W |

hen Boeing Co. touches down in Chicago and opens its new headquarters on Sept. 4, the world’s largest aerospace firm will teach corporate asset managers everywhere a valuable lesson: Don’t be afraid to leave home. Rather, base every real estate decision according to how your company is structuring itself for the future.

Boeing CEO Phil Condit made such a decision on March 21 when he announced that the Fortune 15 conglomerate would leave its 1916 birthplace of Seattle for one of three U.S. cities — Dallas, Denver or Chicago. Less than two months later, Condit told the world that the Second City finished first.

But there’s more to Boeing’s flight from the Pacific Northwest to the Great Lakes than a complex, yet amazingly quick site-selection drill. Underlying the move of the US$57 billion company is a business strategy designed to remake Boeing into an entirely different organization from the one Condit joined 36 years ago as an aerodynamics engineer.

When Condit announced the Chicago relocation at a Midway Airport press conference on May 10, he said that he wanted to distance the company’s headquarters operations from its operating divisions and focus the headquarters’ energies on new business lines and long-term growth. “We intend to do no less than define the future of aerospace,” he said.

In short, Boeing is not “your father’s 747 anymore.” It is a global company committed to increasing shareholder value by growing every business unit — from commercial airplanes to space to military aircraft — and a number of new ventures.

The only way to do this, say the company’s senior managers, is to cut the apron strings to Seattle and set up shop in a major financial market that’s pro-business, centrally located and equipped to propel Boeing’s diversification.

For Boeing, that place is Chicago.

From Seattle to Chicago: The Insider’s View

No one had a better insider’s view into Boeing’s headquarters search than Phil Cyburt, president of Long Beach, Calif.-based Boeing Realty Corp. As Boeing’s top real estate executive, it’s Cyburt’s job to make sure that the parent company’s boardroom strategy is implemented in physical workspace.

No one had a better insider’s view into Boeing’s headquarters search than Phil Cyburt, president of Long Beach, Calif.-based Boeing Realty Corp. As Boeing’s top real estate executive, it’s Cyburt’s job to make sure that the parent company’s boardroom strategy is implemented in physical workspace.

For a company that owns 124 million sq. ft. (11.5 million sq. m.) of property assets valued at $9 billion, that’s no easy task — especially when the parent expects its space needs to be met in weeks, not months.

“Doing the corporate headquarters transaction in seven weeks was one of the most difficult things I have done in my career,” says Cyburt. “Boeing is a brand name, and this is like moving General Motors out of Detroit. This is a big change for the Boeing Co.”

How big a change? Consider the magnitude of Boeing’s economic impact:

- Every 777 airplane the company builds uses 4 million parts and 26,000 suppliers.

- Over the next 24 hours, the Boeing spare parts Web site will complete 18,000 transactions, with sales topping $1 million.

- Boeing employs 198,000 people in 62 countries, including 78,000 workers in the Puget Sound region of Washington.

- Boeing controls more office and industrial property than Sam Zell, Chicago’s best-known owner and developer of institutional real estate.

- Boeing Capital — the company’s financial arm that’s launching new debt and equity products — is expected to grow to six times its current asset base within five years.

Compared with numbers like those above, moving an executive headquarters facility of 500 people doesn’t seem large at all — until you realize what’s behind the move.

“It’s a strategy to reorganize the entire company and carry the Boeing name globally,” Cyburt says. “Boeing is redefining aerospace. It’s not only things that fly. It’s things that fly wireless. We are a technology company, as evidenced by our new Connexion by Boeing telecommunications unit, which is developing high-speed voice and data transmission networks for people doing business 30,000 feet above the earth. Few other companies in the world have more intellectual capital than this one.”

Cyburt says his No. 1 challenge is to “stay in front of that technology” by making Boeing’s real estate operation move as rapidly and run as efficiently as the parent company.

