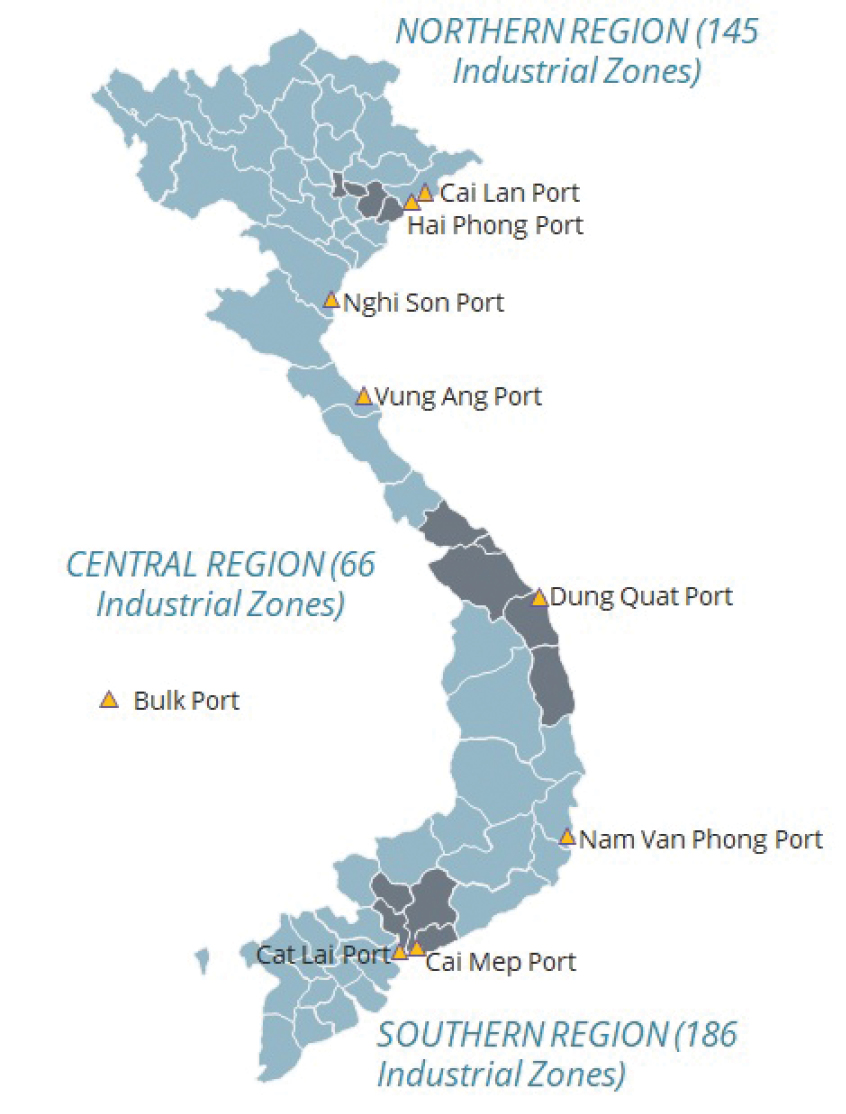

There are eight deep seaports in Vietnam that provide container and bulk cargo handling capabilities. These are located within the principal industrial regions of Northern, Central and Southern Vietnam. However, due to factors influencing the site selection project, our assessment centered on the Cai Mep port complex in southern Vietnam.

Cai Mep port is located in Ba Ria-Vung Tau province in Southern Vietnam. While Cat Lai port in central Ho Chi Minh City is better known, Cai Mep is rapidly evolving as the future of South Vietnam’s sea freight infrastrucutre. The port is a complex of 24 private and public terminals, managed by Vietnamese and foreign operators. Cai Mep can handle 26.5 million metric tons (MT) of bulk cargo and 8.3 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) annually. Like other ports, it has private terminals that cannot be used by third parties. Cai Mep’s principal public terminals include Thi Vai International Bulk Terminal, the Tan Cang Cai Mep Container International Terminal (TCIT), and the Cai Mep International Container Port (CMIT).

Evaluating Cai Mep’s bulk handling capacity and capabilities requires another layer of assesment because in addition to the established terminals along the coast of the Thi Vai River, there are also more than 10 mooring buoys that can be used to significantly expand both dry bulk and container handling capacity. On average, each of Cai Mep’s in-channel mooring buoys can accommodate vessels of up to 70,000 deadweight tons (DWT) and handle over 2 million MT annually.

