In a pandemic-driven season that saw a surge of e-commerce, our Top Metros feature a strong presence of logistics hubs like Chicago, the Midwest megaregion that returns to its spot at the top of our Tier 1 rankings.

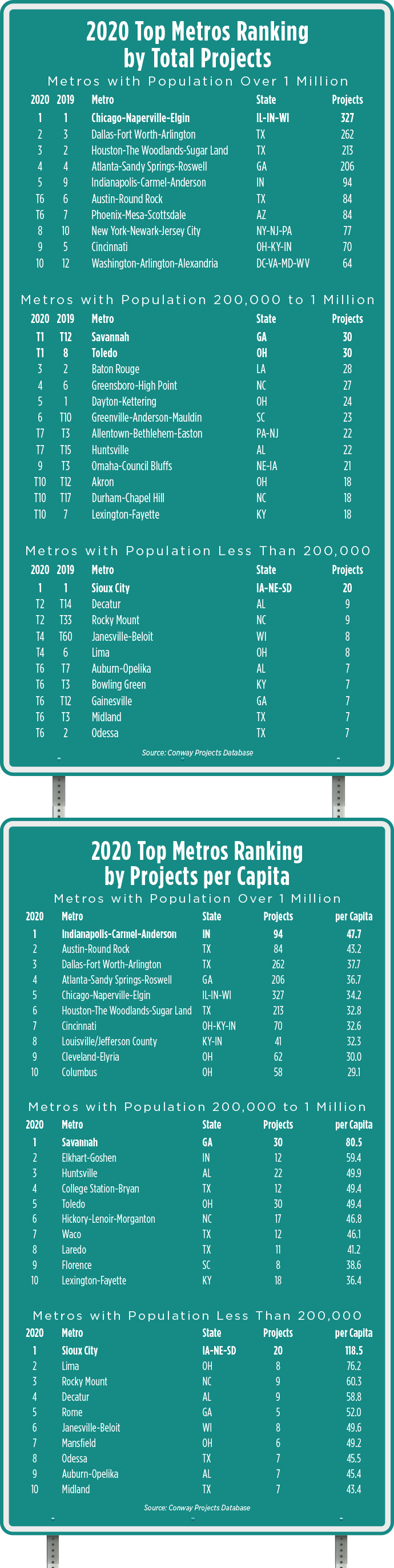

Indeed, the Midwest makes a resounding statement with not just Chicago, but Toledo, Ohio, and Sioux City, Iowa, emerging from the nationwide pack as Tier 2 and Tier 3 winners, Toledo sharing its first-place finish with fellow first-timer Savannah, Georgia.

You’re likely to see new names being saluted in the ranking charts that follow, regions such as Elkhart-Goshen, Indiana, home to more than 80% of global RV production, and thus “the RV Capital of the World.” Our newly introduced Top Metros Per Capita rankings unearthed hidden gems such as Elkhart-Goshen, Hickory-Lenoir-Morganton, North Carolina; Laredo, Texas; Decatur, Alabama; and Janesville-Beloit, Wisconsin.

Notably, as well, Indianapolis edged past Chicago into the top spot per capita among Tier 1 metros. The Indy region also climbed to No.5 in our cumulative ranking (project tally only), having never placed higher than No. 9 in the past five years. Reflecting the unique circumstances of 2020, the Indianapolis metro’s biggest investment came from one of the world’s leading producers of wet wipes, highly sought for anti-viral protection. Arkansas-based Nice-Pak announced plans in December for a $165 million manufacturing and distribution center with 150 jobs.

