As the Atlanta Falcons have battled their way to this week’s Super Bowl, the chorus of fans joining in the team’s gospel-choir “Rise Up” anthem has only grown more fervent. But the momentum of the news cycle also has stoked the fire in this metro area of 6 million.

The 5th Congressional District comprising most of Atlanta is in the spotlight because of U.S. Congressman John Lewis’s questioning of President Donald Trump’s legitimacy and policies, which prompted the president to call Lewis’s district “in horrible shape,” “falling apart” and “crime-infested.”

Atlanta, of course, has a long history of fighting back. It was a bulwark of the Confederacy in one century, and a civil rights hot spot in the next. There was no reason to think it would fall back silent in this instance. The defense of the city’s economic vibrancy, diversity and cultural dynamism from all quarters has been fast and furious, highlighting assets ranging from the federal Centers for Disease Control to new corporate headquarters to the area’s multiple high-ranked universities.

Two projects among many underway today point to a city where resistance may still smolder, but resilience fuels the flame. Rather than wait around and talk about it, the city’s already rising to challenges with loud-speaking actions.

A New Neighborhood in the Old

When Lewis introduced a resolution in September recognizing the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in the nation’s capital, he was indirectly also recognizing the work of a national construction leader based in his own backyard: H.J. Russell & Company, which partnered with Clark Construction and Smoot Construction to build the unique structure.

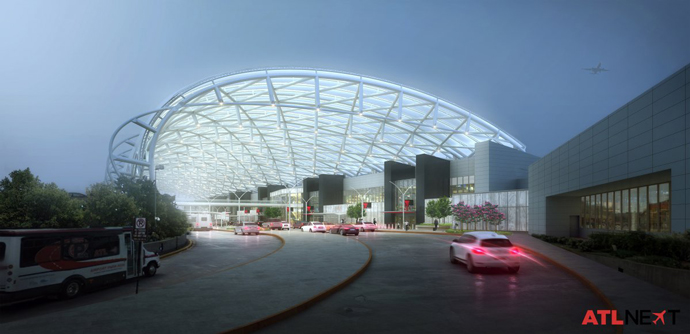

Founded in 1953 in Atlanta, H.J. Russell & Co. helped build much of the Atlanta we know today. It is the largest minority-owned real estate and construction company in the U.S., and has been involved in such projects as the DFW terminal renovation and Parkland Hospital and Skybridges projects in Dallas and ongoing redevelopment projects at Philips Arena and Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The Russell family also owns Concessions International, the largest African American-owned airport concessions company in the country.

The company’s late founder Herman Russell and generations to follow have demonstrated a commitment to urban renewal, community building and civil rights. Russell’s home in the historic Colliers Heights neighborhood was a gathering place in the 1960s for influential civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis, Andrew Young and former Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson. Cause and commerce sometimes align too: The firm was involved in the construction of the city’s striking new Center for Civil and Human Rights.

The company last year relocated its headquarters from the near-West Side Castleberry Hill neighborhood to the high-rise district of Atlantic Station in midtown Atlanta. But it continues to demonstrate its commitment the place where it was born.

It was there — across the street from famous Paschal’s Restaurant, just down the road from esteemed historically black institutions such as Spelman, Clark and Morehouse, and under the shadow of the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium rising next to the Georgia Dome (where, yes, Russell is involved work there too) — that an enthusiastic crowd of 50 community and business leaders gathered on January 12 to welcome U.S. Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Economic Development Jay Williams and the Minority Business Development Agency’s National Director Alejandra Y. Castillo to celebrate the renovation of the 40,000-sq.-ft. former HQ to become the Russell Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (RCIE).

In November 2016, RCIE received $3 million from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA) to fund the design and renovation of the existing building to house the center, located in an area designated as an official Promise Zone community by the federal government. The funding is part of 22 awards totaling $14.4 million from EDA to increase economic activity in the nation’s high-poverty urban, rural, and tribal communities.

“This is really a legacy for my father,” said H. Jerome Russell, RCIE founder and board member, describing Herman Russell’s incremental expansion of the building over 60 years and accompanying acquisition of real estate nearby. “He would tell us, ‘This is going to be part of downtown in the future.’ And it’s happened. He also believed in entrepreneurship — this building has always been an incubator,” helping small businesses grow and advance over time, he said. “We want to eliminate barriers to all, from college students with a brilliant business idea to the retired person launching their next passion in life. We believe RCIE will equalize the playing field in Atlanta and beyond by helping minority entrepreneurs, in particular, overcome barriers to entering the marketplace.”

The goal is for the complex to provide space for dozens of entrepreneurial firms, particularly in sectors that mesh well with the company’s longstanding areas of expertise: real estate, construction, food and beverage, and finance. Noting that the Russell family is the largest shareholder in Citizen’s Trust Bank, H. Jerome Russell said, “We’re going to form partnerships around those industries. We want to aggregate our influence and build entrepreneurs. We want to recreate the spirit in this building around what we have built. We’re going to partner with the university systems — we’re uniquely positioned in Atlanta because we have 60,000 to 70,000 graduates and undergrads within a one-mile radius, and 25,000 African-American graduate and undergraduate students here. We’re going to take all of that energy that’s here and partner with other organizations that can help us aggregate what we’re doing. You’re going to see it happen in 2017. Atlanta is on fire right now. I’ve lived here all my life, and this is unprecedented. And I think we’re in the early stages of it.”

