Chip-Making Subsidies

Spark Semiconductor Downturn?

by JACK LYNE, Site Selection Executive Editor of Interactive Publishing

|

|

| China's future rank as the world's largest chip market has attracted major outside players like Intel, whose CEO, Craig Barrett (pictured at left in the photo at left), came to the west China city of Chengdu earlier this year for the construction start for a new assembly and test factory. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Chairman Morris Chang (pictured right), however, has predicted that China's fast—growing homegrown chip capacity will ultimately trigger a broad semiconductor industry recession next year. | |

BEIJING and SHANGHAI —

To paraphrase Paul Revere: The Chinese chip-makers are coming; the Chinese

chip-makers are coming. And with the aid of China's

rich subsidies, they're moving fast. China's snowballing

growth in domestic chip-making is getting some serious momentum from

the generous incentives coming from the country's all-powerful central

government. And Beijing's subsidies are adding appeal to a country that

has already long been offering low operating costs in key areas like

land and labor.

China's fast-growing homegrown semiconductor

industry — a sector that virtually didn't even exist a few years

ago — is beginning to have a very broad impact. The Asia-Pacific,

after all, is now the world's largest chip market. Moreover, the US$19-billion

Sino semiconductor market by itself ranks as the world's third-largest;

and it's the fastest-growing as well.

China's domestic chip-making is expanding

so furiously, in fact, that it could conceivably spur an industry-wide

semiconductor recession next year, some high-profile observers are warning.

By 2005, in fact, Sino semiconductor production is on pace to provide

20 percent of the entire world's made-to- order chip capacity.

If that huge output stimulates a chip-making recession, it would end

the larger industry's current profit surge — and only three years

after its worst-ever downturn.

In the meantime, China's fetching subsidies

for domestic semiconductor manufacturing are already altering some non-Sino

firms' site-selection moves. Asian projects that were initially ticketed

for established chip meccas like Taiwan have instead wound up locating

on the mainland.

Two major homegrown semiconductor players

— Grace Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp.

www.gsmcthw.com)

and Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp.

(SMIC at www.smics.com)

— particularly demonstrate Sino-based chip-makers' advantages.

Both Shanghai-based firms are very rapidly

increasing their output.

But there's also a counter-trend at play

here: China's preferential aid for its own homegrown chip-makers is

showing signs of erosion. A strong U.S. backlash caused some major Sino

subsidy cutbacks earlier this year in the face of potential World Trade

Organization (WTO at www.wto.org)

sanctions.

Buoys Domestically Based Operations

|

| U.S. Trade Representative Robert B. Zoellick (pictured) earlier this year charged China with "discriminatory tax policy. As a WTO member, China must live up to its WTO obligations; it cannot impose measures that discriminate against U.S. products." |

- 100-percent corporate income tax exemptions for five years, followed by a 50-percent rate for five years at 7.5 percent.

- An effective 3-percent value-added tax (VAT) rate on China—made chips.

Regulations that aid skilled professionals' recruitment are further fueling China's semiconductor growth. Company stock options given to imported chip-making recruits, for example, are doubly lucrative. Those Chinese stocks aren't taxed at market value; but they can be sold without paying any capital-gains taxes.

Moreover, China's government makes substantial direct investments in prominent homegrown chip-makers. Beijing, for example, owns 62 percent of Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. www.asmcs.com) (which was known as Philips Semiconductor Corporation of Shanghai from 1989 until 1995).

|

|

| Well connected men: One of Grace Semiconductor Manufacturing's founders is Jiang Mianheng (pictured left), son of Jiang Zemin, former People's Republic of China president. And Grace's board members include Neil Bush (pictured right), the younger brother of U.S. President George W. Bush. | |

Have Hastened Company's Growth

Such contract companies are getting a major boost from the semiconductor industry's staggering capital-intensiveness. New fabs now cost around $3 billion, and retooling operations for crucial nex-generation products is a huge capital drain as well. For many companies, the more cost-effective solution is outsourcing some chip-making to big Asian foundries that pool multiple semiconductor manufacturers' requirements. Those industry trends, combined with China's support network, have clearly sped Grace's and SMIC's growth. Grace also illustrates another truism in Chinese chip-making: There's no such thing as being too well-connected.

