The unique climates and business climates of western North Carolina, central Oregon and Washington, Northern Virginia and Iceland are providing the most bang for the buck for major data center projects, which are being announced at an unprecedented pace. Where companies and their data services providers go next hinges on such factors as disaster risk; latency; broadband infrastructure; cost and availability of power; and the increasingly relevant size of carbon footprints.

At the Advania Thor Data Center outside Reykjavik, Iceland, power from both hydroelectric dams and geothermal plants has kept the facility’s carbon footprint at zero, while also staying affordable — Iceland’s average cost of electricity is approximately 20 percent less than the average across the 27-country European Union.

Speaking of zero, “natural free cooling, amply provided by Kári (an Icelandic nickname for the wind), is used to control temperatures inside the data center, and helps to keep costs down,” says the company’s website. “The average temperature at the data center location is 1.8°C in January and 10°C in July.”

Moreover, the location midway between Europe and the United States means minimized bandwidth usage and network latency: Iceland is connected to the world by three sub-sea cables that function together as a single system linking the nation to Scotland, Norway and Nova Scotia, Canada. “The utilization on these cables is low and the bandwith is plentiful,” says the company.

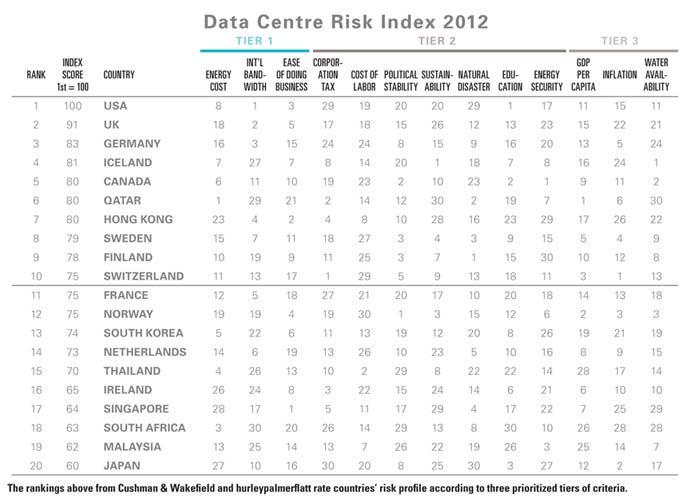

Those conditions are why Cushman & Wakefield and consultancy hurleypalmerflatt’s Data Centre Risk Index 2012 report, released in April, added the Nordic nations of Norway, Finland and Iceland (along with seven others) to the previous index’s total of 20 nations. They also added to the index the factors of energy security and education. (See the rankings chart, as well as scores by variable).

The rise of the Nordics comes as Google has located in Finland and Facebook in Sweden. Iceland ranks highest among the Nordics. Switzerland ranks 10th primarily due to low risk factors, low inflation and low corporate taxation. Such factors explain why ABB and ICT service provider Green on May 30 announced the opening of Green’s new Zurich-West data center expansion based on direct current (DC) technology. Green’s facility, which employs HVDC-capable HP servers, is the most powerful application of DC in a data center to date.

“Performance tests showed that Green’s new power distribution system is 10 percent more efficient than for comparable alternating current (AC) technology,” said a news release. “In addition, investment costs for the system were 15 percent lower than for an AC system,” and DC systems, it says, require as much as 25 percent less space, and reduce equipment, installation, real estate and maintenance costs.

Those percentages can come in handy when nearly 6 million servers are coming online annually and data center energy demand is increasing by more than 10 percent a year.

Cool Only Goes So Far

Speaking by phone from his London office, Keith Inglis, partner in the EMEA Data Centre Advisory Group at Cushman & Wakefield, says the Nordics have become increasingly attractive by the simple virtue of their cooler air and improved energy efficiency, which supports sustainability objectives while also boosting their brand images as lovers of the planet. “In a sense, cooling and the climate is the driver for certain players,” he says. In fact, three of the 10 new countries introduced this year make the report’s top 10.

But Inglis is quick to point out that no matter how much sustainability rises in weighted importance, “the bottom line is occupiers are going to be driven by commercial need first and foremost. Some countries say, ‘Why are we so low?’ I turn around and say commercial drivers are going to dictate where the client is going to go. If customers are in Qatar, they need to be accepting of the fact that Qatar does not score well on, for example, bandwidth, and clearly is going to score low on sustainability, since nearly all power is generated by the oil industry.”

