Whether you like what nuclear weapons have accomplished or not, there’s no debating the fact that they still exist. That means a continuing program of high-tech manufacturing and maintenance services that would not shy away from being called a military-industrial complex.

The footprint of that complex is about to simplify in one place at least, and save the federal government $100 million a year in the process.

In June the General Services Administration signed a lease with CenterPoint Zimmer — an affiliate of CenterPoint Properties Trust — for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) National Security Campus in South Kansas City. The project will bring approximately 1,500 new construction jobs to the region, and preserve more than 2,500 jobs at the campus. The total cost of the new complex, including design, construction, equipment, and payments on the 20-year credit-tenant lease, is estimated at several billion dollars.

“This milestone is a significant step in transforming an outdated, Cold War-era nuclear weapons complex into a 21st Century Nuclear Security Enterprise that is positioned to achieve the vision articulated in the recently released Nuclear Posture Review,” said Tom D’Agostino, NNSA administrator.

Operated by Honeywell Federal Manufacturing & Technologies, the plant produces and assembles non-nuclear components for the nation’s nuclear weapons. Among other things, the transformation will reduce the cost of the facility’s operations by 25 percent (that $100 million) and reduces the size and capacity of that mission by two-thirds, or some 2 million sq. ft. (185,800 sq. m.). Private financing and a 20-year GSA leaseback arrangement with CenterPoint Zimmer, LLC, allow for what the GSA calls “dynamic business model changes.” And energy-efficiency plans will reduce energy consumption by more than 50 percent, as the facility aims to be one of the first LEED-Gold manufacturing campuses in the nation.

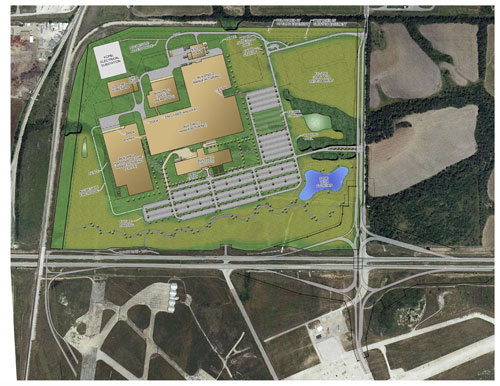

The campus will be located on 177 acres (72 hectares) that until now was a farm field at the northeast corner of Missouri Highway 150 and Botts Road, eight miles (13 km.) south of the NNSA’s current location, still known to native Kansas Citians of a certain age as “the Bendix plant.” The parcel is not far from another property that recently was being considered by K.C.-based Cerner Corp. for an expansion project. The new complex will be owned by the Planned Industrial Expansion Authority of Kansas City (PIEA), a state-chartered development agency. Ground was scheduled to be broken this month. A phased move is scheduled to begin in late 2012, with full occupancy by 2014.

Established in 1949, the Kansas City Plant operated today by Honeywell comprises the largest portion of the 5.2-million-sq.-ft. (483,080-sq.-m.) Bannister Federal Complex, built in 1942 by the Navy during World War II to assemble engines for Navy fighter planes. The complex was operated by Pratt-Whitney from early 1943 until Sept. 2, 1945, and produced the famous “Double Wasp” engines for the Navy. In February of 1949 the Atomic Energy Commission asked the Bendix Corp. to manage the facility and build non-nuclear components for nuclear weapons.

Today the facility employs 2,462 people. The entity known as “the Kansas City Plant” also includes 266 employees working out of locations in New Mexico, Arkansas and other locations, and reported a fiscal year 2009 overall payroll of $341 million. The average salary figure in K.C. alone hovers around $95,000. The facility paid $1.7 million in Kansas City earnings tax in FY 2009 and spent $15.7 million on small business procurement contracts in Missouri and Kansas.

The new campus will include 1,509,950 rentable sq. ft. (140,275 sq. m.) of space, comprising manufacturing, warehouse, office and R&D activities. The lease includes an annual rent of $61,558,772.00. Total contract value over the 20-year term is more than $1.2 billion. Zimmer Real Estate Services of Kansas City, Mo., will be the property manager for the new campus and a development consultant to CenterPoint Zimmer LLC during construction. Other contractors include HNTB Architects of Kansas City, Mo.; SSOE, Inc. of Toledo, Ohio; Pro2Serve of Oak Ridge, Tenn.; Johnson Controls of Lenexa, Kan.; and JE Dunn Construction of Kansas City, Mo.