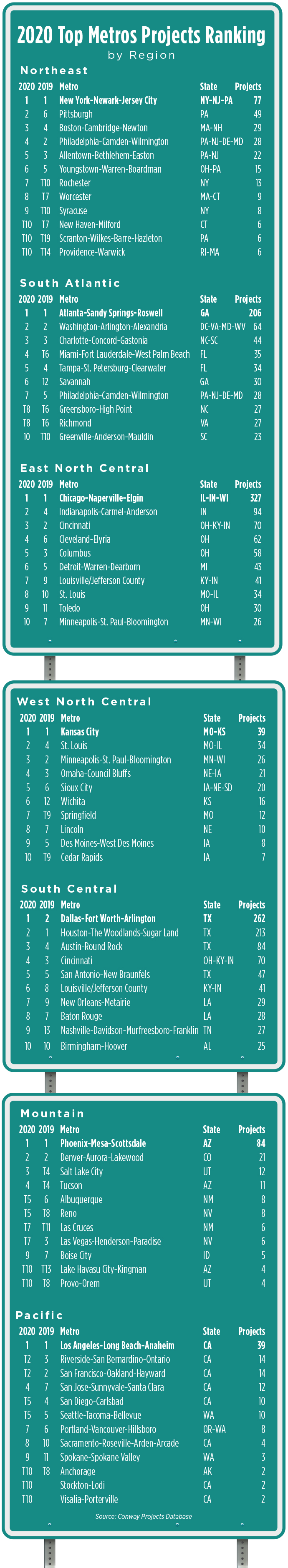

Site Selection’s Top Metros rankings are based on accumulations of major capital investments in corporate end user facilities within a given core-based statistical area (CBSA) or metropolitan statistical area (MSA), as defined by the Census Bureau. Such areas can bleed across multiple jurisdictions, even states. Qualifying projects are tracked by Site Selection’s proprietary Conway Data Projects Database, which qualifies investments that meet at least one of three criteria: a minimum $1 million capex; 20 or more jobs created; or 20,000 sq. ft. or more of new space.

We divide metros into three tiers, according to population. It is our own calibration, but one you might see emulated elsewhere. Tier 1 metros are those with more than a million residents. Tier 2 populations range from 200,000 to 1 million, and Tier 3 metros have populations of less than 200,000. We address “Top Micropolitans” in a separate report found on p. 109 of this issue.

New Trends, and Chicago Still Wins

Ask around about the industrial real estate market in Chicago and you’ll hear words like “insane,” “staggering” and “wild.” In its year-end report, Colliers International characterized 2020 as a record year for Chicago, with 48.6 million sq. ft. (4,515,090 sq. m.) of new industrial leases signed, a 28% increase from 2019. That, in a pandemic year.

It’s indicative of a nationwide trend. As CBRE wrote in a year-end report:

“The U.S. industrial market cemented itself as the most in-demand commercial property sector in 2020, fueled by a large increase in e-commerce sales due to COVID-19 restrictions. Demand for industrial buildings of all sizes surpassed 2019 totals but [was] strongest in mega-distribution facilities of 1 million sq. ft. or more. The top 100 transactions last year totaled 103.8 million sq. ft., 17% above 2019’s total.”

“The institutional developers really started catching on about 24 months ago.”

Of the Chicago metro’s top-ranking 327 qualifying projects, a hefty 203 have a connection to warehousing and distribution, as e-commerce rocked the market. Another relevant piece of data: A total of 23 qualifying projects in Chicago can be attributed to just one investor: Amazon. Amazon’s investments in Chicago, totaling in the hundreds of millions of dollars, prompted Crain’s Chicago Business to declare in August that, “the Seattle-based e-commerce giant has emerged as the Chicago economy’s biggest growth engine.”

In addition to facilitating pandemic-driven demand for home delivery, Amazon’s spree is partly a matter of making up for lost time in Chicago, according to Scott Gibbel, vice president-Chicago for national developer IDI Logistics.

“Amazon was slow to establish their footprint in the Chicago market, initially servicing the area out of southeast Wisconsin and the far west suburbs,” Gibbel tells Site Selection. “Then, at the start of 2020 they really ramped up their local network, absorbing over 15 million sq. ft. [1,393,00 sq. m.] in the Chicago market. Why? Because there are over 9 million people in the Chicagoland area that are buying online and they didn’t have the infrastructure in place to support that.”

While notably prolific, Amazon is far from the only retailer beefing up its distribution capabilities in Chicagoland, a market within 750 miles (1,207 km.) of 42% of the nation’s population. Qualifying investments in warehousing and distribution came from Target (991,000 sq. ft./92,065 sq. m.); Walmart (192,000 sq. ft./17,840 sq. m.); Ace Hardware (180,000 sq. ft./16,720 sq. m.); Home Depot (120,000 sq. ft./11,150 sq. m.) and Lowe’s (115,000 sq. ft./10,689 sq. m.).

