Since Jan. 2011, Site Selection has tracked company or joint venture projects from The Linde Group (whose head office in Munich is pictured) in Togliatti, Russia; Chongqing and Shandong, China; LaPorte, Texas; Decatur and Wilsonville, Ala.; Lewisville, Ark.; Cilegon, Indonesia; Muttenz, Switzerland; Pasir Gudang, Malaysia; Map Ta Phut, Thailand; Sapugaskanda, Sri Lanka; Balamban, Philippines; and Inju, South Korea.

Photo courtesy of Linde Group

An astounding 1,850 projects across nearly all categories of plastics and chemicals have been recorded in Site Selection’s New Plant Database over the two and a half years since Jan. 1, 2011.

Where they’re going, and why, are topics on the minds of folks at the Society for Plastics Industry and global business analytics and information firm IHS, which in November will co-present the inaugural Global Plastics Summit in Chicago. Among the drivers in the US and elsewhere is abundant and affordable natural gas, much of it attributable to the application of fracking technology out in the field.

While fracking gets the headlines, farming also is driving some of the major investment: As documented in these pages, fertilizer plants are a crop unto themselves, with a number of projects taking place in Louisiana, Iowa and North Dakota. A $1.2-billion fertilizer plant from Cronus Chemical is pending as we go to press, with Illinois and Iowa vying for the project. A decision is expected by the fall on what the Associated Press reports is one of 20 active fertilizer plant location or expansion projects.

Chris Geisler is managing director – Americas Chemical Consulting at IHS Chemical Consulting. He says the current revitalization in the sector after years of decline in the US is due to affordable “backbone feedstocks,” namely natural gas and natural gas liquids such as ethane and propane.

“The overall development of shale gas within the US and all of the infrastructure to separate the natural gas from shale plays has resulted in low-cost natural gas for consumers, and natural gas liquid feedstocks for chemicals as well as residential and fuel,” he says. The cost of feedstocks is the No. 1 strategic driver for plastics and chemicals, he says, typically accounting for more than 70 percent of the overall manufacturing cost of a commodity chemical.

So how strong is the momentum?

“We think shale gas-driven chemical investment by 2030 will exceed $100 billion of new capital,” says Geisler.

A recent IHS report said unconventional gas production in the US – shale, plus “tight gas” – is expected to increase 22 percent to nearly 42 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in 2015 (65 percent of total U.S. gas production) and reach more than 76 Bcf/d in 2035 (75 percent of total U.S. gas production).

The study also projected that the entire upstream unconventional oil & gas sector would support more than 1.7 million jobs in 2012 at average wage levels ($35.15 per hour) dramatically higher than the general economy, with that total expected to more than double by 2035.

That too could benefit the plastics and chemicals sector, as some of its end products serve the oil & gas companies whose own products are proving so beneficial to the plastics and chemicals firms downstream.

“The feedstocks that go into the chemical industry that come from shale gas development go into certain chemicals that are then turned around and used by the oil & gas production industry,” notes Geisler, “things like oilfield chemicals that go into formulations that help stimulate the fields and generate the gas production. Other chemicals go into coatings used to cover pipelines and prevent corrosion.”

Down to Particulars

Depending on the particular chemical or plastic being produced, there are different site selection criteria.

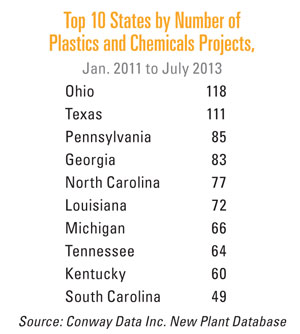

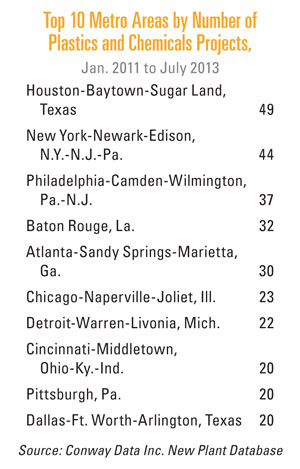

“For the large plants, like methanol and ammonia and ethylene, one of the biggest site selection criteria would be the pipeline grid for either the feedstock or the product,” says Geisler. “Having close proximity to a shared pipeline for the industry is typically a very important thing. That’s why quite a bit of the development has been in the Texas and Louisiana corridors, because there are well-established natural gas, ethane and propane feedstock grids, as well as ammonia and ethylene and propylene pipelines.”