“It was a tough road getting to this day, but teamwork prevailed in the end,” said Jason Klumb, GSA regional Administrator. “All of our partners with the city, the development teams, NNSA and contractors deserve credit for this success.”

Can We Have a Do-Over?

Timing is everything. When it’s off, the second time can be a charm.

GSA partnered with the National Nuclear Security Administration in 2006 to assist with the real estate needs associated with the transformation of the Kansas City Plant. As its own history of the project explains, “GSA’s first solicitation for a developer was announced in October 2007. However, the unforeseen economic turmoil of 2008 prevented bidders from meeting the solicitation’s original requirements.

“After about eight months of going through the procurement process, we had a bid bust,” explains Charlie Cook, regional public affairs officer for the GSA. “All the developers in the game came to us and said ‘We are having trouble finding funding sources.’ So we cancelled the solicitation. At that point GSA got together with NNSA, and they still wanted to pursue the plan.”

Kyle Gore, managing director of CGA Capital Corp., says the bid bust was caused by “an inability to match available funding to the capital cost implied by the specifications proposed at that time.” Baltimore-based CGA and its affiliates closed the financing deal, worth some $687 million, in July. CGA served as exclusive financial adviser and structuring agent for the public-private venture, and was the sole arranger of the private placement of bonds through a venture with a privately held securities firm, Bostonia.

Based in part on specific cost-cutting advice from CenterPoint, the solicitation was restructured. The GSA also went to the city of Kansas City, which brought to the table the idea of doing the project through the PIEA. Among the benefits conferred by such an approach: deferral of up to 100 percent of property taxes, and some sales tax reductions. And going from a federally owned facility to a new private lease generates income for the city, around $5.3 million a year in new taxes. Cook says GSA agreed to about half of that, which still ends up paying $2.25 million more into city coffers than before. A bond package worth $815 million was approved by the authority in May.

“Ultimately the structure changed a bit,” says Cook. “The city did their own bid process, and GSA reissued a solicitation, requiring that if you want to win the project you have to win both of the solicitations.”

“At the time it was very frustrating,” says Gore. “It was all on goodwill. It wasn’t for fees or ongoing compensation. A lot of people with significant resources and experience — and significant other opportunities — made a decision to step up and not only do it the first time, but then to continue. Everyone had a decision at that point, and doubled down and said ‘Let’s do it again.’ CenterPoint spent untold thousands of man hours and millions of pre-development dollars for the privilege of holding a couple of die in their hands and hoping they would come up sevens.”

The second solicitation went out in July 2008. CenterPoint Zimmer was selected as the developer in April 2009. Then environmental litigation raised its head, as plaintiffs cited continuing issues at the current plant site, and that environmental considerations had been inadequately addressed at the new site.

“Among the relief that was requested was an injunction against them [GSA] entering into a new lease at this new facility,” explains Fred Wolf II, a partner in the real estate department at Ballard Spahr, which worked with CGA in overseeing the creation and negotiation of all loan documentation and had a major role in completing all lease and construction documents associated with the project. “Until that litigation was resolved, it was a considerable impediment to proceeding forward.”

In the meantime, CenterPoint was working with its partners on hundreds of pages of detailed design specs. Then, in January, the litigation was dropped, a few months after a federal judge had sided with the government.

“Was it about the environment, or people who didn’t want to see nuclear weapons plants?” asks Gore. “You have to have this kind of facility, and you should be thankful we do. There are already nuclear weapons, and they must be maintained, even if only to prevent bad things from happening.”

“To Gore’s admittedly layman’s eye, the time for an update was well past due at the gargantuan, legacy complex. And the simple scale of the space no longer seemed appropriate. “It’s incredibly inefficient, when you think about heating and cooling this a monster facility. The structure was built in an era when you needed a room to house a computer with the same power as your Blackberry. “

The Way Forward

“NNSA literally owns and operates 3.2 million square feet [297,280 sq. m.] of the total building, and the remainder is owned and operated by the GSA,” says the GSA’s Charlie Cook. “They are two properties, on each agency’s books, and firewalls divide the property line. There is no way for people to walk back and forth. That’s the situation we exist in today.”

