Site Selection in early February hosted a roundtable conference call with a select group of corporate real estate and facilities pros from some of the most powerful biopharma organizations in the world, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Asked where they’re seeing the most progressive policies being implemented in support of life sciences industry growth, one noted, “We’re seeing this within the Americas, specifically Canada, as it relates to housing late-stage clinical staff in country, with significant tax incentives. That has impacted some of our decisions.”

Support from Québec has helped vaccine firm Medicago, which announced, one day after the roundtable discussion, that Investissement Québec had agreed to a three-year extension of the maturity date of its 2003 loan made under the BioLevier program. Medicago VP and CFO Pierre Labbe said the extension of the maturity date of the C$15.3-million loan will allow for a strong balance sheet as the company advances and commercializes its vaccines. In exchange, Investissement Québec gets 1,225,492 common share subscription warrants which may be exercised at a price of $0.50 until December 31, 2018.

Another roundtable participant highlighted the attention his company is giving to the Asia Pacific, especially China, where a change in national healthcare that extends benefits to more of the populace makes for more of a benefit than a risk in the eyes of some biopharma companies.

Another manager cites one Asia-Pacific city-state in particular: “In Singapore, we’ve had very good encouragement with tax incentives and activities.”

Has new legislation influenced location strategy? Participants were nearly universal in observing that the Affordable Care Act in the U.S. is a “grin and bear it” situation, due to the importance of the U.S. marketplace. Also, it remains to be seen whether such developments as the new 2.3-percent medical device excise tax are balanced out by the promise of 30 million new customers and expedited FDA review procedures.

In Puerto Rico, the companies have dealt with the threatened burden of Law 154, and, now, the advent of a newly elected governor. “We have a manufacturing plant in Puerto Rico, continue to manufacture there, and probably will for the foreseeable future,” says one executive of an operation that makes an important over-the-counter product. “This is a plant which, in spite of the changes in the laws, remains a highly profitable operation for us.”

The same company, however, has not invested heavily in Puerto Rican manufacturing, tending toward contract manufacturing agreements that allow flexibility and shifting of work when such developments as Law 154 come around. “We just shifted our operation, and did not have to worry about disposing of the facility,” says the executive.

While data on buildings and properties in such locations is now at a high level, other emerging spots on the globe still lag when it comes to the availability of detailed information about real estate and facilities.

“With respect to Latin America,” said one corporate executive with global responsibilities, “Even though there is more work there, we still have a hard time getting accurate information from resources down there.”

Together and Apart

One pattern evident in project data is change in how corporate functions and divisions are organized. The shift manifests itself in different ways, however, depending on the companies and institutions involved: Some are centralizing, some are decentralizing. Some campuses are becoming more specialized, while others appear to be incorporating more functions in order to instill collaboration as well as control costs.

An executive from one company that’s reeling divisions toward its main campus says, “We feel that by bringing those other parts of the company onto campus, we gain a knowledge base and a mass of talent that we’ve been missing out on because we’ve been separated geographically. And economically, since we still have quite a bit of space to build on, it’s still cheaper to build on land we’re paying for than go out and purchase additional office space. So we are beginning to cluster the different parts of the organization within major campuses.”

Another multinational is going the opposite direction, and streaming different functions out from its main sites. Roundtable participants agreed that company culture plays as big a role as cost specifics and square footage in determining which approach is best. They also sounded a note of caution about multifunctional facilities.

“From an asset disposition perspective, large multifunctional sites can be very challenging,” says one executive. “We’re being very strategic in how we set them up. Office, sales and marketing are flexible and dynamic. Manufacturing and R&D sites are siloed.”

“I agree with the exit strategy issues because they’re big,” says another whose portfolio includes space in the Bay Area designed with academic interaction, idea exchange and serendipity in mind, “but they’re going to make more money off the drugs than off the exit strategy.”

Nevertheless, “offices are straightforward, but manufacturing or research [space] is where we end up banging our heads against the wall” when it comes to asset disposition, said another roundtable participant. Environmental issues unique to life sciences — animal health sites, for example — add to a unique list of site challenges when shutting down a location, including decommissioning and decontamination. “A lot of times,” says one experienced executive, “you’re not going to find a like-kind user. And it gets expensive when you have to take the place apart, or even demolish. Depending on what the use was, you may have to scrap it, or clean it to an acceptable standard where it can be reused.”

