In the legendary musical “Hamilton,” the protagonist sings, “We studied and we fought and we killed for the notion of a nation we now get to build.”

The new Hamilton Index of Advanced-Technology Performance, released in May by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF), measures how well U.S. states are doing at building the economy of tomorrow through production in advanced industries.

Here, with ITIF’s permission, we showcase some of the new report’s findings with particular attention to the manufacturing components of the index. We also speak to report co-author and ITIF Founder and President Robert D. Atkinson about what his team’s findings portend for companies wishing to invest in various regions of the United States.

Selected Key Takeaways from the Hamilton Index:

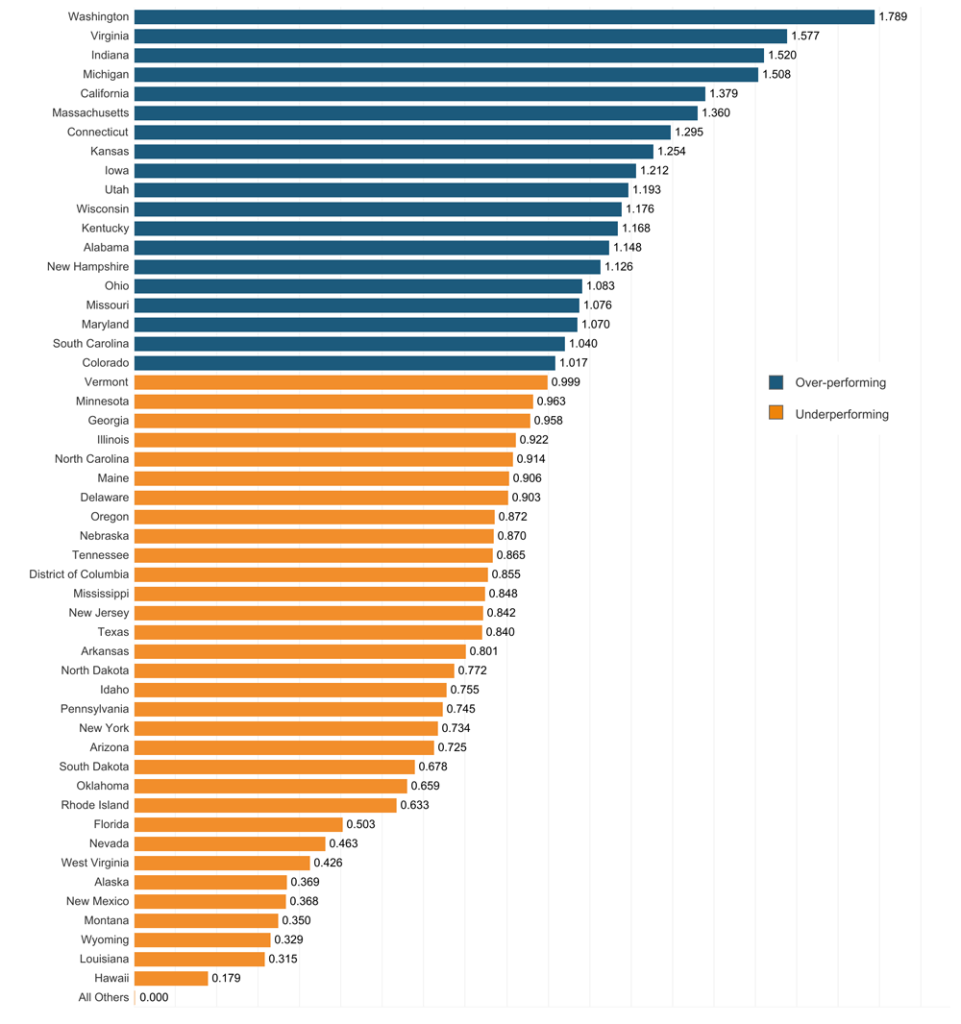

- Washington, Virginia, and Indiana rank highest in the 2025 State Hamilton Index, while Wyoming, Louisiana, and Hawaii are the worst performers.

- Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia underperform in advanced industries. Strengthening these industries nationwide is critical to economic growth and national security, especially in the face of rising competition from China.

- Most advanced industries are geographically concentrated in just a few states (e.g., biotech in Massachusetts and aerospace in Kansas). Targeted growth efforts such as retooled regional technology hubs can reduce national dependence on these states.

- Strengthening America’s advanced industries will require policies that combine federal funding with state-level specialization — such as technology grant programs similar to the CHIPS Act.

- China is more specialized in Hamilton industries than are 98% of U.S. states.

The United States faces fierce competition for global market share in traded-sector, advanced technology industries, wherein success directly impacts national economic strength and security. As China’s economy continues to grow and innovate — surpassing expectations from just a few years ago — the United States must look to expand its innovation and production capacity.

COMPOSITE HAMILTON INDEX LQ

Graph courtesy of ITIF

If the United States wants to grow domestic production, the federal and state governments must coordinate a national industrial strategy in which U.S. states prioritize the development of industries that strengthen the national economy — not just their own.