The pandemic, market analysts say, has accelerated momentum toward “just-in-case” inventory management, which means keeping extra product on hand for on-demand delivery, thus mandating expanded storage space.

“Remember,” says Gibbel, “we couldn’t buy paper towels and toilet paper. How is that possible? Retailers learned quickly how costly stockouts are, and they are strategically expanding their warehousing requirements to accommodate additional safety stock.”

That same fear of missing a sale, says Gibbel, prompted retailers to bite the bullet in 2020 and pay a premium for air shipments from overseas to avoid ocean shipping bottlenecks. Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport thus handled $200 billion worth of freight in 2020, tops in the U.S.

“We can’t build warehousing quickly enough around O’Hare Airport,” says Patrick Turner, senior vice president, Colliers Chicago. “As quickly as these new facilities are being constructed, they’re being leased. If you have a good site close to the airport, you’re going to have a dozen interested parties fighting it out to see who can get control of it. The competition is that fierce.”

Third party logistics providers (3PLs) are “blowing it up” in Chicago, says Gibbel. The 3PL investments in the Chicago market totaled in the tens of millions of square feet, with SRC Logistics of Springfield, Illinois, leading the way with a 1-million-sq.-ft. (92,900-sq.-m.) warehouse in the Joliet submarket. Other such investments include those by: Geodis (400,000 sq. ft./3,160 sq. m.); Quality Custom Distribution (356,000 sq. ft./33,075 sq. m.); Champion Packaging and Distribution (283,000 sq. Ft./26,290 sq. m.) and Lineage Logistics (241,000 sq. ft./22,390 sq. m.).

IDI, says Gibbel, expects to break ground over the next 12 months on at least three speculative warehousing projects, a sign of the developer’s confidence in the continuing verve of the Chicago market, pandemic or no.

“The growth and adoption of e-commerce was already happening,” says Gibbel. “This pandemic just acted as an accelerant, and developers are adapting with users on supply chain solutions. This trend will help contribute to what many believe will be a record year for new leasing activity.”

Savannah: How Do You Like Me Now?

Savannah, Georgia, vaults all the way into Site Selection’s top spot for Tier 2 Metros (tied with Toledo, Ohio) after finishing No. 12 in last year’s rankings. Further cementing its accomplishment, the port city on the Atlantic claimed the top spot for Tier 2s in our new Per Capita rankings. It’s a rare set of circumstances. What happened?

With 30 qualifying investments, Savannah, like Chicago, has been the beneficiary of the e-commerce explosion. The Port of Savannah, which boasts the largest single container terminal in the Western Hemisphere and dominates the regional economy, registered some of its biggest months ever as the pandemic year of 2020 came to a close.

Savannah’s upward trend began in earnest with the 2016 expansion of the Panama Canal, says Griff Lynch, executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority, which owns the Port of Savannah. The canal’s accommodation of larger container ships has allowed the East Coast to steadily siphon traffic from Asia that traditionally docked at the ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Francisco and Seattle.

“In this industry, things don’t happen overnight,” says Lynch. “That line of demarcation between what’s the best service for East Coast versus West Coast has changed over time. The West Coast just doesn’t have the capability to absorb the type of growth that’s coming to our country right now.”

When the business came, Savannah was ready. As an operator-owned facility, the port makes improvements and upgrades to the tune of $100 million a year, and more. Late this year or early next, a six-year, five-foot deepening of 39 miles (63 km.) of the channel connecting the Savannah port to the Atlantic Ocean is expected to come to fruition.

“For every foot of depth,” says Lynch, “a large vessel can take another 200 containers onboard. That’s an interesting stat,” he says, “because it means ships could do 1,000 more moves here if they needed to.”

An essential enabler of the port’s steady growth has been the rapid expansion of distribution space within the Savannah market. Trip Tollison, president and CEO of the Savannah Economic Development Authority (SEDA), says the region’s warehousing footprint has grown from some 15 million sq. ft. (1.4 million sq. m.) in 2005 to 77.5 million sq. ft. (7.2 million sq. m.) at the end of 2020, with 10% of that having come online during the COVID year.

