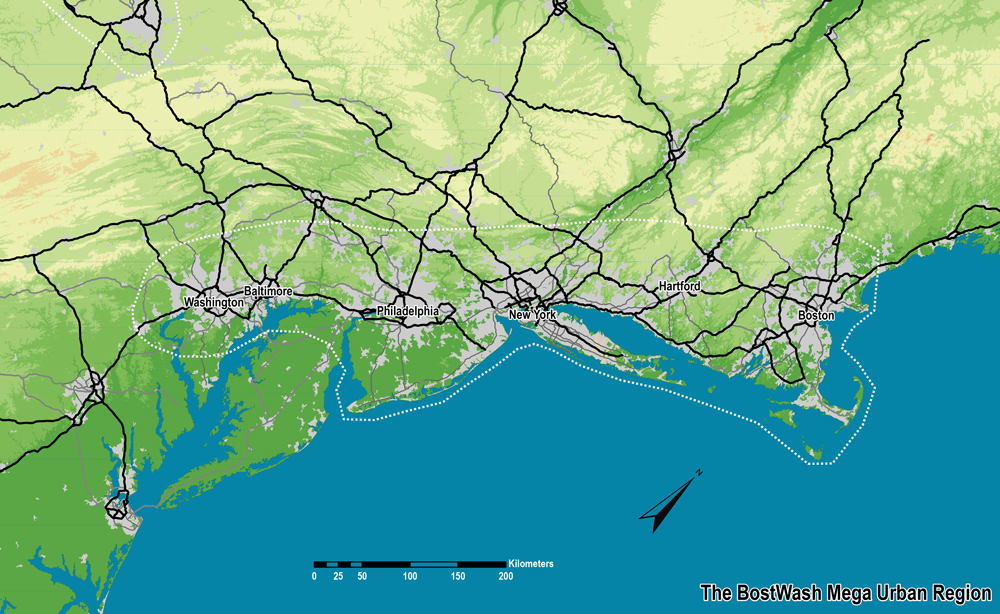

“With a population nearing 44 million, accounting for about 17% of the U.S. population but occupying only 2% of its landmass, the significance of the corridor as a sphere of consumption is indisputable.” So writes Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue about the Boston-Washington (Bost-Wash) corridor in the sixth edition of “The Geography of Transport Systems.” The professor of Maritime Business Administration at Texas A&M University-Galveston should know. Before moving down south, the winner of the Edward L. Ullman Award for outstanding contribution to the field of transport geography lived for 25 years in New York City.

“The New York metropolitan area alone, with a population of 21.2 million, accounts for 7.5% of the national population,” Rodrigue writes in his textbook, before sounding as much like a naturalist as a geographer: “High population densities, over 250 persons per square mile, on a conterminous segment of about 400 miles between Boston and Washington are also observed.”

Where does this jam-packed “sphere of consumption” stand in terms of production and moving goods through the megalopolis? Which factors should companies consider in making location decisions in a mega-urban region whose most operative word may be “paradox”?

Perhaps a longtime traveler to ballparks in the corridor put it best: “Nobody goes there anymore,” said the late New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra. “It’s too crowded.”

“The higher the density, the more it pushes away some activity,” Rodrigue says of the corridor’s relative deindustrialization, even as e-commerce, trucking and rail continue to thrive.The more dense the corridors are, the more they tend to be distribution-focused, he says, noting similar processes that have taken place in much bigger mega-urban regions such as Shanghai and Tianjin in China and Osaka in Japan. “Some love it and some want to get away from it,” including those industrial forces responsible for the corridor’s dynamism to begin with.

Map courtesy of Jean-Paul Rodrigue

While some pockets of reindustrialization have emerged, Rodrigue says he’s ambivalent about the overall potential for reindustrialization along the entire corridor. What activity there is will be linked with new forms of automation, he says, creating a new form of urbanization that’s capital-intensive but not labor-intensive. As for data centers, they are “a very strange beast,” he says, beginning with the fact that their output is weightless. Yet, like the heavy-duty factories of old, they crave strategic proximity to some type of energy source. “They don’t need to be located near a major market,” he observes, “unless latency is an issue.”

Turning our conversation to ports, I asked Rodrigue whether there is promise for more inland port development along the Bost-Wash corridor, or for short sea shipping, whereby containers and cargo travel by marine transport over relatively short distances along a coastline or river. He says on the surface, the corridor would appear ideal for short-sea shipping, but it hasn’t worked out in practice.