And it’s been the situation for some time. So in the early 2000s, NNSA developed the Kansas City Responsive Infrastructure Manufacturing and Sourcing plan, designed to streamline manufacturing and increase sourcing. (Got some time? Check out the full 233-pp. document here.)

“NNSA, being a landholding agency, didn’t really need GSA’s input,” says Cook. “They can get their own land, go to Congress and ask for money. This is the first deal we’ve done like this. They came next door to give us a heads up, saying, ‘We’re going to move,’ and find a facility here or somewhere else in the country. After NNSA approached GSA, we said we would support whatever decision they made as long as they could provide they needed to relocate from the current complex. We explored several different options, including remodeling the current building, tearing down the current facility and rebuilding on the site, or pursuing a build-to-suit lease. After reviewing the different options, GSA and NNSA settled on the build-to-suit lease — which is an authority GSA has that NNSA does not.”

While several options were examined, the choice of the new campus site came after studying the commuting scattergram of current employees and evaluating whether to demolish and rebuild on the same site or not. Utlimately the greenfield site won the day, and so did the new real estate plan, arranged like so many nesting dolls.

“At the end of the day, after all these years of planning, you have a situation where the city, through the Planned Industrial Expansion Authority, will own the property, lease it to CenterPoint, who will then lease it to GSA, which is essentially the broker for the federal government,” explains Cook. “We then have an occupancy agreement wit the NNSA, and they have a contract with Honeywell. So it’s quite the complex project. I’ve never seen nor heard of anything like this before. There were times we weren’t exactly confident it would work, but no one was ready to give up on it. I think it was our combined determination that kept the project alive through the economic downturn.”

Wolf says what made the deal especially complex were legal constraints within which authorities such as PIEA and GSA must operate. “The key was to figure out a way to structure the financing so they would be authorized to do what they had to do.” Examples include language pertaining to adequate remedy should default occur during construction, and GSA’s commitment to make rent and payment-in-lieu-of-taxes payments.

Gore notes that the 2008 financial crisis only further supported the decision made in 2007 to focus on leaseback bond financing. He also mentions particular aspects of the deal structure.

“The structure includes monetizing not just the GSA lease, but also a portion of those PILOT payments,” he says. Infrastructure support aspects of the projects such as a new highway overpass and sewer lines were originally to be financed by the PIEA using the PILOT payments. Now it is CenterPoint-related entities making those payments.

Just the Beginning

Gore says CenterPoint really led the charge in all respects. The Illinois-based developer knows the area well, as it owns land literally across the street from the newly chosen campus site, where it’s redeveloping part of the former Richards Gebaur Air Force Base into an intermodal facility.

“As CenterPoint notes, at the end of the day it’s a suburban office building stapled to a warehouse/manufacturing space on steroids,” he says. Equally important is a cast of contractors that includes firms such as JE Dunn, which recently completed the new IRS service center in Kansas City, “which ironically also relocated people from the Bannister complex,” says Gore. The other contractors possess unique experience in integrating all the mechanical and engineering details associated with national security-linked facilities. Gore’s team came into the picture when it was still part of RBS Greenwich Capital, from which CGA spun off. The team had worked with CenterPoint before on one of its intermodal properties.

Asked about the opportunity for more such lease-backs that could save the government money, Gore says, “There is not a month or week that goes by that we don’t hear about some other effort to replace an older, aging government facility, though it may be months or years away.” Examples are in the news, such as a plan to replace aging buildings at Fort Meade in Maryland.

In fact, one such effort may be the rest of the Bannister Federal Complex. The process has been set in motion to petition Congress for a new facility in Kansas City, moving the complex’s remaining tenants so that 100-percent vacancy was achieved and the government’s public disposal process could be pursued.

“You could weave an argument about the need to upgrade our crumbling infrastructure,” says Gore. “Is the government better served by doing these kinds of projects with government funding or with a public-private effort like this? The private sector is better equipped to build things like this, manage them, and make sure they’re on time and on budget.

“In a way there are huge swaths of government real estate that need to be upgraded,” Gore says. “We think the opportunity is ripe for engaging in this kind of transaction activity on other government facilities.”