“The institutional developers really started catching on about 24 months ago, and it’s been crazy, like the Wild West,” says Tollison. “They come in and they make things happen fast. We have to make sure we have the product there when they come calling.”

Backed by Stravinsky Capital Management of Massachusetts, Savannah’s Port City Logistics is developing a 1.1-million sq.-ft. (102,000-sq.-m.) headquarters and distribution facility at Port Wentworth, a few hundred yards from the Port of Savannah’s Garden City Terminal. As the region’s biggest current industrial-related development, the project is expected to create some 200 jobs through an investment of $80 million.

Of Savannah’s 30 investments that merited inclusion in our Conway Projects Database, fully 26 are related to warehousing and distribution. As regional economies seek diversity, is that too many eggs in one basket?

“We’re concerned about that,” Tollison concedes.

To bolster the Savannah region’s manufacturing sector, whose crown jewel is Gulfstream Aerospace, SEDA is nearing completion of the 800-acre (325-hectare), $38 million Savannah Manufacturing Center, funded in large part by sales tax proceeds. Phase One includes just over 2.5 million sq. ft. (232,000 sq. m.) of industrial building space with parcels from eight acres (3.2 hectares) to 88 acres (36 hectares).

Savannah’s evolving tourism industry, which earned a record $3 billion in 2019, looks to rebound in 2021 from its COVID slump, as does a nascent film production space. SCAD, the internationally known Savannah College of Art and Design, is an emerging beacon of culture that consistently ranks as one of the top film schools in the country.

“It’s incumbent upon us as a development authority to really honor, cultivate and maintain what we have,” says Tollison. “But shame on us if we’re not doing all we can to further diversify our economy. We’re spending a lot of time doing that.”

Toledo’s Triumph

It’s been a long time coming for Toledo, Ohio. A consistent Top 10 finisher among Tier 2 metros, the port city on the western end of Lake Erie took a path fundamentally different from Savannah’s on its way to a share of the winner’s circle.

Toledo attracted 20 manufacturing investments among its haul of 30 qualifying projects. The Toledo metro’s accomplishment further serves as validation of a region that’s true to its industrial roots as it envisions a dramatically different future.

“If someone wants to call us ‘Rust Belt,’ fine,” declares Wade Kapszukiewicz, Toledo’s young, high-energy mayor, now completing his first term. “I like to think of us as the Fresh Water Belt. At a time when the country and the world are getting more and more desperate for fresh water, we here in the Great Lakes region are sitting on 20% of the uncapped fresh water on planet Earth. And that will be a tremendous strategic advantage to us if we can just figure out how to harness it.”

“If someone wants to call us ‘Rust Belt,’ fine. I like to think of us as the Fresh Water Belt.”

Those are not empty words. In 2019, Kapszukiewicz (pronounced: KAP-soo-KAA-vich), helped to forge a regional water agreement that “had eluded northwest Ohio for 50 years,” he says. The pact ended what was a byzantine, regional competition by establishing a uniform contract for water supply among Toledo and its suburbs. Kapszukiewicz cites it as among his top accomplishments. He also has shored up Toledo’s budget, resulting in a record Rainy Day fund of $70 million. He sees taxpayers’ approval of two infrastructure bonds last November as one of many signs of creeping optimism.

“The mere fact that those measures passed during the middle of this pandemic shows that the citizens of Toledo are optimistic, that they believe in their future. Why on Earth,” he asks, “would you reach in your pocket like that if you didn’t think there are better days ahead?”

Prakash “P.K.” Karamchandani is one of those optimists. A University of Toledo graduate, Karamchandani and fellow alum HoChan Jang opened Balance Grille and Balance Farms in 2018 at the Tower on the Maumee, a formerly vacant 30-story skyscraper newly restored with high-end apartments, office space and retail. Balance Farms is an 8,600-sq.-ft. (800-sq.-m.) aquaponics farm that supplies the vegetarian-leaning menu of the adjacent Balance Grille (now with five locations in northern Ohio) and other Toledo restaurants.