Some of those headaches are being removed by the increasingly superior workspace and campuses purveyed by such REITS as Biomed Realty and Alexandria.

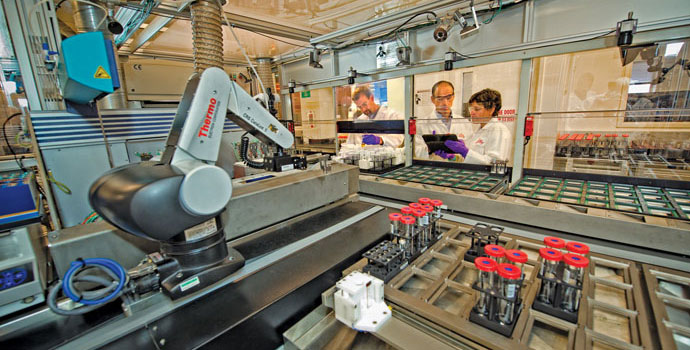

With the slogan “Global Innovation for Value Creation,” Chorus, an autonomous unit of Eli Lilly and Co. aimed at cost-effective drug discovery and development, operates on a virtual model that includes some 200 provider partners covering much of the globe, including Lilly’s own labs (pictured).

“We’re just finishing up a lease on space in California with BioMed,” says one executive. “It’s an attractive way to get in when you don’t want to go through the expense of building a facility, and an attractive way to get in fairly small. We’ll see more of that as we continue to partner with small startups. It gives us flexibility. We can just take space in the existing building, sign a fairly short-term lease, and if the product takes off, great, we can move it to an owned facility. Those organizations will come to have a prominent place in our business.”

Indeed, partnering with institutes and with academic institutions continues to be a prime avenue to the leading life sciences location factor: talent. Cambridge, Mass. (with Harvard, MIT and Mass General nearby), and San Diego, Calif. (with the Salk Institute, Scripps and UCSD, among others), are stars in this universe. Partnering more productively is something all companies seem to want to do more of.

“We’re working right now with a university on a new product,” says a roundtable participant. “We don’t have the corner on the market when it comes to R&D. If we can partner with universities, it just makes us stronger.”

“With my previous employer, that’s why we went to the innovation hubs,” says another. “With the advancements in biology, they wanted to be in those hotbeds. For the company I’m with now, some of their development is in Europe in a university setting. You follow the talent.”

R&D (R)evolution

Since so much of that talent is entrepreneurial in nature, several collaborative workspace models have made their debut recently. They have new approaches to intellectual property, new arrangements with regard to real estate and often new names, but are backed by some of the most well known names in the industry. And in some cases these centers can help solve some of those asset disposition headaches.

“As part of the disposition of our Montreal facility, we formed a public-private partnership with the Quebec government and a couple of local startups,” says one of the roundtable participants.

Another example is blooming on formerly under-utilized Johnson & Johnson property in San Diego, where the company’s Janssen Labs operation (which includes J&J’s own R&D center) just celebrated its first anniversary in January. The idea is no-strings-attached workspace and equipment provision for entrepreneurial biopharma firms. Janssen Labs offers singular bench tops, modular wet lab units and office space on a short-term basis, allowing companies to pay only for the space they need, with an option to quickly expand when they have the resources to do so. Companies residing at Janssen Labs also have access to core research labs hosting specialized capital equipment and shared administrative areas.

Diego Miralles, M.D., is head of Janssen West Coast Research Center, a Janssen Labs operation on formerly underutilized Johnson & Johnson property.

Diego Miralles, M.D., is head of Janssen West Coast Research Center. He says the biggest hurdle at the outset was convincing people Janssen really meant what it said.

“People said, ‘No, tell the truth. What’s the catch?’ he says. “The open approach is really one of the biggest elements of its success. Entrepreneurs like to be free, and if you constrain those choices, they are not interested. They have other options.”

Through the “no strings attached” model, Janssen R&D does not take an equity stake in the companies occupying Janssen Labs, and the companies are free to develop products either on their own, or by initiating a separate external partnership with Janssen or with any other company.

Miralles says the goal is to make the site “the best place to start a biotech company in the world. I would say by the testimonials we have, we are going that direction.”