Pathways Forward

While most of the building is under renovation, KIPP Metro Atlanta Schools — the area’s Knowledge Is Power Program charter school designed to serve students in underserved communities — moved into the building’s third floor last fall.

In his remarks, Williams noted how rare it was to step away from the all-important presidential transition in Washington just eight days before the inauguration. But this occasion warranted stepping away from packing up the office in order to further an all-important mission that transcends politics.

“The vast majority of efforts of federal agencies are geared toward making the transition as smooth as possible,” Williams said, standing before a diorama depicting the accomplishments of Herman Russell and his companies over the decades. “That was the instruction from the president. He also instructed us, though, that we should run through the tape, particularly with underserved communities. We will work until January 20th at 12 noon.”

(Williams’s role since January 20 is being filled on an interim basis by Tom Guevara at EDA. Williams, who once served as mayor of Youngstown, Ohio, is reported to be mulling a run for governor in that state. Asked about his plans in an interview after his remarks in Atlanta, he said he was considering a number of opportunities that might allow him to “move the needle.” Asked about working with the Trump transition team, he described them as “very professional, and very inquisitive and receptive. They have expressed a lot of interest about the EDA, and that is a very positive thing. I can tell you from the conversations I’ve had, I am encouraged. And I believe the EDA is well positioned to be an asset to the incoming administration.”)

Williams said he wanted pocket-sized cards of the company history depicted behind him “so I can show my six-year-old son and say, ‘This is ultimately where I want you to go, the pathway I want you to follow.’ “

“I was born and raised right here,” said Atlanta City Council President and candidate for mayor Ceasar Mitchell, a Morehouse graduate. “This physical piece of ground has been a place where leaders and business people have matured. I think about the many construction professionals, developers and folks in the financial industry who got their start under the tutelage of Herman Russell. This center will be able to take someone who has an idea, and help them incubate that idea into something that has reality, not just for personal prosperity, but to really change this community.”

“The opening of this center is a significant step in not only growing the pipeline of innovation-driven entrepreneurs, but also in developing strategic partnerships that will benefit our minority business communities,” said Castillo. “We need even more of these centers across the nation to help prepare the next generation of minority entrepreneurs and innovators for success in the 21st century economy.

“You didn’t have to donate this building,” she said to the Russell family members present. “You could have sold it. That means a lot. The challenge to all of you is that this $3 million is important, but this will take intellectual capital, partnership, commitment, time, and your contribution and engagement … because the Russells can’t do this alone … We don’t want this to just be an event. It’s what puts the marker down.”

“This is a huge project for us to take on in the midst of trying to run our operating businesses,” said Donata Russell Ross, founder, RCIE, RCIE board member and CEO of Concessions International. “But it’s so important to this community and the future of our young people, we just couldn’t say no.”

Acknowledging the grandchildren of Herman Russell in the room, she added, “This is something we’re leaving for them to continue, and for their children … This is not about the Russell family, it’s about the future of our community. We need environments like this to nurture and develop. When I was growing up, our father would always talk about looking back, reaching back and pulling those behind ahead. My hope is as generations come, they’ll not only hear these stories, but the walls will vibrate with these stories, and we all can create an environment where we can pull others forward.”

Long Tall Drink of Water

Another part of West Side Atlanta welcomed its own innovative infrastructure in September. Only this project involved $3 million times 100.

That’s how much the City of Atlanta’s Watershed Department is investing in a new 2.4-billion-gallon water supply reservoir at Bellwood Quarry, where rock that helped build modern Atlanta was mined. The big hole in the ground, located not far from Norfolk Southern’s intermodal yard, also carries vestiges of oppression related to prison chain gang labor and its connections to the 13th amendment to the US Constitution, which prohibited slavery except when punishment for crime (including the hazily defined crime of vagrancy) was involved. The city took over the reservoir in 2006. Most recently, it’s been the site of shoots for some film and TV programs, including the award-winning Stranger Things, The Hunger Games and The Walking Dead.

While the State of Georgia and its neighbors continue their battle over water rights (a tussle that ultimately will be decided by the US Supreme Court), Atlanta’s not waiting around for the verdict. That’s because the city only has a three-day water supply. “Once this $300 million project is complete, we’ll have a minimum of 30 days, ensuring that our residents and businesses have access to clean, safe drinking water for the next 100 years,” says the department’s website.

The reservoir is expected to be completed and filled by the end of 2018. As it happens, H.J. Russell & Co. is part of a joint venture with PC Construction that serves as construction manager at risk for the water supply program.