“I suspect that the other modes of transportation are too competitive and effective,” he says. Even with congestion, “it’s still more effective to move by rail or truck.” With the exception of roll-on/roll-off ferries in Japan, he observes, most successful short-sea shipping is done between countries, not within one country. “I don’t see short-sea shipping as a strong facet of the corridor’s future, unless the Jones Act is drastically changed,” he says of the federal law requiring vessels shipping between U.S. ports to be built, owned, crewed and flagged in the United States. “If cabotage restrictions were removed, short-sea shipping would naturally embed itself within the existing container network.”

As for container transport on rivers, “we don’t have that much in the U.S. because our rivers are not very long and quickly become waterfalls … the classic fall line,” Rodrigue says. Plus another paradox rears its head: In the United States, commercial flows are east-west and the major river systems are mostly north-south. Inland ports, meanwhile, such as those developed in the Southeast, work well if rail is involved, due again to the competitive nature of rail transport. “We don’t have the double-stack in Europe,” Rodrigue says. “It makes a very big difference.” For the most part, rail-connected inland ports are found in locations just west of the corridor from which the congested markets can be served by truck.

Don’t Rush to Rezone Ports

When it comes to ports, unlike the 60% or more of cargoes arriving at the Port of LA/Long Beach that are destined for other regions of the country, ports along the Bost-Wash corridor such as the Port of New York and New Jersey tend to see cargoes trucked from there to destinations within a couple hundred miles, Rodrigue observes, with longer-range shipping more in the range of 30%.

Dredging and other infrastructure improvements have made the ports in New York/New Jersey and Hampton Roads, Virginia, attractive to shipping lines, Rodrigue says, noting the recent raising of the Bayonne Bridge in New York in order to accommodate Neo-Panamax container ships. Even as the Port of New York and New Jersey itself becomes congested, shipping lines still want to be there, he says, due to the proximity to the “12 lanes of I-95” not far away.

“The port is an anchor point … pun intended … for these corridors,” he says, which means efforts to rezone port-connected land for other uses such as mixed-use may be ill-advised.

“Be very careful about that,” Rodrigue says. “Ports are national strategic assets. We don’t know what capacity we’re going to need in 50 years. There’s a strong temptation to reconvert port land to other uses. There’s nothing more valuable than condo towers on the waterfront from a tax base perspective. However, these infrastructures are very important for national commercial well-being.”

One significant aspect of that importance is e-commerce and cold chain logistics. “On average, what’s in a cold container is twice as valuable,” Rodrigue says, highlighting the cold chain capabilities that have arisen in Baltimore and Philadelphia. “Refrigerated trade is a very interesting cluster of specialization,” he says, “very, very strong.” Which raises another paradox: “In some ways because it’s congested, they want the ship to have a quick turnaround time for distribution. Philly and Baltimore have developed that kind of specialty and it’s actually expanding. It’s quite impressive.”

Just Take the Train?

One more paradox: The Bost-Wash corridor is an ideal market for high-speed rail service such as Acela, building on a history of high-volume commuting by normal-speed rail. In this corridor and other U.S. corridors, however, “passenger rail activity has not emerged effectively,” says Rodrigue. “The rail corridors are there but in connection with long-distance cargo. It’s a paradox — the corridor has become so expensive it forbids the establishment of a high-speed rail system.”

Such service is effective and potentially profitable when it connects major cities, downtown to downtown, he says. But there is never enough money and no business case, in part because the other modes of highway and air work well. In some ways, high-speed rail may be considered an obsolete technology in comparison to new tube and magnetic levitation (maglev) technologies, Rodrigue says, but “you have to build the whole corridor at once, not one piece at a time.”

Pulling back the lens when it comes to site selection, he says since each location decision has its own context and rationale, the complexity of the Bost-Wash corridor means “there is a reason for everybody to be there. Everybody cares about cost, and corridors are attractive for that reason — you can get to a lot of people very quickly,” with e-commerce as close as possible and other firms as far away as possible. The complexity also includes a long list of municipalities, counties and their economic development agencies competing for investment. “It’s not a cohesive entity,” Rodrigue says. “It’s a mess. There are lots of them and they’re all competing.”

Which makes the Bost-Wash corridor, in a sense, a capital example of capitalism at work.