One of the company's two founders, for example, is Jiang Mianheng, son of Jiang Zemin, the former People's Republic of China president. And Grace's other founder is Winston Wang, son of billionaire industrialist Wang Yung-Ching, one of Taiwan's richest men and chairman of Formosa Plastics Corp., the top Taiwanese petrochemical player. Some observers credit Jiang and Wang with raising almost $1 billion for Grace in low-interest Chinese bank loans.

On top of that, one member of the Grace board is Neil Bush, the younger brother of U.S. President George W. Bush (R). Bush was awarded a $2-million-a-year-salary when he was tapped for board membership in 2002. (The quietly arranged appointment became public during Bush's contentious 2003 divorce.) The American brought no chip-industry experience of note to his board role. Grace picked Bush, many observers feel, to try to get the U.S. to ease limits on technology transfer to China

(which hasn't happened).

chip-making.

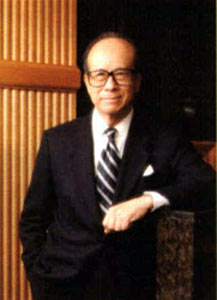

Late last month, Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing, Asia's richest man, announced that he would spend $90 million for a Grace stake.

|

|

| Clout counts: Grace Semiconductor will use a recent $90—million investment by Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka—shing (pictured), Asia's richest man, to expand its Fab 1A in Shanghai and to fund its IPO. |

"We are very excited by this latest investment from the two most accomplished and prestigious companies in Hong Kong today," said Grace President Dong Yeshun. "Given their investment experience in the Chinese telecommunications and information-technology sectors, their expectation that Grace will become one of China's leading semiconductor foundries represents a substantial endorsement of our farsighted business strategies."

The company will use the new capital to increase advanced R&D and expand its Fab 1A in Shanghai's Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park, Dong added. Fab 1A's current monthly output of 25,000 eight-inch wafers will increase to 33,000 in the first half of 2005, Grace is projecting.

The new investment will also help fund Grace's initial public offering, corporate officials said. The firm hopes to raise $700 million to $1 billion with IPO placements in Hong Kong and

the U.S.

That payoff also advances another central value in China's "close followership": absorbing and diffusing foreign technology. The cooperative Sino approach markedly differs from the "leadership model" for industrial development employed in other world regions like the European Union. That strategy essentially treats U.S. industry as a rival, particularly in the technology arena. But China is trying to glean all it can from American technology.

Grace's and SMIC's technological alliances mirror that approach. Both firms, for example, are partnering with Dallas-based Texas Instruments (TI at www.ti.com). SMIC announced in late October that it had signed an agreement with TI to develop process technologies for 90-nanometer chips. Grace says that it plans to enter its own 90-nm. processing agreement with TI next year. The two firms' other alliances similarly focus on absorption and diffusion.

Grace's technological tie-ins, for example, include Toshiba, as well as Silicon Storage Technology, which has invested $50 million in Grace in cooperatively working on embedded-flash technology. SMIC's partnerships range even farther afield, including Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing, Elpida Memory, Fujitsu, Infineon Technologies, IMEC and Toshiba.

|

|

| Growth signs: China's fast—growing homegrown chip industry is reflected in SMIC's eight—inch Tianjin fab (top), originally a Motorola chip plant that the U.S. company last year exchanged for stock in the Chinese firm. More indigenous growth is evident at Grace Semiconductor's Fab 1A in Shanghai (bottom), which will up wafer capacity by a third in 2005's first half. |

Like Grace, SMIC has grown very rapidly, but on an even broader scale. The capacity of China's largest chip-maker now extends well beyond the company's three Shanghai-based fabs, which this year will register a projected 70-percent increase in eight-inch-wafer capacity. SMIC also has added an eight-inch Tianjin fab that was originally a Motorola chip plant. The U.S. company late last year exchanged that facility for SMIC stock. In addition, SMIC will soon open a new 12-inch fab in Beijing, and it has plans to add more new fabs in 2005 and 2006.