“As I look to the next 20 years as my daughter comes of age, Toledo, like a lot of places in the Midwest, has all the classic infrastructure,” Karamchandani tells Site Selection. “Innovation moved from here to the coasts, but now the coasts are so expensive. What COVID has shown us is that technology is going to facilitate the ability for people to innovate in places, like Toledo, that have a lower cost of living and a better quality of life.”

Similarly, Kapszukiewicz is among those who sees expanding possibilities, post-COVID, for Tier 2 metros like Toledo.

“We are excited and we are well positioned to continue to build on our momentum,” he says. “We’re not New York City. We don’t want to be New York City. We’re proud of who we are, where we’ve come from and where we’re going.”

The Staying Power of Sioux City

Mike Wells, CEO of Wells Enterprises, tells a poignant story about the founding of his family’s ice cream business just northeast of Sioux City, Iowa. In 1913, his great uncle, Fred Wells, was heading home to Chicago after an ill-fated attempt at homesteading in South Dakota.

“He got as far as Le Mars and he literally ran out of money,” Mike Wells says. Fred Wells managed to procure a horse and wagon and began delivering milk, soon to try his hand at making and selling ice cream. Today, the company he so modestly founded ranks second in size among America’s ice cream makers, and Le Mars thus calls itself “the Ice Cream Capital of the World.”

“We haven’t looked back,” Wells says.

The cream rises to the top again, as the Sioux City metro (officially Sioux City, Iowa-Nebraska-South Dakota) returns as Site Selection’s top Tier 3 metro. The region has accumulated a resounding record of success, having claimed the top spot nine times since 2007 and having otherwise ranked second or third.

Wells, board chair of the Siouxland Chamber of Commerce and the Siouxland Initiative, is well positioned to explain the region’s success. He’s been in business there for 44 years.

“We’ve learned the formula on how to market ourselves, but we also have the distinct advantage of having what people want. We’ve got access to plentiful water. We’ve got multiple suppliers of gas and electric and water. We’ve got infrastructure and access to the shipping lanes on the Missouri River.”

Those are standard selling points, but Wells believes there’s something bigger at work, something consistent with being a modestly sized community in the Midwest.

“We not only see the benefit of attracting new folks to our community, we welcome them in. When we bring prospects to our community and we have them rub elbows with other businesspeople and just people in general, they get a sense that this is a community of people that care.”

With companies like Wells leading the way, food and nutrition are central to the Siouxland economy. Major meat processors include Tyson Foods and Seaboard Triumph. CF Industries, in 2020, invested another $5.5 million in its fertilizer operation, and Empirical Foods expanded a beef plant. Royal Canin Pet Foods did a major expansion the year before. An Interbake Foods cookie bakery employs more than 500 people.

Siouxland does manufacturing, too, as illustrated by the diversity of its 20 qualifying projects for 2020, 11 of which have a manufacturing connection. Sabre Industries, one of the country’s largest suppliers of steel poles for utilities and telecommunications, is expanding again to meet a healthy demand sparked by wind energy farms and their electric transmission lines. Sabre’s $25 million capital investment is to create 76 new jobs at its facility in Sioux City’s Southbridge Business Park. Other 2020 manufacturing investments include those by Fimco, which calls itself the country’s largest maker of lawn and garden sprayers, and NextBeam, a company that sterilizes animal cages.

To refer to the region as Siouxland is to mitigate potential confusion that might arise from an area anchored by three Sioux Cities, include South Sioux City, Nebraska, and North Sioux City, South Dakota. All are within five minutes’ drive of each other. For Chris McGowan, president of the Siouxland Chamber of Commerce, this tri-state arrangement on steroids offers a distinct advantage in business recruitment.

“When our organization is pursuing economic development prospects, we typically will have three unique geographical locations with diverse economic development incentive offerings depending on the community in the state. There’s no doubt in my mind,” says McGowan, “that that has helped us be successful because, depending on the nature of the company we are pursuing, there may be state legislation that is particularly favorable to that industry, or to a company within that industry.”

Beyond that, he says, it makes for an interesting way of life.

“You might have a day that begins with playing golf in South Dakota, leading to a nice dinner in Nebraska and then a Broadway show in Iowa. That,” he says, “is a good day.”