E-commerce and logistics stand out in the pandemic-struck global economy: Companies are not only working 24/7 to deliver goods to stuck-at-home shoppers, they’re hiring by the tens of thousands while they’re at it. Amazon made two hiring pledges this spring that totaled 175,000 jobs, and has continued opening fulfillment centers in places such as Hampton Roads, Virginia, and New Castle, Delaware. Dollar Tree, despite seeing its store-opening plans slowed by the coronavirus, still pledged in May to hire 25,000 Dollar Tree and Family Dollar distribution center and store employees across its network of 15,000 stores and 24 distribution centers — with more centers on the way.

Pandemic Vaccine Delivery: What’s the Plan?

But there’s one logistics question on everyone’s mind. When a vaccine comes along, how will it get to everyone equitably?

I asked several pharmaceutical companies on the vaccine development front lines to describe the logistical and ethical protocols they have in place when it comes to equitable global distribution of treatments and vaccines. One responded.

“In partnership with BioNTech, we have expedited our traditional timelines to develop a vaccine against COVID-19,” explained Sharon J. Castillo, senior director, Pfizer media relations. Pfizer is one of five organizations — along with AstraZeneca/Oxford, Johnson & Johnson, Merck and Moderna — chosen by the Trump administration to receive additional government funding and clinical trial support for their novel coronavirus vaccine candidates, in addition to financial and logistical assistance for scaling up manufacturing.

“Clinical trials are now under way both in Europe and the United States for four different mRNA vaccine candidates,” said Castillo. “We believe that the approach we are taking has the potential to deliver a safe and effective vaccine candidate against COVID-19. If all goes as expected during our clinical work, we hope to be able to produce millions of vaccines by the end of 2020, and hundreds of millions of vaccines by 2021.”

As for delivery, “In parallel with production, we will collaborate closely with regulatory and health authorities around the world to provide a potential vaccine to areas in greatest need, based on patient demographic data being produced in real time and being monitored throughout our clinical development process,” she says.

Cold, Cold, Cold

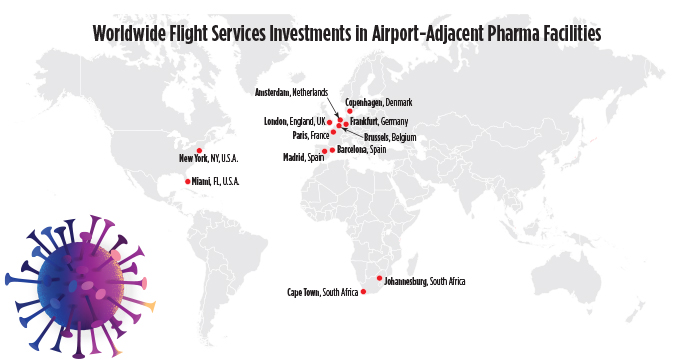

Delivery at large scale requires specialized delivery methods and a solid network of cold chain storage. That’s an area receiving ample investment. Paris-based Worldwide Flight Services’ recent multi-million-euro investment in 12 dedicated pharma facilities at airports in Europe, the U.S. and Africa “generated significant increases in time- and temperature-sensitive volumes in the first five months of 2020,” said the company in June, “and will provide vital support to airlines, freight forwarders and their health care customers involved in the global distribution of a coronavirus vaccine once one becomes available.

Cold storage demand for food has also increased dramatically. A spring report from CBRE suggested that an additional 75 million to 100 million sq. ft. of industrial freezer/cooler space will be needed to meet the demand generated by online grocery sales in the next five years in the U.S. alone. Those spaces will be serving restaurant, grocery and consumer needs alike, and feature more automation. A later report in May noted that businesses may create more domestic supply chains as they re-shore or near-shore production.

“According to CBRE Research, a 5% increase in business inventories requires an additional 400 million to 500 million sq. ft. of warehouse space,” said CBRE, cold or not. “Markets with convenient access to seaports may offer very limited space options. This likely will benefit inland hub markets,” including the Inland Empire and Central Valley of California; Atlanta; Pennsylvania’s I-78/81 corridor; Memphis; Florida’s I-4 corridor; and the upstate South Carolina market around Greenville-Spartanburg.

Essential and Critical

With an economic impact of approximately $84 billion on north Texas, the 26,000-acre master-planned community and global logistics hub AllianceTexas is home to plenty of logistics centers. Its assets were considered essential businesses and critical infrastructure as the COVID-19 pandemic struck the U.S. That’s why Mike Berry, president of Alliance developer Hillwood, a Perot Company, could be found in his team’s triple-cleaned and mass-fumigated office this spring as part of a designated “SWAT” team strategically spread across the office as 85% of their colleagues worked from home.

“The Alliance platform is largely built on logistics, e-commerce and supply chain, so we have a huge responsibility to keep everything working on that front,” he told me. “All of those businesses we’re in fall under the definition of critical and essential.”

Many service workers who have lost their jobs probably won’t find those jobs again. But logistics and supply chain will generate a demand for more people.”

One could argue such operations are worthy of that designation at any time. But never more so than during a global crisis. Maybe that’s one reason Hillwood Chairman Ross Perot, Jr., serves on both President Trump’s and Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s economic recovery committees. Berry said customers such as Amazon, FedEx, BNSF and UPS, as well as major grocery and consumer goods distributors, were completely functional and in many cases “working overtime, humping it to keep up with inventory replenishment.”

Stocking those companies’ workforces was therefore paramount too, as several quickly ramped up hiring as the health crisis spread. Hillwood already pioneered workforce certification and training programs years ago for its tenants, and recently hosted the opening of the Tarrant County College Center of Excellence in Aviation, Transportation and Logistics.

Now, says Berry, “We’re building a software platform using a company called ShiftSmart, and making it available to employers in order to shift and match available labor with hourly jobs in busy fulfillment and logistics centers all over AllianceTexas.

“We are going to learn a lot from this experience. In particular you’ll see a real need to shift a lot of the labor long term. Many service workers who have lost their jobs probably won’t find those jobs again. But logistics and supply chain will generate a demand for more people. There’s an opportunity for us to really build a labor shifting platform where we can allow people to learn new skills and get places in the logistics industry, as a result of what we’ve seen in the last 90 days.”

The new AllianceTexas Mobility Innovation Zone being put into place with Deloitte may offer even more promise in the years ahead, in such areas as freight automation, drone delivery and urban mobility.

With a BNSF intermodal hub that runs 1.5 million containers a day, 3,500 trucks a day and 63,000 employees on site across 50 million sq. ft. of space, says Berry, “If we can knit all those things together with these new technologies and show how they work at large scale, we can help the market accelerate to commercialization.

“We have an amazing opportunity to be a convener and catalyst to help this industry grow and develop, and we can use the Alliance Texas platform to do that,” Berry says. “If it works, we hope to be the home where these devices can be built.”