Matching the speed of Boeing won’t be easy. The company’s goal for its commercial airplane group is to cut in half its current average time from plane order to delivery through a system called “lean manufacturing.” The firm plans to eliminate waste, reduce factory space and cut down on unnecessary inventory.

Boeing wants to avoid another year like 1997, when it tried to increase its production by 100 percent but encountered severe parts-supply problems and worker shortages. The woes forced the company to temporarily halt all assembly work on the 737 and 747 lines.

Even though Boeing finished 1997 by selling a record $24.5 billion in commercial planes, the division lost $1.6 billion and, more importantly, several customers to arch-rival Airbus Industrie of Europe.

A Web-based procurement system plays a key role in Boeing’s lean manufacturing plan. The system allows parts suppliers to track the planemaker’s schedule 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and provide new parts as needed. Other plan components include the adoption of more standardized parts and procedures and a series of “feeder lines” — mini-assembly lines where various parts are pre-assembled before being installed in the aircraft.

Streamlining production cuts costs for Boeing by reducing the number of workers needed to build a plane and the amount of floor space required for assembly. Condit has talked about reducing production costs by as much as 50 percent.

On March 21, the CEO said he believed Boeing could significantly reduce “the number of parts you use to build an airplane, so that changes what you want to make and how you assemble aircraft.” Condit added that the company would assess which manufacturing jobs “outsiders can do better.” His goal? Free up Boeing workers and facilities “to focus on the higher-level issues” like integrating digital wireless networks into Boeing planes.

Goal: Reduce Space by 25 Percent

It hasn’t taken long for Condit’s “lean” strategy to impact the company’s payroll and facility base. Over the past three years, Boeing has reduced its commercial airplane work force by 25,000 people and its company-wide work force by 49,000. The company also decided that some assembly work can be performed better, and more cost-effectively, outside the state of Washington.

In August 2000, Boeing decided to close two Seattle area plants and shift about 1,000 workers to other jobs. The move affected a small parts factory near Mukilteo and a machine shop in Kent. Boeing also said it would consolidate portions of its operations in Auburn.

On March 23, 2001, Boeing announced that it would transfer fabrication of fuselages for 757 jetliners from Renton, Wash., to Wichita, Kan. While the decision affects only 500 jobs and is not expected to result in many layoffs, company executives say the move could be a precursor to more sweeping plant location choices and labor force decisions.

On May 25, Boeing’s Long Beach plant announced a layoff of 600 workers. The Southern California factory builds the Boeing 717, which has experienced declining sales in recent years. The 717 was inherited from the former St. Louis-based McDonnell Douglas. The Long Beach plant employs 5,000 people. The company said that all job categories would be affected by the work-force reduction.

The long-term strategy of work-force and workspace reduction is to trim Boeing’s 124 million sq. ft. (11.5 million sq. m.) of inventory by 30 million sq. ft. (2.8 million sq. m.), says Cyburt. “The key target of Boeing’s asset utilization initiative is to get the size of the portfolio down,” he explains. “By downsizing our space needs, our projections show that we will free up an additional cash flow of $12 billion over the next three years.

“In the aerospace model, you have a lot of assets driving slim margins,” Cyburt adds. “We do a financial pro forma on each business line Boeing operates. We ask, what are my revenues and what are my margins? We find out where the value-add is and where we’re generating negative returns. We try to outsource those assets that are giving negative returns. Our long-term goal is to reduce the assets that are driving the revenues for Boeing.”

Structured as a subsidiary, Boeing Realty fulfills two roles for the parent company. It manages all corporate real estate needs and seeks to maximize the value of surplus property. “Any property that is surplus and has a value-add element to it moves over to our development portfolio,” Cyburt says. “Our entire development portfolio, including land and buildings, is about $2 billion. If we were structured as a REIT (real estate investment trust), we would be one of the largest REITs in the country.”

