A prerequisite for a high-quality workforce is people. To upskill employees, attract remote workers, or fill a skill gap through a community college program, you first need people. That may be rather obvious, but talent attraction and retention efforts have been built on the assumption that when it comes to people, the harvest will always be plentiful. But what happens if the supply of people to attract to, or retain in, a community isn’t increasing? Or what if it’s decreasing?

In The Demographic Drought, Emsi Burning Glass raised the alarm bells about the pending sansdemic (sans-without, demic-people). Due to an increase in baby boomers retiring, a continual decline in prime-age male labor force participation, and decades of low birth rates, in the coming years the U.S. (and much of the world) simply won’t have enough people for all the work that needs to be done.

This shortage will affect quality of life, result in higher prices for consumers, and diminish the speed and quality of services. In many ways, the labor shortage and supply chain issues we are experiencing now are a foretaste of what’s to come. Gone will be the days of businesses trying to find the best talent pools for their expansion or relocation. Just finding people to fill openings will be the goal.

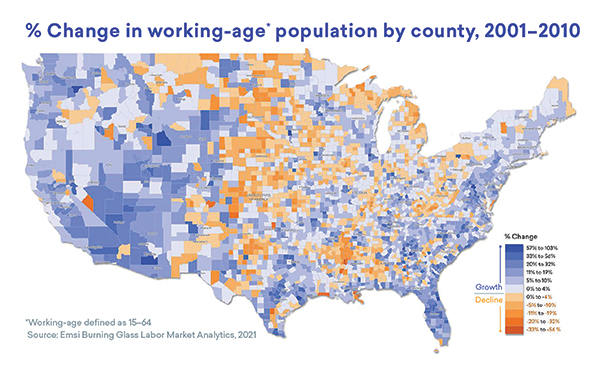

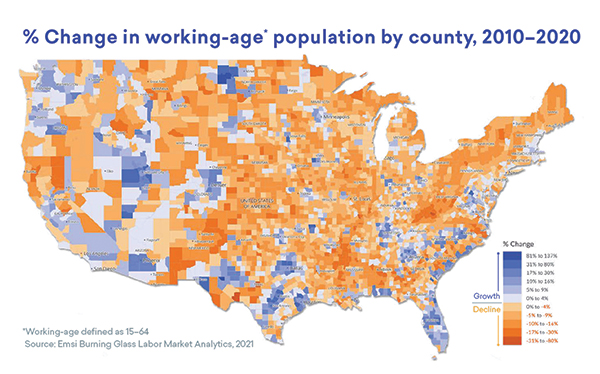

For communities cultivating talent (both attracting and retaining), those with growth rates in their under-15 population and working-age population (age 15-64) will have a distinct advantage in the sansdemic, as they will have the pipeline needed to support employers. Communities that play the best defense — develop mitigation tactics — will be the runners-up in this new world of not just competing for talent but competing for a diminishing supply of talent.

Scorecard Takeaways

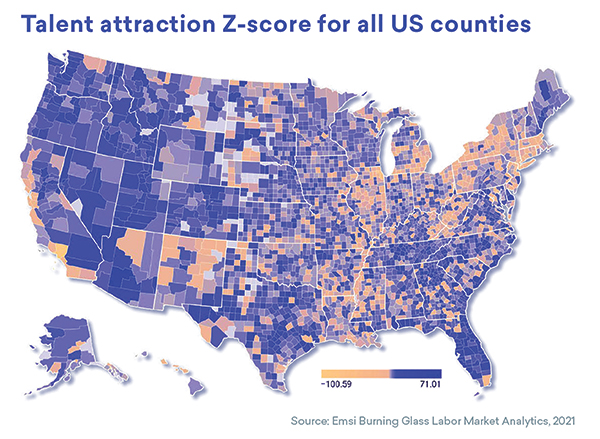

We’re already beginning to see this advantage play out. In our sixth annual Talent Attraction Scorecard, counties with the largest growth in working-age population all rank in the top 50 of large counties. Meanwhile, those with the biggest reductions in working-age population dominate the bottom of the rankings.

In the Scorecard, which creates an index based on migration, growth of overall and skilled jobs, regional competitiveness, job openings per capita, and education attainment, two other themes emerged. First, suburbs and exurbs continue to be an attractive option for movers. Census data over the last decade reinforces a theme in the Scorecard rankings:

Counties surrounding major metros, often the suburbs and exurbs of those metros, are growing. Professional migration data reveals a continuation of this trend in 2020. When people leave the largest U.S. metro counties, the most common destination is an adjacent county. Of movers out of the five most populated cities, the vast majority went to surrounding counties. The exception was Phoenix residents, who opted for southern California counties.

Second, some regional stratification is occurring. Texas and Florida placed 23 counties in the top 40 of the Scorecard’s large county category, continuing to separate themselves from the pack. Regionally, the Northwest, Mountain West, and Southeast had high marks, with the Northeast struggling. To what degree politics affects these shifts is unclear, but our large county rankings generally tend to align with the anecdotal narrative over the last few years of migration from blue to red states.

This year’s Scorecard demonstrates that talent development strategies are first and foremost people strategies. Much of the strategizing around talent development will require a mind shift: less about buying (communities attracting talent with amenities or businesses upping salaries to steal away talent) and more about building: valuing people more and investing in them every step of the way.

Drew Repp is a marketing manager at Emsi Burning Glass, Moscow, Idaho. Contact him at drew.repp@emsibg.com.