Inglis buttresses his argument with an observation he gleaned from a recent data center conference, where he learned that while some 85 percent of companies have a sustainability program, less than half those companies are applying its principles to data center deployment.

“It’s a potential PR disaster,” he says. “Data centers need to draw from sustainable sources … they account for between 1.5 percent and 2 percent of emissions.” People are increasingly concerned about it, but again, he says, “it doesn’t stop them from going to where the infrastructure exists to support the data centers in the first place. It’s a difficult balance to capture.”

In the Asia Pacific, Inglis points to South Korea as one to keep an eye on, because “it has a government that’s investing in a knowledge economy.” Asked about Australia’s relatively low ranking, given its high-profile digital economy strategy and national broadband rollout, he says the rollout is encouraging, and more data centers are indeed popping up, especially in Sydney. By comparison, he says there’s also a broadband rollout afoot in China: “500 million people connect in five years is their plan,” he says.

Commercial Needs Prevail

Asked if he sees evidence of data centers as economic development harbingers for other projects such as shared service centers and IT and software R&D centers, Inglis says, “If anything, it’s the other way around. Data centers tend to grow around where the skill sets are already.”

Ultimately, says Inglis, a data center goes into a country for commercial purposes first and foremost. “A lot of people get bound up because of too many risks in India, for example, but India can still be nirvana.”

That may be the case for Tulip Telecom and IBM, which in February committed to building India’s largest data center in Bangalore to serve the country’s growing mobile consumer market. Covering more than 900,000 sq. ft. (83,610 sq. m.), and 20 Enterprise Modular Data Centers in a four-tower building, the facility is engineered to support up to 100 megawatts of power, making it the third largest data center in the world. IBM has designed and delivered more than 1,000 modular data centers for customers around the globe, and says it’s helped customers save up to 30 percent in energy costs per year compared to traditional data centers.

Asked about the importance of latency, Inglis says it’s most relevant to financial markets, but that 75 percent of the overall data center market is serving the opposite of lightning-fast speed: data storage, for content as trivial as all those digital photos from the holidays or as crucial as the data insurers require to be kept for a number of years.

“Those can go anywhere,” he says of the data storage facilities. “That’s why Facebook is going to Sweden. The latency argument goes out the window.” That said, one interesting development is the bracketing of synchronous replication operations with asynchronous in one big data center. “As soon as they do that, it needs to sit very close to the big Internet exchange points such as London or Amsterdam,” he says. “Our data center in London is 20 miles away. I want my emails coming up in milliseconds.”

Unprecedented Activity

Six years ago, global data center firm Equinix operated 17 data centers. Today that number is 21 in the U.S. alone and 18 more abroad, with several projects announced around the world since the beginning of this year alone. No wonder the company showed 105 job openings on its jobs Web page on May 15.

They’re just one of many trying to get their hands around the cloud, as big data, like an encroaching flood, threatens to outpace all efforts to contain it.

Gary Nagamori, a managing principal at HDR Architecture, says big data is pressing on existing infrastructure, as organizations struggle all at once with collecting it and putting it to use in research.

“Before they can even get to the cloud, most levels of IT I think are really struggling to provide for this explosion in data,” he says. “IT’s stressing out most IT networks, taking them to a point of unreliability. Ask the average CIO, and they’re quietly grappling with that now. There’s a need to really think about what a data center has to do, and therefore where it should be located. It’s no longer an issue of backup, it’s about using that data.”

Chasing all that data means a lot of territories are chasing data centers as a crucial cog in regional economic development. A check of legislative calendars around the U.S. will turn up a number of new measures such as the Alabama Data Processing Center Economic Incentive Act of 2012 and several statutory updates in Nebraska passed earlier this year.

A run through the major global real estate and AEC service providers ranging from CBRE and Jones Lang LaSalle to Structure Tone, IDI, Integrated Design Group and Russo Development will turn up a server’s worth of data about new data center and mission-critical real estate practices within their folds.

And utilities are doing all they can to appease the demand for their power while marketing at the same time: Witness Exelon’s June rollout of a new energy efficiency program for data centers in its Chicago territory, and the joint work by TVA and Deloitte to identify 12 sites in TVA territory (Bristol, Tenn., most recently) that are best suited for data center location.