Like Boeing’s corporate real estate, the company’s development portfolio is a diverse mix of class A office space, research and development facilities, business parks, warehouses and factories. One of the company’s largest development projects is the 240-acre (97-ha.) Pacific Gateway Business Park in Kent, Wash. A development of surplus Boeing land, the property is next to the Boeing Space Center along West Valley Highway.

“Pacific Gateway represents a rare opportunity for corporate users or developers to build and own their own real estate within a premier master-planned business park,” says Cyburt. “To insure sustainability and protect investment value, we have instituted high-quality architectural and design guidelines.”

The park, which has entitlements for 2.4 million sq. ft. (223,000 sq. m.) of office and industrial space, is one of 50 development projects spearheaded by Boeing Realty since 1996. To date, Boeing Realty has developed 7 million sq. ft. (650,300 sq. m.) of commercial space and brought 1,000 acres (405 ha.) of mixed-use development to the market.

Boeing Realty: The Corporate Role

Cyburt’s dual role — manage all real estate assets for Boeing; sell off or develop excess space — is driven by Condit’s three-pronged strategy to diversify, decentralize and downsize. As Boeing gets both leaner and more global at the same time, Cyburt faces the challenge of managing assets in places as close as Long Beach and as far away as Brisbane, Australia. Major corporate hubs in the U.S. include operations in Renton, Everett and Kent, Wash.; Long Beach, Calif.; Houston; Wichita, Kan.; and St. Louis, Mo.

Cyburt’s dual role — manage all real estate assets for Boeing; sell off or develop excess space — is driven by Condit’s three-pronged strategy to diversify, decentralize and downsize. As Boeing gets both leaner and more global at the same time, Cyburt faces the challenge of managing assets in places as close as Long Beach and as far away as Brisbane, Australia. Major corporate hubs in the U.S. include operations in Renton, Everett and Kent, Wash.; Long Beach, Calif.; Houston; Wichita, Kan.; and St. Louis, Mo.

The only way Cyburt can manage such a vast portfolio, he says, is to act as “a manager of a network of service advisors.” Whether the job requires selecting a site for a new corporate headquarters in Chicago or leasing 160,000 sq. ft. (14,800 sq. m.) of new office space for the company’s Airplane Services Division in Issaquah, Wash., Cyburt must rely on a number of key service providers.

A key player on this team is Ernst & Young, which provides a variety of advisory services for Boeing Realty. “Boeing Realty consults with us on strategic issues with respect to marketing, strategies for development and joint venturing of properties — general real estate advisory work,” says Greg Gotthardt, principal, who with colleague Steve Duffy works closely with Cyburt. “There’s no one way to characterize the type of work we do with Boeing Realty.”

Part of why Gotthardt says he enjoys working on the Boeing account is because “it is one of the more fluid organizations we work with.” Cyburt’s group is particularly good at disposing of surplus real estate in such a way that maximum value is realized, he adds. “They are willing to work harder and spend more time on that, whereas other corporate clients’ view is to just move that property off the balance sheet,” Gotthardt relates.

Another service provider — Mike Hubbard, senior vice president and principal at Trammell Crow — puts it this way: “In this portfolio, there are opportunities to affect real estate strategies that create shareholder value. Finding the opportunities and matching the real estate strategies with the business and operating strategies is the trick,” he says.

“The service providers are the people on the ground who are the experts on the local market. Their job is to take a lot of the pre-tactical work out of our shop so that we can focus on strategy,” says Cyburt. “We have the service advisor go out and gather the data wherever we need it. In the Puget Sound region, we use Trammell Crow. In Southern California, the Midwest and the East, we use CB Richard Ellis. My department could be over 100 people easily, but we have been able to leverage the service provider to get a better product for our customer.”