To assess the industrial performance of U.S. states and the District of Columbia, ITIF examined their share of U.S. output in seven industry sectors, which are aggregated into the Hamilton Index of Advanced-Technology Performance: information technology (IT) and information services; computer, electronic, and optical products; pharmaceuticals and biotechnology; electrical equipment; machinery and equipment; motor vehicles; and other transport equipment. We also compared each state’s total concentration with the globe’s and China’s and used data from the United States Census Bureau’s dataset on total employees in 2022.

The seven industries included in the Hamilton Index together accounted for 8 million workers in the United States in 2022. The IT and information services industry (including software and Internet services) is the largest of the 10, accounting for 48% of all employees in Hamilton Index industries. Using data from the Hamilton Index published in 2023, America’s aggregate performance in advanced industries has been weak over the last two-plus decades, barring the IT and information services industry, which has seen growth due to leading U.S. firms such as Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

To assess states’ relative performance in strategically important industries, ITIF used an analytical statistic known as a location quotient (LQ), which measures any region’s level of industrial specialization relative to a larger geographic unit — in this case, a state relative to the United States as a whole. States with LQs at or above 1.00 are considered over-performing, while all LQs below 1.00 are considered underperforming.

Nineteen states have LQs above 1.00, indicating that they are above the national average in the aggregate output in the 21 Hamilton subindustries analyzed. Washington state ranks first with an LQ of 1.79, driven by its diverse landscape of advanced technology companies, mainly in Seattle, including IT and aerospace firms. States focusing on high-tech industries, such as Virginia, California and Massachusetts, ranked second, fifth, and sixth, respectively. At the same time, manufacturing hubs such as Indiana, Michigan and Kansas were third, fourth and eighth overall, respectively.

The composite rankings revealed both surprising and expected findings. Rural states such Oklahoma (0.66) and Wyoming (0.33) underperformed in the composite score, revealing the dependence on low-tech, agrarian, and service-based industries. At the same time, states with large urban centers, such as Texas (0.84), New York (0.73), and Florida (0.50), were below the national average.

China’s industrial and innovative capabilities, at least in terms of LQ, significantly exceed the United States’. In this position, the United States has placed itself at risk in economic and national security, making itself vulnerable to weakened supply chains, trade manipulation and economic instability.

Piego Connally, assembly team leader, delivers results at General Motors’ Fairfax Assembly plant in Kansas City, Kansas, one of four states (Michigan, New York and Tennessee are the others) slated to receive around $4.9 billion in GM manufacturing investments.

Photo courtesy of GM

Across-the-board tariffs on most countries and industries are not likely to do much to change this, in large part because most advanced industries rely on foreign markets for a considerable portion of sales, and aggressive U.S. trade protection will lead to an equal response from foreign nations, reducing many of these firms’ foreign sales. As such, to reclaim leadership in advanced industries, the United States must adopt a comprehensive, coordinated industrial strategy that aligns federal and state policies toward a common goal: strengthening domestic production in key sectors.

The time for a piecemeal approach to industrial strategy has passed. Without decisive action, the United States risks falling further behind. By leveraging comparative advantages at the state level, fostering innovation clusters and committing to sustained investment in advanced industries, the United States can rebuild its industrial foundation and reassert itself as a dominant force in the global economy.

“A successful hub should, within five to 10 years of designation, evolve into a globally competitive, self-sustaining innovation cluster, no longer dependent on continued federal support.”

— ITIF Founder and President Robert D. Atkinson

A Q&A with Rob Atkinson

How would you advise a multinational corporation or SME to use the Hamilton Index as a site selection tool?

Rob Atkinson: The State Hamilton Index is a valuable tool for companies — both multinational corporations and SMEs — seeking to make informed site selection decisions. Its main purpose is to help firms assess the level of agglomeration economies for their particular industry across different U.S. states. In simple terms, it measures how concentrated an industry is in a given area. Agglomeration refers to the idea that the economic strengths of a region are greater than the sum of its parts. Companies benefit from being located in places like Silicon Valley not just because of proximity to other tech firms, but because of the rich ecosystem: international airports, venture capital, skilled workers, research universities and more.

The same principle holds true for manufacturing economies. For nearly 75 years, American hubs like Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis and Chicago grew because of agglomeration. These regions offered dense supplier networks, a pool of skilled labor, relevant training institutions and specialized infrastructure — all of which allowed industries to flourish and evolve together.

The Hamilton Index captures this dynamic. If a company is in an industry and is considering relocating to a state where that industry is virtually nonexistent, that’s a red flag. Conversely, moving to a state with a critical mass of similar firms provides strategic advantages — access to suppliers, talent, knowledge spillovers and more. The Index doesn’t make decisions for firms, but it offers crucial insight into regional industrial ecosystems that can significantly inform the location strategy.

Your recommendation to reorganize Tech Hubs, NSF Engines, etc. seems to align with what U.S. Commerce Secretary Lutnick has announced will be a streamlining of the Tech Hubs program. Name a few locations you see standing out as the most viable to continue among whichever regional coalitions are selected to continue receiving federal support.