Some go so far as to attribute the need for new power generation plants to the demand for power from the data economy. According to a recent press release from the Nuclear Energy Institute’s annual conference in North Carolina celebrating the thousands of jobs being created by new nuclear plants in Georgia and in South Carolina, Mark Mills, founder of Digital Power Group, said approximately $1.2 trillion of U.S. gross domestic product is associated with creating and transporting information, while only $500 billion is associated with transporting people or things.

Meanwhile, concurrent with the news that its innovative fuel cells would power Apple’s mega-data center in Maiden, N.C., California-based Bloom Energy in March announced the formation of its own Mission Critical Practice.

Hosted data center companies and REITs, as well as stand-alone projects, can’t move forward fast enough, whether it’s the incipient Steel Orca project coming together on former U.S. Steel property in Pennsylvania or the June announcement from CenturyLink firm Savvis that it would be opening or expanding centers at seven locations this year in Singapore, London (2), Santa Clara, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; Dallas; and Weehawken, N.J., bringing its total data center footprint to more than 2 million sq. ft. (185,800 sq. m.) in 50 facilities. The company also recently located a new German headquarters in Frankfurt.

The growing Equinix portfolio includes new projects, acquisitions or expansions in Zurich and Geneva, Switzerland; Sydney, Australia; Hong Kong; Shanghai; Singapore; Tokyo; Paris; Seattle; Washington, D.C.; and Dulles, Va.; and Boca Raton, Fla., which it plans to use as a jumping-off point to serve Latin America and Brazil’s World Cup and 2016 Olympics needs in particular.

Capital Crunch

A recent study of North America by data center REIT Digital Realty Trust (DRT) found that 92 percent of senior decision-makers on data center strategies at large corporations will definitely or most likely expand in 2012. The figure is 76 percent among decision-makers in the Asia Pacific.

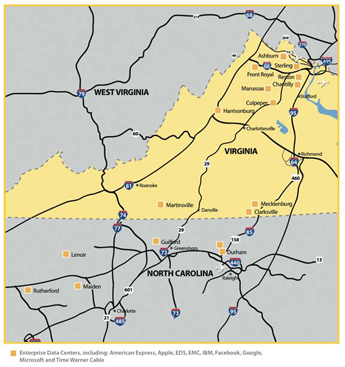

It’s no surprise to REIT watchers that DRT in May announced its fourth facility at its Northern Virginia campus in Ashburn, in Loudoun County, in the middle of what is probably the most data-dense corridor in North America and one of the densest in the world. Recent projects have also come to Ashburn from Equinix, RagingWire, Sabey and DuPont Fabros.

As the project tallies presented here illustrate, Northern Virginia and Greater D.C. are truly the leaders in data center attraction and expansion. A 2007 presentation from Dominion Chairman, President and CEO Thomas Farrell noted that PJM had predicted overall demand in Dominion’s service area would go up by 1,800 MW in the next five years. Five years later, his May 8, 2012 presentation noted that data center demand alone is projected to grow by 1,200 MW, and overall demand by 4,000 MW in the next decade.

Kent Hill, senior manager of economic development for Dominion Virginia Power, says the 24-hour load characteristics for data centers are similar to those of a large manufacturer, but such centers happen to be in locations where you wouldn’t find manufacturing, such as Ashburn in Loudoun County, Va.

But while the dense fiber and dense facility footprint is there, data centers also are going elsewhere in Virginia, such as Microsoft’s location in the south-central part of the state, and QTS’s purchase of the former Qimonda and Infineon semiconductor manufacturing facility in Richmond.

Asked about the importance of broadband infrastructure for cultivating a data center cluster, Hill calls it “absolutely critical,” noting the funding of such infrastructure by tobacco commission money in southside Virginia. “The Microsoft location would probably not have occurred without that infrastructure being in place,” he says, and other prospects are looking there for the same reason. A similar dynamic is at work in Ulster, N.Y., where Time Warner Cable Business Class and TechCity Properties recently announced the completion of an advanced communications fiber network to the 258-acre (104-hectare), 2.2-million-sq.-ft. (204,380-sq.-m.) TechCity complex near Kingston, N.Y.

