Overlay a map of the Empire State’s vast reserves of higher education and institutional firepower with a map of corporate and industrial R&D, and chances are you’ll see two things: a legacy of innovation, and an interwoven network ripe with opportunities for more.

Zoom in on Erwin, N.Y., just west of the City of Corning. There you’ll find Corning Inc.’s signature research campus, Sullivan Park Research and Development, where Corning is in the midst of a US$400-million expansion.

“The work involves construction of a new facility and renovation of an existing building in the R&D campus,” explains G. Thomas Tranter Jr., president of Corning Enterprises, Corning Inc.’s community and economic development subsidiary. “Work began in 2007 and is expected to be complete in 2013. Some 300 new jobs — mostly science and technology — are being added.”

In the last five years, Corning has invested approximately $900 million and created more than 1,000 jobs in New York, says Tranter, including a diesel filter manufacturing plant that opened in Erwin in 2004 with an investment of $180 million and has since expanded to meet demand both domestically and overseas. “To date, the total investment has been $400 million, resulting in 650 jobs,” says Tranter. “Corning recently invested $30 million to renovate a former photonic technologies manufacturing building for a dual purpose. The facility, which now houses over 500 employees, including approximately 100 new workers, is used as Corning’s IT headquarters and for glass finishing development and pilot manufacturing for projects emerging from Sullivan Park.”

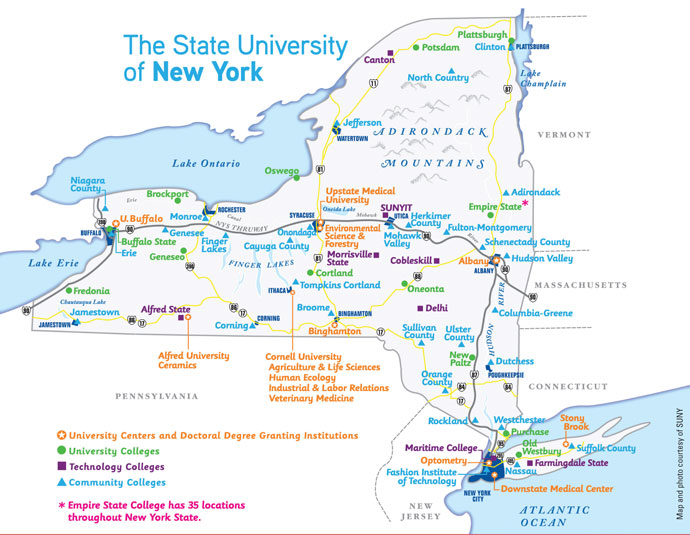

The higher education profile of New York — including the 64 campuses and 467,000 students of the State University of New York system — adds indisputable heft to the already substantial R&D investments in the state by such global organizations as Corning, General Electric, IBM, semiconductor consortium International SEMATECH and others.

Tranter says collaborative research sponsored by Corning at public and private universities in New York not only helps further knowledge in particular fields, but often can result in “Corning identifying talented doctorate candidates and post-doctoral researchers who in many cases join Corning upon the conclusion of their academic studies.”

That kind of give-and-take investment is one way Corning and others deftly blend internal and external resources to control costs in such areas as energy use and taxation. In Corning’s case, an internal Global Energy Management program launched in 2005 has coalesced with external work with local industrial development agencies to secure available tax abatements for projects that create and/or retain jobs. “Also, Corning has supported legislation such as the Recharge New York program which allocates discount power to companies across the state as an incentive to keep companies and jobs in the state,” says Tranter.

Such programs are in keeping with a pronounced effort on the part of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Empire State Development to improve the state’s business climate in as many ways a possible. Cuomo has called for increased public-private partnerships; more investment in infrastructure; and a $750-million second round of the well-received New York Regional Economic Development Council grant program he launched last year.

Regional Recharge

Empire State Development President, CEO & Commissioner Kenneth Adams says the 10 regional councils “really have helped to highlight across the state the connection between top-shelf higher education institutions and the economy,” whether it’s the multiple schools that are members of the New York State Smart Grid Consortium or the University at Buffalo’s focus on life sciences, biotech and medical devices. “A college or university president is always a co-chair,” he says of the regional councils. SUNY campuses received 24 awards totaling $40 million out of the $785 million in grants from that program’s first round.

Taken as a whole, Adams says, the layering of private schools, the SUNY system and research institutions across the state provides “a powerful foundation for innovation that I’d argue no other state has.”

In a sense, that foundation mirrors the geographic layout of the state’s famous rail and canal industrial infrastructure. Adams says that’s no accident, and the generations of families that have driven Upstate New York’s manufacturing prowess are poised to drive its high-tech leadership as well, he says, pointing to Rochester, where the now-bankrupt Eastman Kodak for years provided the backbone for the development of the area’s highly skilled, technically adept work force.

“The next generation of high-tech manufacturing in Rochester is not going to be a surprise to anybody,” he says.