One of them is Morris Chang, chairman of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.(www.tsmc.com), the world's largest made-to-order semiconductor-maker. Chang set off alarms inside the chip industry with his speech at the Semiconductor Industry Outlook 2003 conference in San Jose, Calif. Surging Sino chip production, he advised, could well mean a semiconductor industry recession as early as 2005.

That outcome, Chang noted, had strong historic precedents. The glut of China-made chips, he explained, could repeat the recession-triggering overcapacity that came from Japan in the 1980s and South Korea and Taiwan in the 1990s.

"Taiwan has become the dominant foundry country and the second most important design country after the U.S.," said Chang. "China will go on the same journey that Taiwan started 30 years ago." Chang last year reiterated his assessment.

China's VAT Rate Equalization

|

|

| China in late 2001 celebrated (pictured right) its acceptance for membership in the World Trade Organization (whose Geneva headquarters is pictured on the left). That membership, however, eventually triggered the elimination of China's VAT differential, which was in place before joining the global trade group. | |

That policy shift began to take shape on March 18th, when the U.S. filed a WTO complaint against China's unequal VAT rates. That marked the first WTO action against China since it joined global trade's governing body in late 2001. "The United States believes that this discriminatory tax policy is inconsistent with the national treatment obligations that China assumed when it joined the WTO in December 2001," U.S. Trade Representative Robert B. Zoellick said as the American complaint was filed. "As a WTO member, China must live up to its WTO obligations; it cannot impose measures that discriminate against U.S. products."

The VAT agreement came only after extended negotiations between China and the U.S.

"Elimination of the discriminatory features of China's VAT regime will assure a level playing field for

|

| Sino support for homegrown chip-makers includes direct government investments in companies like Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (ASCM) in Shanghai (where a worker is pictured above). Beijing owns 62 percent of ASCM. |

Cheng Ming-kai, for example, a semiconductor-sector analyst with CLSA (www.clsa.com), said in a note to investors, "The impact will be a structural one, as investors will start to realize that the main advantages of producing chip products in China have disappeared. The move will have an obvious impact on the likes of SMIC. [SMIC's] incentive to produce will decline, since the VAT incentives to offset production efficiency differences will disappear." But other observers don't foresee any such outcome.

Contract manufacturers like SMIC, they point out, will likely stay in steady demand, considering how established outsourcing has become for made-to-order chips. The VAT differential's end, those analysts add, won't touch the rest of China's strong financial support for homegrown players. (Many critics of America's chip-making strategy, in fact, want the U.S. to emulate China's support of its indigenous firms.)

As for non-Sino firms, major chip manufacturers like AMD, Intel and NEC will certainly continue to operate their own on-the-Chinese-ground joint-venture fabs and R&D centers. Those operations are essential, such companies believe, to keep a finger on customers' collective pulse inside what's destined to be the world's biggest semiconductor market.

|

| Semiconductor Industry Association President George Scalise (pictured) said that China's VAT equalization "will assure a level playing field for all competitors." |

That line of thinking was underscored by last month's expansion decision by two foreign chip-makers: South Korea's Hynix (www.hynix.com) and Switzerland's STMicroelectronics (www.st.com). The two companies announced on Nov. 15th that they will establish a $375-million joint-venture fab in Wuxi City. Employing 1,500 workers, the plant will make DRAM and NAND flash chips for the Chinese markets, the two companies said.

For U.S. chip-makers, profits will rise with VAT equalization, the SIA is projecting. That payoff, say SIA analysts, follows simply from the fact that U.S. firms control about 50 percent of the world chip market. (China, for example, still imports about 80 percent of its new chips each year.)

As for Sino chip manufacturers, they're still newcomers to the chip-making game. Nonetheless, China's indigenous semiconductor players seemingly have a guaranteed long-term revenue stream in a potent combination: ingrained chip outsourcing, plus the nation's low costs and the government's financial support. And that suggests another certainty: The Chinese chip-makers are coming.

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE

PLEASE

VISIT OUR SPONSOR • CLICK ABOVE