Rob Atkinson: The key issue is whether the administration intends to reorganize the program or cut it. It should not be cut — there was barely enough funding to begin with. In its current state, the program tried to do too much with too little, and some of the regions selected lacked the long-term potential to become self-sustaining innovation hubs.

So, yes, streamlining the program is the right move. A more effective approach would prioritize what we called “Goldilocks regions” — not already dominant innovation centers, but places with the right ingredients to blossom with targeted federal support. Crucially, there was insufficient coordination between the NSF and EDA hubs, resulting in overlap and fragmentation.

A successful hub should, within five to 10 years of designation, evolve into a globally competitive, self-sustaining innovation cluster, no longer dependent on continued federal support. But the reality is that most regions will not reach that point. Only regions with at least moderate existing tech capabilities have a credible chance.

Beyond hard assets, “community capital” is critical — the ability of regional leaders across public, private, academic and nonprofit sectors to collaborate energetically and strategically. If a region can’t align its leadership around a clear innovation vision, it likely won’t succeed, regardless of funding.

The original ITIF report proposing the Tech Hub program listed a number of metrics and potential growth centers.

ITIF’s Top 20 Potential Growth Centers

| Name | Eligibility Index |

| Madison, WI | 1.63 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 0.68 |

| Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY | 0.66 |

| Lexington-Fayette, KY | 0.58 |

| Rochester, NY | 0.53 |

| Provo-Orem, UT | 0.47 |

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 0.47 |

| Tucson, AZ | 0.45 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 0.40 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 0.34 |

| Columbus, OH | 0.30 |

| Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI | 0.29 |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 0.22 |

| Akron, OH | 0.19 |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | 0.19 |

| Boise City, ID | 0.18 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | 0.18 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | 0.16 |

| Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY | 0.15 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 0.14 |

source: “The Case for Growth Centers,” ITIF and Brookings, December 2019

You call for banning incentives for Chinese FDI in the United States. Legitimate Chinese companies meanwhile continue to invest in major job-creating facilities worldwide. Would you welcome un-incentivized Chinese FDI?

Rob Atkinson: Yes, I would — as long as it doesn’t involve the acquisition of an American company. If a Chinese firm wants to build a factory in the U.S., for example, in most cases that kind of greenfield investment would be acceptable. What I strongly object to is state governments subsidizing those investments with public funds. There is no compelling reason for U.S. taxpayers to underwrite Chinese state-affiliated enterprises when those resources could be better used to bolster domestic industry.

More broadly, the federal government’s top priority should be protecting and revitalizing the United States’ advanced industry capabilities. China is not simply participating in a level global playing field — it is actively pursuing a mercantilist, state-directed strategy to dominate key sectors and gain global market share at the expense of foreign competitors. On a case-by-case basis, some Chinese FDI may provide economic benefits to the U.S., such as jobs or localized growth. But it’s important to recognize that a significant share of Chinese investment is guided or supported by Beijing as part of an “‘indigenous innovation” strategy that targets strategic sectors vital to U.S. national security and technological leadership. That reality must shape how we evaluate and regulate these investments.

Your graph of states’ global LQs shows how they compare to China’s LQ but doesn’t include any other nations’ LQs. Give me a sense of how other nations known for their advanced industries measure up in such a graph.

Rob Atkinson: While not the same comparison, the 2023 Hamilton Index offers broader international context by comparing 40 countries based on their location quotients (LQs) across 10 strategically important advanced industries. Some topline findings from that analysis include:

“Fourteen countries have LQs above average for the composite output of the 10 industries, with Taiwan ranking first at 2.1 (with almost all of that driven by its computer and semiconductor output). Three other East Asian nations — Korea, Singapore, China, and Japan ranked second, third, fifth and seventh, respectively. This in large part reflects the focused and dedicated advanced industry policies these nations have had in place for the last several decades.”

The engineering- and chemical industry-intensive nations of Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, and Austria ranked fourth, sixth, ninth, and eleventh, respectively. The United States’ LQ was 0.87, meaning that as a share of U.S. GDP, these industries collectively are smaller than the global average. For the U.S. LQ to be 1.0, advanced industry output would need to expand by $328 billion, or 15%. This would be equivalent to doubling America’s computer, electronics and optical products industry output.”

While your recommendations focus on federal economic development policy, there is a growing movement for regions to pursue sub-national diplomacy, commerce and trade initiatives with foreign regions around the world. How do you view this trend in terms of advancing advanced industries partnerships and collaboration, whether because of or in spite of federal policy?

Rob Atkinson: Sub-national engagement can play a valuable role, especially among large metro areas and states with robust industry and research sectors. But it’s critical that these efforts align with national policy goals. That said, some regional initiatives can undermine national interests. For instance, certain sister city partnerships with China may be inappropriate. We’ve seen governors pursue economic deals with China that don’t necessarily align with U.S. strategic priorities. So, while regional diplomacy has potential, federal alignment is non-negotiable.