Tranter says Corning, a world leader in specialty glass and ceramics, “has existed for more than 160 years largely because of its vibrant innovation heritage,” from developing the glass envelope to commercialize Thomas Edison’s electric light bulb, to cathode ray tubes, to ultra-slim bendable glass for electronic devices. “Employees at our research and development center, located near our global headquarters in Corning, N.Y., leverage our core competencies and expertise across technologies and businesses to solve complex problems to meet current and anticipated global market needs. “

With that sort of critical mass assembled, has the company ever seriously considered moving its headquarters elsewhere?

“No,” says Tranter.

Global Manufacturing Leader

Celebrates 40 Years on Long Island

Germany-based Festo, a process automation and pneumatic controls technology company, could be said to be at the birth of its third generation of high-tech manufacturing, as earlier this year its U.S. division celebrated 40 years of doing business on Long Island.

Frank Langro, director of marketing and product management for Festo USA, says the company got its start in nearby Port Washington in Nassau in 1972, supplying spare parts for equipment imported from Germany. But over the years the company saw the opportunity to build packaging equipment and machine tools right in the U.S. for its customers. The company outgrew its original facility and moved to Hauppauge in 1981.

Over the past two years it’s added 125 employees to the payroll, invested in facility improvements and established design, engineering and manufacturing capacity, a regional HQ for all of the Americas, and a logistics and support hub for NAFTA.

“A lot of people find it surprising that we do manufacturing, design and engineering on Long Island, because of costs and the perception of costs,” he says. But engineering has only become more important as the years have passed.

So has education. Festo operates a learning division it calls Didactic, which provides vendor-neutral training for its industrial customers on pneumatics, PLCs and other technologies.

In some ways it seeks to fill the knowledge gap on the factory floor that in Europe is filled by more powerful apprenticeship programs. The company also sponsors robotics competitions and other programs at the K-12 level.

Langro says the focus is on the overall work force, via partnerships with community colleges and technical schools that use hardware to simulate a factory floor. Farmingdale State College has been a key partner for years, as have Hofstra, Suffolk Community College and SUNY-Stony Brook.

“We have a couple interns right now from Stony Brook in our engineering department,” says Langro, and the company has reached out to Hofstra and Suffolk about internships as well.

“Internships open eyes to the fact that there is talent here on Long Island that can be cultivated,” says Langro, “and that there are opportunities here” for graduates.

Festo has considered moving before, but has always chosen to stay home, in part because of steady communication with state leaders about such issues as energy and transportation, and what changes have been needed to keep the company in state.

“There is clearly an effort, and it’s appreciated,” says Langro.

But he’d like to see even more collaboration from institutions such as SUNY, and is especially keen on expanding co-op programs whereby students can earn credits by working at a company.

A System Opens Its Doors

As it happens, SUNY is in the midst of an unprecedented commitment to bringing co-op education to scale via its SUNY Works program. SUNY Chancellor Nancy Zimpher hears from Long Island businesses regularly, and knows that such programs are hitting a sweet spot. She also cites training and preparation opportunities such as the six-institution nano consortium, and the turbine engineering training offered at Clinton Community College in Clinton County.

“We’re training aviation technicians because Laurentian Aerospace recently moved into the North Country and is going to hire 900 technicians. When I was visiting, they had just cleaned out the training space for wind turbine technologies, and were creating a six-week workshop for aviation technology. They’re much more nimble, and can turn around curriculum on a dime for any industry locating in a community.”

Zimpher has just recommended National Science Foundation leader Tim Killeen for the dual post of president of the SUNY Research Foundation and SUNY vice chancellor for research. “I am confident his leadership will allow us to maximize the power of SUNY research across New York State,” she said in May.

The new post comes after what Zimpher calls “a scrub” of the Research Foundation involving the implementation of 50 recommendations from an external consultant. Asked how she’d grade her own system in terms of openness and flexibility with industry partners when it comes to IP, licensing and related matters, she says, “I give us an ‘A’ for infrastructure, but what we weren’t doing was creating policy. Now we can more quickly and effectively move discovery and co-discovery to the marketplace.”

Zimpher’s approach is based on “systemness,” which she defines as “the coordination of multiple components that when working together create a network of activity that is more powerful than any action of individual parts on their own.”

Sounds a lot like the project and facility portfolio of a typical multinational corporation. Preston Gilbert, operations director for the SUNY Center for Brownfield Studies in Syracuse, can relate, coming as he did from the world of economic development to the world of academia. He cites the busy hive of activity in his city, as well as fiberoptics in Rochester and Cornell’s big plans in New York City.

“There is a lot happening,” he says. “Despite Upstate lagging economically, the blessing is we’re a relatively diverse economy in New York. The state coming forward with these various programs really puts us in a very attractive position to use these incredible physical and university assets we have. And there’s this huge wealth of expertise in other private institutions in the state.”

Yes, he says, the regional council grant program is a competition, but the available intellectual resource is deep, wide and abundant, whether you’re a community searching for a project or a project searching for a community: “It’s a rich pool to fish from.”