Thailand Port Capabilities – Specialized and Fragmented Capacity

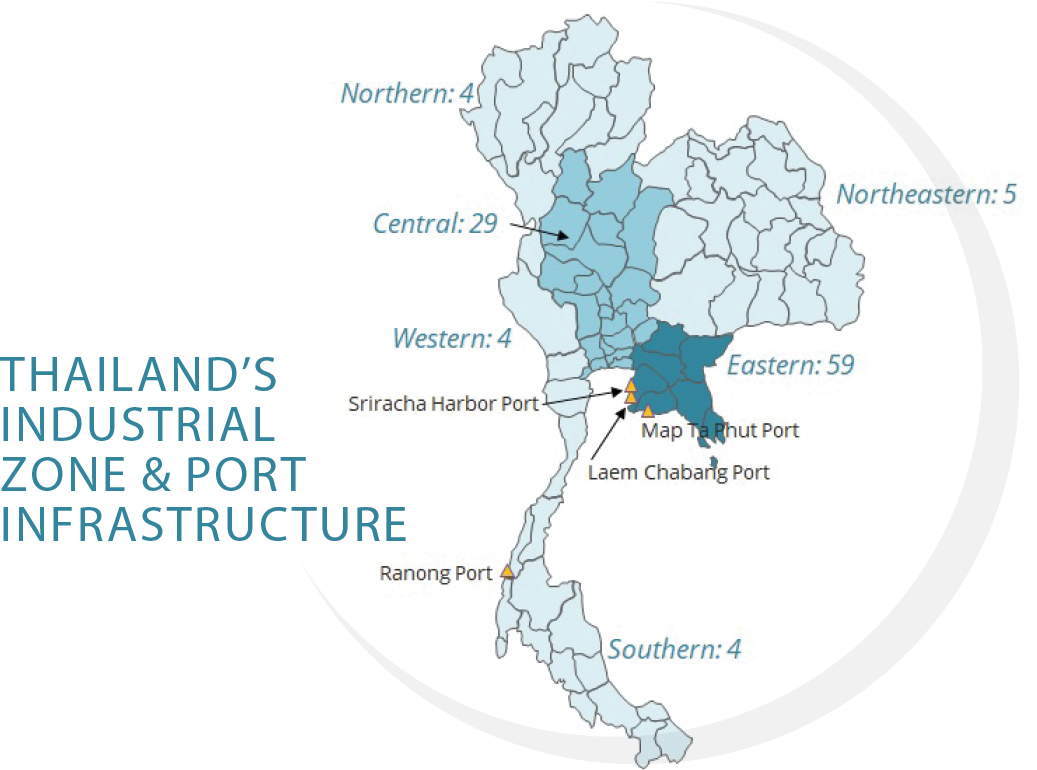

Seaport infrastructure in Thailand is concentrated around Bangkok and in what is known as the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). The EEC comprises three highly industrialized provinces to the east of Bangkok where Thailand’s three deep seaports — Laem Chabang, Maptaphut and Sriracha — are located. Thailand’s deep seaports are more specialized compared to Vietnam. Laem Chabang is the primary container port, and while there is bulk capacity, those terminals are privately operated. The vast majority of internationally traded bulk cargo is handled through Sriracha and Maptaphut ports.

The Laem Chabang port complex includes 13 terminals with an annual capacity of 11 million TEUs. The current utilization rate is 80% and the port is being expanded to accommodate 18 million TEUs annually. Thailand’s principal dry bulk ports — Sriracha port in Chonburi and Maptaphut port in Rayong Province — are both within the EEC and seperated by a distance of 75 km. (47 miles). Sriracha, a privately managed port, has more advanced infrastructure and available capacity, with six berths that can handle 4.5 million MT of dry bulk cargo comapred to Maptaphut’s three berths that can handle 1.2 million MT.

Mitigating Seaport Risks Requires Analysis of Terminal Capabilities

Secondary data provide an indication of the port capabilities and capacity. However, a more in-depth analysis and evaluation of individual terminals and operators is needed to properly assess the ability to mitigate risk.

Vietnam’s Cai Mep port has a scale of bulk handling capacity that Thailand’s two ports cannot match. At 26 milllion MTs, Cai Mep greatly surpasses the combined 6.5 million MTs available in Sriracha and Maptaphut. Laem Chabang has greater container handling capacity at 11 million TEUs, but the terminals in Cai Mep provided a higher combined excess capacity at 1 million TEUs.

Higher throughput provides assurances that the ports have the infrastructure to accommodate high volumes of bulk and container cargo, and this was reinforced when assessing the terminals within the ports. The three separate terminals in Cai Mep provide excess capacity of 4 million MT, significantly higher than the Sriracha and Maptaphut with a combined excess capacity of 2.4 million MT. While the facilities across all terminals in Thailand and Vietnam are professionally managed, Maptaphut currently has limited near-dock warehousing, cranes and services, which are provided in Sriracha and Cai Mep.

Risk mitigation requires options, and the scale of the Cai Mep port complex provides greater flexibility than ports in Thailand. Each of the terminals assessed in Cai Mep could be used to facilitate imports if congestion limited a terminal. The mooring buoys in Cai Mep provide an additional option at a lower costs for unloading than onshore terminals. Maptaphut’s limited capabilities to serve drybulk with cranes and warehousing also reduce the number of options in Thailand, making Vietnam the more resilient location.

In terms of container cargo, Laem Chabang and Cai Mep are comparable. Laem Chabang provides higher throughput volumes at a 79% utilization, while Cai Mep provides two options at respective utilization rates of 87% and 69%. Both complexes provide sufficient services for most large-scale manufacturers, but ultimately the optionality presented in Cai Mep provides greater resiliency.

Southern Vietnam’s port infrastructure demonstrates greater resiliency than Thailand’s with more seaports able to handle larger vessels, a larger number of public terminals, and as good if not better overall port infrastructure for large-scale import and export manufacturing. Moreover, plans for expansion in Cai Mep by an additional 594 hectares, encompassing new container, liquid and dry bulk capacity, by 2040 will provide further assurance for current and future investors that Cai Mep can be relied on to mitigate manufacturing supply chain risks.

Dennis Meseroll is executive director, James Meisenheimer is consulting manager and Sarah Urtz is a senior research analyst at Tractus Asia Ltd., (www.tractus-asia.com), a leading Asia-based global site selection firm.