Asked about Northern Virginia’s unique mix of government and private sector data centers, he admits there are likely some government centers that operate behind a meter served by Dominion, but aren’t necessarily sharing what they’re doing there. At the same time, “there is a fairly large federal data center consolidation process under way. We’re looking at how it will impact our region, and making sure we have sites and buildings that can accommodate that. We are also seeing some government facilities in co-location centers,” some of which are factoring government security standards into their designs and site selections. “That’s what’s nice about the Northern Virginia market — you have several options.”

Hill says since cost of power might represent between 20 percent and 50 percent of total operating costs at a data center, that’s still a big factor. But sustainability is getting bigger as the data gets bigger.

“All things being equal, if the price is the same, and reliability is similar, site selectors are going to pick the site with the lowest carbon footprint. That’s the message we’re getting,” he says. “Our generation mix puts us into the lowest third of utilities in terms of carbon intensity. But our approach is balanced between traditional sources and an increasing mix of renewables as they make sense from a cost-effectiveness standpoint.” He anticipates Dominion being ahead of the state’s renewable energy goal of 15 percent by 2025.

The more pressing timeline, he says, often is the one a data center project requires, with a large block of power attached.

“It’s caused us to change our whole planning model,” he says, with what would normally be a five-year timeline compressing to coming online in 12 to 18 months. “It’s changed how we plan and locate our substations,” he says. “Particularly now that the concept of modular data centers is out there, basically a mini data center can be brought in on a flat bed, connected to a power spine and you’re up and running. How quickly you can deliver a site and deliver the power are bigger issues particularly for some of the co-location companies, who may land a big contract in the course of a month or two.”

Count Virginia among those jurisdictions with freshly minted data center incentives too, says Hill, which primarily expands job number thresholds to garner tax exemptions. He says it was an issue for some co-location companies who were not getting credit for their tenants creating jobs.

“So that was amended to include tenants for that property so they get credit,” he says. “It’s a big issue for these customers. It’s very capital intensive and, depending on the company, they’re replacing servers and equipment every two to four years, so a sales tax exemption is pretty significant.”

Hill says the communities his department works with are all interested in attracting data center business precisely because of the improvements such facilities bring to the tax base. “We’re finding that even though the job count is not typically as high as you’d see in manufacturing, the tax benefits are substantial,” he says.

Similar dynamics are at work not far to the south in Kings Mountain, N.C., which has attracted data centers in the past two years from AT&T, Wipro InfoCrossing and Walt Disney Worldwide Services. As in Virginia, the cost of power is a big lever. So was the 2009 decision by Atlanta-based T5 Partners to develop the 260 acres (105 hectares) of Potts Creek Industrial Park, and bring the park into the city’s jurisdiction, where municipal incentives apply.

Wipro was the first to take advantage, choosing to locate in a former CrisCraft building. Disney’s project (with another phase planned) should be complete this year. And AT&T’s 500,000-sq.-ft. (46,450-sq. m.) first phase should be complete by 2014, bringing with it a $200-million investment and approximately 100 full-time jobs.

The facilities all will be served by Duke Power. But in Kings Mountain’s case, in addition to the tax base, the city happens to operate the area’s other utilities. The city should see a 12-percent increase in its utility revenue from the three data center projects alone.

“We’re just glad they’re here,” says Kings Mountain Mayor Rick Murphrey of the data center projects, noting his area’s fixed assets: significant water, sewer, gas and electric infrastructure left over from the textile era. He says the projects’ name recognition has led to better name recognition for his city, which will still collect a franchise tax while foregoing the city tax and some permit fees. Meanwhile, fiberoptic infrastructure is being installed around all municipal buildings, and the already substantial water infrastructure is being expanded still further.

Texas at the Top

It’s no surprise that four Texas metros are among the Top 10 areas since Jan. 2010 in our tally of data centers, nor that that activity drove Texas to the No. 1 spot among states.

CASE Commercial Real Estate Partners (the exclusive developer for the Mark Cuban Companies) and Synergy Renewables (an affiliated company of T. Boone Pickens) are developing the first data centers in the U.S. to use 100-percent green power based upon clean waste-to-energy technology and Texas wind generation. The data centers will be at Wonderview, Cuban’s development located not far from downtown Dallas.