A case in point is the headquarters relocation. While Condit would make the final decision, Boeing Chief Administrative Officer John Warner chaired the site selection committee. Cyburt oversaw all aspects of the real estate side of the deal. Ernst & Young negotiated tax incentives, provided financial analysis and gathered all data on Dallas, Denver and Chicago. Cushman Realty Corp. in Chicago worked on the deal as Boeing’s tenant representatives. Callison & Associates in Seattle coordinated interior workspace design and layout. Turner Construction, as general contractor, managed the buildout.

of World Business Chicago led the economic development campaign.

While Warner directed the strategic aspects of the site search, Cyburt made sure that all service advisors fulfilled their role. When negotiations for a 15-year lease at 100 North Riverside Avenue on the Chicago River hit an eleventh-hour snag, Cushman Realty persevered through frantic all-night negotiations to close the deal.

In order to finalize the transaction on the 280,000 sq. ft. (26,000 sq. m.) of class A office space being vacated by Philadelphia-based Rohm and Haas, owners of Morton Salt International, negotiators needed the help of the city of Chicago. Mayor Richard Daley stepped in and pledged $1 million to help buy out the Morton lease and let Rohm and Haas walk away.

Built in 1989, the 770,000-sq.-ft. (71,500-sq.-m.) skyscraper in the West Loop of the Chicago central business district was purchased in December 1997 by a Florida state pension fund whose assets are managed by Lend Lease Real Estate Investments. Boeing will occupy floors 25 through 36 and bring the building’s occupancy to nearly 100 percent. (Cyburt told Site Selection in July that about 250 of the 500 Boeing executives in the home office had opted to remain in Seattle.)

Boeing reportedly will pay market-rate rent of $20 per square foot during the agreement’s first year, with rent increasing 3 percent per year. Boeing estimates its interior buildout costs at $30 per square foot.

The very design of the building Boeing chose to be the new headquarters helps convey a sense of technology and speed, both of which are key ingredients in the company’s recipe for future success. Mark Ludtka, a principal at Seattle-based architecture and design firm Callison & Associates, helped evaluate the 20 locations that made the short list in each of the three cities Boeing considered. “One Hundred North Riverside Avenue is a well-engineered building with great detail,” he relates. “It looks like a tower for a technology company.”

Ludtka’s team is considering ways to bring inside the tower manifestations of the high-tech culture Boeing is implementing as well as new thinking in work-space design. “We are working with Boeing on reassessing the work place and determining how to create a more collaborative environment that ultimately will help them streamline the process of getting idea to generation to implementation faster. In time, that is a role the work place will play for Boeing.” In the meantime, Ludtka’s task is to prepare the interior for the soon-to-arrive employees by putting in place the infrastructure that will let them hit the ground running.

How the Windy City Won Boeing

Since the May 10 announcement that Chicago beat Dallas and Denver, experts have speculated on what sealed the deal for the Windy City. Some speculated that it was the city’s cultural diversity. Others suggested Chicago’s thriving urban arts and entertainment. Still others said it was purely about money.

In the final analysis, however, several factors proved pivotal in landing Chicago a tenant Arthur Andersen says will generate $4.5 billion in economic impact over the next 20 years. Foremost was Chicago’s pro-business philosophy, manifest in everything from its $63 million state and local incentive package to its willingness to do whatever it took to close the deal.

In Washington State, Boeing often encountered resistance from state officials when the company wanted to expand. As recently as October 1999, a top Boeing executive warned Washington that the company’s future expansions could be headed elsewhere if the state did not improve its business climate.

“Compared to everywhere else we do business, Washington is below average,” said then-Boeing CFO Deborah Hopkins. “To remain a global leader for aerospace — and a global leader for other industries — Washington has to rank a whole lot higher than that. We want to grow our operations here in Washington, but we’re simply not in the most beneficial place in which to do business.”

Contrast that with Chicago. In addition to the personal involvement of Illinois Gov. George Ryan and Mayor Daley, the city granted Boeing a waiver from an ordinance prohibiting company logos on the top of buildings.