The reason for the September ceremony? To announce, after a fanciful contest, the official name for the 12.5-ft.-diameter, $11.6-million tunnel-boring machine now boring like a mechanical earthworm a five-mile tunnel to connect the quarry with the Chattahoochee River and the Hemphill Water Treatment plant. The reservoir will be the centerpiece of a larger park and recreation area.

Standing alongside the drill was Leonard Markley, a nine-year veteran of Robbins, the company that built and operates the drill. He and the crew had been building the 12-ft.-diameter machine for two-and-a-half months. But he’d seen bigger: The drill Robbins assembled for a major water tunnel near Niagara Falls was 52 feet in diameter. “The last six machines I’ve worked on haven’t been smaller than 20 ft. in diameter,” he said of two projects in San Francisco and four in Mexico digging tunnels for a subway and for wastewater.

Some cities, it seems, have bigger problems than Atlanta. Markley cited the four projects he worked on in Mexico. “Mexico City is sinking five inches a year,” he said, so the tunnels are being used to move the water out.

In an interview, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed said, “The water feature at the center of the city will spur economic development. You’ll see a three-to-one or four-to-one return on investment. “

Businesses also are attracted to places that plan and execute on the fundamentals with foresight instead of reactionary panic, he said, calling the new water source and park an important asset for the region. “Businesses and residents will be attracted to places that didn’t wait” for a crisis to precipitate action, he said. “No serious person can dispute that water will be an important resource. This gives the market confidence, and is a clear sign of the public getting a return on investment. It shows affirmative steps to deal with challenges. Reservoirs will be part of a long-term solution no matter what the resolution of the Supreme Court case is. There is a lot of chatter. This shows we’re not waiting.”

‘A Place of Power’

Department of Water Commissioner Kishia Powell, an 18-year veteran in water system administration with experience in London, Baltimore and, most recently, Jackson, Mississippi, put the project in context in her remarks, calling it a “crown jewel” project that, in its own earthbound way, will change the city’s skyline, in addition to adjusting its risk profile.

“Our nation’s capital only has a 36-hour water supply,” she noted, while Atlanta’s project is designed to help Atlanta sustain an abundant water supply even in times of drought and water crisis. “Two-thirds of the state is under severe drought conditions. We know the effects of climate change will only make it more challenging in the future. Atlanta is taking a proactive stance. We supply drinking water to more than 1.2 million people every day, including to Coca-Cola. This will increase the reserve from three days to between 30 and 90 days of water.” Moreover, she said, the city’s water system dates to 1875, and some of its raw water pipelines date to 1893, “so it’s time for a new tunnel.”

In an interview afterward, Powell noted, “The city would lose $100 million a day” if the backup reservoir were not there in the case of a water emergency. “It’s importance centers around resiliency, the ability to rebound from shocks and stressors.” She had just returned from a major conference focused on resilient cities. “We see the effects of not investing in water infrastructure for a long time,” she said, highlighting the water contamination disaster in Flint, Michigan. “The mayor is intent on making sure Atlanta’s future is sustainable and resilient. I am just honored and privileged to lead the department at such a pivotal time. There are not many cities making investments on this scale.”

The name chosen for the drill? From 700 submissions including “Scarlett” and “Peach Beast,” the winning entry, submitted by Georgia Conservancy Senior Director of Development and Marketing Brian Schroeder, was “Driller Mike,” after Atlanta hip-hop artist and social justice activist Michael “Killer Mike” Render, 40, part of the group Run the Jewels. Reed said the affiliation was not only “hot with the hipsters” in Atlanta’s smoking hip-hop scene, but emblematic of “all the tough digging work ahead.” Schroeder took the opportunity to champion such investment in underserved communities, and “the grind” of working on behalf of vulnerable populations. The music of Run the Jewels, he said, was “music about carrying on, about the grind.”

Render himself, who went to Collier Heights Elementary School nearby and owns a barbershop not far away, was on hand, taking the lighthearted gesture in stride while also saluting the project’s significance.

“I’m from about eight intersections that way,” he said, “so I knew how to get here pretty well. I have won a lot of trophies in my career, including a gold album, but never anything this … big,” he joked. “It’s partly satirical, but I’m really honored by my city, which is hard to do because we have potty mouths. People tend to not see the validity in rap, in black men, and in poor people,” he continued. “I have been all of those three. This is a testament to you and to what this country and this world could be. I encourage us to stay the city too busy to hate, but slow enough to engage each other in love. I want us to take time to say hello in the streets.

“I appreciate our city council, and state legislators, for showing Atlanta is a better place,” he continued. “I don’t ever want to cry for Atlanta like I’ve cried for place like Flint. Water is a right that people deserve. This is an equitable distribution of water. I drink it out of the tap, so that matters to me. I’m proud of Atlanta because we will always talk from a place of power.”

In an interview between selfies with his fans, I asked Render about the quarry’s legacy of oppression and 13th Amendment-related suffering.

“Evil and death have happened here,” he said. “Black people long have suffered in Atlanta, Georgia. Our story has built this country, built it for good and bad. But water is a conduit for life. The introduction of water and goodwill here can transform it. We wipe it out, but we don’t forget.”