The project was announced in October 2011. In April 2012, CASE announced it was launching data center advisory services in partnership with Amicus Partners. Leading the new service line are Jeff Crawford and Chuck Smith, managing directors, and Jim Mangus, senior director, who have combined over 50 years of operational data center experience. Smith’s 15 years in the industry have allowed him to observe the flocking of facilities to high-tech test beds such as Silicon Valley, Austin and Seattle during the tech boom, followed by outsourcing by end users, usually following Internet bandwidth to DFW, Chicago and New Jersey.

“Picture it as an evolution,” he says. “Chase the tech innovation, then chase the traditional Tier 1s. Then evolve into any major icity that has big Internet backbones — Atlanta, Denver. Then you see the colocation companies pop up in those cities.”

Thus, about five years ago, he says, companies started asking themselves the question, “If we don’t consume 3 megawatts of power, why are we in the data center business?” Companies then began outsourcing to a proliferation of wholesale data center providers. Though the backbone of site selection hot spots remains, he says now we’ll see companies, whether colocation firms or end users, moving into Tier 2 cities. The June announcement of a $15-million, 40,000-sq.-ft. (3,716-sq.-m.) colocation project from Involta in Tucson, Ariz., may serve as an example. Involta CEO Bruce Lehrman said the 600-cabinet facility would offer advantages to businesses in such areas as Phoenix and Southern California.

Smith says we’ll also see the rise of modular data centers, a hot topic at a recent conference convened by Uptime Institute.

“Company X wants to spread a data center across three or four different geographic locations, different climates and time zones, but you still have to buy by the kilowatt or sq. ft., and you’ll proabably end up buying more than you need,” explains Smith. “The thought process with modular is to accomplish exactly this — 3,212 square feet in this city, 18,000 square feet in that city. You can start doing that if you’re modular. The Uptime guys said there are 36 avowed modular/container providers and manufacturers now. The end user doing site selection now has flexibility. If I’d like to put 1,000 square feet in Phoenix and haven’t had the option, now I have it.”

Smith says modular is showing up in places that already have robust power: Phoenix-based modular data center firm IO is putting in about 800,000 sq. ft. (74,320 sq. m.) in Phoenix and about the same in New Jersey, “huge shells where they park modules,” he says, with the ability to have modules of different densities.

The benefit of the approach also accrues to the facility’s PUE, or power usage efficiency, as each modular container has its own.

Smith says a client recently stated a desire for 500 kilowatts of Tier-3 data center, a typical demand. Conversation revealed the client, in a perfect world, wanted 30 percent Tier 3 and 70 percent Tier 2 but “that doesn’t exist.” But with modular, it can be done.

“It’s on demand like virtualization is to servers,” says Smith. ‘I only want the data center I need’ — you’ll start to be able to do that, so theoretically it will drive down what the end user pays.”

It will also introduce new drivers to the site selection process. For instance, Smith says, a Fortune 500 company wants to put the data center in Ohio because its headquarters is there.

“Well, there’s no Digital Realty Trust or DuPont Fabros there, but a modular company can go there on behalf of that Fortune 500. Site selection used to be so clean, right? Now, if a Fortune 500 tells you, ‘I’d prefer two megawatts of data center in Abilene, Texas, it can be done. And it may take utilities a bit out of the driver’s seat.

“Take a state that’s deregulated like Texas,” he says. “You can move around a little more freely if you’re deploying modular solutions versus a big campus data center.”

In more general terms, says Smith, his team is seeing a future where there’s less competing for data centers between states, and more competing among cities of various sizes. In Texas, Farmer’s Branch is competing with Dallas. In California, Santa Clara has successfully gone toe to toe with San Jose.

Asked if such areas are seeing IT services, back-office and other spinoff from their data center activity, he diverges from Inglis of Cushman & Wakefield and says, “Without a doubt. It’s probably one of those intangibles that doesn’t get reported on enough,” citing Santa Clara and Richardson, Texas, as examples. His team currently is consulting to a project linking high-performance computing projects between Canadian universities and the U.S. “They’re even talking about allowing commercial data centers to be built on a university’s land,” he says.

In another case, Smith says, “We met with a city last week, and they said, ‘Here’s land and incentives.’ I asked ‘What do you think you’re gaining?’ They’re aware it’s not jobs. And if they’re giving away tax revenue, they understand. They believe it’s a big lure to attract traditional brick-and-mortar companies.”