To Boeing Chief Administrative Officer Warner, the pro-business attitude in Chicago meant much more than the financial incentives. “As we looked at the total cost issues, it (the incentives package) became an irrelevant point,” Warner said in May. “As we looked at it in the long-term scheme of things, we said this (incentives) is not a major factor.” Of greater importance was the capacity of state and local leaders to work together to facilitate Boeing’s move.

“Clearly, it’s how people treat business,” said Warner. “It’s something that sends signals for a very long time.”

Paul O’Connor, executive director of World Business Chicago, says that his economic development team adopted “the Ford Strategy” — a reference to his city’s successful recruitment of a major Ford plant last year — to win Boeing. “That strategy is to win every point, give them your best shot right out of the box, and create such a wave of momentum that the competitors will be overwhelmed,” says O’Connor. “That strategy paid off.”

A second crucial factor is the access Chicago gives Boeing to global financial markets. With 35 Fortune 500 companies, 300 U.S. banks, 40 foreign banks and five major exchanges, Chicago ranks second in the world to New York as a financial center. Chicago’s regional $304 billion economy would rank 19th in the world, just behind Argentina and ahead of Taiwan.

The third, and perhaps, deciding factor, is Chicago’s central location — the closest to New York of the three finalists and yet only a half-day’s travel time by air to Seattle, where Boeing maintains most of its operations. When your company CEO spends 80 days of the year traveling in the air, as Condit did last year, it pays to move him closer to the places where deals get done.

A recent Arthur Andersen study showed that company performance is improved when key executives are “able to facilitate critical transactions.” Last year, Condit received more than $15 million in total compensation ($1.4 million in salary; a $2 million bonus; and a $12.1 million payout under a long-term incentive plan tied to the company’s stock price). In real dollars, it makes sense for Boeing to have its highest-paid executive on the ground as much as possible.

Other factors played a role in Chicago’s victory, says O’Connor. Among them were Chicago’s air transportation infrastructure (O’Hare and Midway); advanced telecommunications networks; big-city quality of life; diversified human capital that emerges from a diversified economy; affordable cost of housing; access to engineering graduates and MBA’s from nearby colleges and universities; and an urban core that does not shut down at 6 o’clock every evening.

Ultimate Target: $4.7 Trillion Pie

The next challenge for Condit is to lead a company to outpace its record $57 billion in revenues this year and experience even greater returns from its airplane manufacturing division. Boeing bolstered Wall Street analysts earlier this year when it reported first-quarter operating margins of 10 percent for the first time in a decade. Condit also hopes to double the revenues of Boeing’s space and communications unit in the next five years. Last year, the division’s revenue climbed 18 percent to $8 billion.

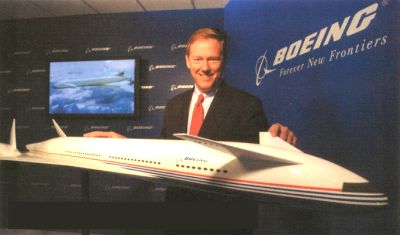

Today, Boeing is exploring a 757/767 replacement aircraft that can fly at Mach 0.95, faster than any current Boeing plane. “We are developing designs that would reduce flying time as much as 15 to 20 percent while achieving ranges not possible with current airplanes,” says Condit. “We have identified a set of cost and performance technologies that will allow the design of a radically different airplane.”

At the Paris Air Show earlier this summer, Boeing wowed the crowds by unveiling the next-generation design of its “sonic cruiser,” designed to help airlines achieve substantial time savings by adopting point-to-point operations. Boeing also released its 2001 Current Market Outlook at the air show, noting a forecast of a $4.7 trillion market for new commercial airplanes and aviation services over the next 20 years.

Moving Boeing’s headquarters from Seattle to Chicago not only reflects Condit’s global strategy to diversify, decentralize and downsize. It positions Boeing to capture the biggest piece of that $4.7 trillion pie.

Continue to: Special Web-only Bonus Section