Witness the late July announcement of a joint venture between INEOS Olefins and Polymer USA and South Africa’s Sasol to manufacture high-density polyethylene. The final location has yet to be determined, says INEOS spokesman Charles Saunders. But the two partners already have substantial footprints in the region: Sasol in Lake Charles La., and INEOS in LaPorte, Texas.

Chris Geisler, managing director – Americas Chemical Consulting, IHS Chemical Consulting

Dow Chemical this spring announced it was moving forward with a family of specialty material production unit projects “aligned to its high value Performance Plastics franchise on the US Gulf Coast.” Over the next five to seven years, Dow estimates that these projects, together with all other planned projects previously announced as part of the Company’s comprehensive US Gulf Coast investment plan, will employ approximately 5,000 workers during peak construction and support over 35,000 jobs in the broader U.S. economy.

Still Takes Time

Beyond the feedstock pipeline grid, and the ability to swap and share inventories and supplies of product, there is salt dome storage in the Gulf, says Geisler, “so those interconnections of the industry are very strong drivers for location.”

So is environmental permitting. He notes that Houston is a non-attainment area, but continues to attract projects because that negative is defeated by all the area’s positives, such as incentives, port access and other transport infrastructure. That said, getting emissions permits can take over a year, even in the industry-friendly zone.

“The cost of obtaining certain small blocks of air emission credits to satisfy permit requirements has been in the range of $100,000 to 200,000 per ton and in some cases higher recently in the Houston area, an EPA-designated non-attainment zone,” he says. “The availability and amount of trade of credits is limited, and most existing producers in the area are able to offset new project and expansion project emissions with reductions from other emission-reduction projects in their facilities within the non-attainment area.”

Geisler notes that while some companies are benefiting from using portions of existing sites that might have been mothballed when gas prices were high, the industry’s current appetite for growth means the cost for obtaining the necessary technical and construction work force has gone up.

The Path of Plastics

For plastics, proximity to the feedstock unit is essential, says Geisler, and Texas and Louisiana therefore continue to benefit, thanks to access to rail and to major Interstates, which allow the industry to ship efficiently to the next stage of the industry: converters.

“A lot of that is in the Upper Midwest and Northeast,” he says. “In some cases, depending on the project, it may be in the Southeast.”

One exception for the first stage is the pending Shell ethylene complex in Monaca, Pa., which benefits from being close to the Marcellus Shale, directly on the Ohio River, and connected by quick rail access to converters in the region. It’s part of a wave of 11 million tons of ethylene capacity announced for the US over the next five to six years. The Marcellus may also drive a rejuvenation of petrochemical activity in Sarnia, Ontario, says Geisler.

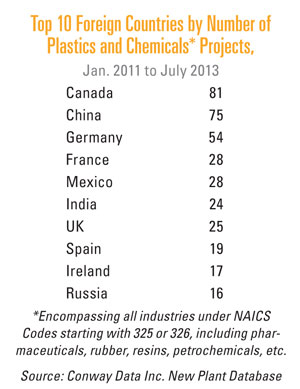

Globally, investment in China continues, Geisler says, driven by market access and low labor costs (even as some pay rates rise). Though there’s some slowdown in the Middle East because of geopolitical turmoil, expansion is still expected there, driven again by low-cost feedstocks. The feedstock price advantage, reports Platts, is driving a number of firms in the sector to downsize HDPE production in Europe. Geisler says Europe is under a lot of pressure because of its inherent cost base, in addition to the solvency issues of various nations. That said, Germany’s specialty and conversion market (particularly for the automotive sector) continues to perform, and Eastern Europe’s lower labor costs are favorable for the conversion industry.

As for Latin America, he notes the growth in Brazil, but there is also growing concern about the competitiveness of the Brazilian chemical industry. Meanwhile, active front-end work is ongoing for new facilities in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

But hovering over all of that activity is the increased interest in the US, often from large Asian and Middle East firms.

“I’ve been in the industry for nearly 25 years, and it’s really something that in the US we haven’t seen in my career,” he says. “It’s a very exciting time for the industry.”