Eighteen companies have been accepted into the space since it launched, from a pool of applicants that numbers more than 200. While several hail from the San Diego life sciences hotbed, they also come from Louisiana, Michigan and North Carolina, as well as Mexico and Italy. One firm already has graduated to a larger building in the region, after doubling in size and then outgrowing Janssen’s capacity, “but they never could have done it without our hub,” says Miralles, who expects the number of tenants to grow to 20 or 22 by this spring.

Providing a professional level of management was critical, unlike at some incubators where the basic message is “Good luck, here’s your bench, and call the fire department if you have problems,” says Miralles. Prescience International, which also manages an operation in San Jose, Calif., provides that level of professionalism, which includes thorough training of the tenants in everything from hazmat to legal to equipment maintenance. The deal with Janssen even includes corporate communications.

“It’s all provided for in your lease,” says Miralles. “It’s a comprehensive package. The idea is to have companies focus on value creation.”

To mark its first anniversary, Janssen Labs has added two offerings: The Concept Lab is a shared laboratory that offers entrepreneurs affordable access to single bench spaces to perform early-stage research before committing additional capital. The Open Collaboration Space is an open-plan office setting that provides companies and individuals with desk space in an environment that facilitates interactions with other life-science entrepreneurs. With these additions, Janssen Labs can now accommodate more than double the number of companies as when it opened.

Janssen lab space and space occupied by the tenants is carefully separated by magnetic doors. Asked how the site pays for itself, Miralles explains, “We own the site, and we make it really nice. We focus on providing optimal services. It’s not a real estate play for us. For us, the interest is to have the biotech industry succeed, and to generate transformational products to which we eventually have access. From the economic development or real estate play perspective, you want it full and you want revenue. Our goal is to have it meaningfully full, with projects from good companies.”

Miralles says the four elements of biotech are money, science, people and space. “The market has to take care of the money, science and people,” he says. “We are focused on the space.”

Asked if he’s looking for other places to take the Janssen concept, he says, “Indeed. We want to build on our brand.” The scope of his research is global, and it’s open to partnerships with other organizations. “I’m looking at places where innovation is very active,” he says. “You want the place to be thriving, full of energy, creating a real ecosystem.”

Nice Neighborhoods

Janssen isn’t the only new kid on the block. Pfizer has launched its own “open innovation” program, the Centers for Therapeutic Innovation (CTI). CTI has established partnerships with 20 leading academic medical centers (AMCs) across the United States, and supports collaborative projects from four dedicated labs in Boston (where CTI is headquartered), New York City, San Francisco (where Pfizer works closely with UCSF), and San Diego. CTI received well over 300 proposals from its first round of applications, and to date has selected approximately 20 programs to initiate. CTI laboratory staff include Pfizer employees working side-by-side with leading basic and translational science investigators and post-docs from the AMCs. “This model offers leading investigators the resources to pursue scientific and clinical breakthroughs by providing access to select Pfizer compound libraries, proprietary screening methods, and antibody development technologies that are directly relevant to the investigators’ work,” says Pfizer.

With the slogan “Global Innovation for Value Creation,” Chorus, an autonomous unit of Eli Lilly and Co., is a global, early‐phase drug development network that focuses on designing and executing lean and highly focused development plans that cost-effectively progress potential medicines from candidate selection to clinical proof-of-concept (poc). Looking for its labs? They could be anywhere, as Chorus operates on a virtual model with some 200 provider partners covering much of the globe, including Lilly’s own labs. The program’s most recently announced partnership was in October 2012 in Montreal, Que., with TVM Capital Life Science, a transatlantic venture capital firm.

“We are very impressed by the speed and commitment with which Lilly did set up a Chorus team in Montreal and we have already received a lot of very positive feedback from the Quebec life science business community for the work that Chorus is doing with TVM,” said Dr. Hubert Birner, managing partner of TVM Capital Life Science.

Finally, a new lab concept is also emerging from the healthcare side of the life sciences equation: United Health Group’s Optum subsidiary, which offers a suite of healthcare services and information products, in January joined with Mayo Clinic to launch OptumLabs, which they describe as “an open, collaborative research and development facility with a singular goal: improving patient care.”

It sounds a lot like what the biopharma world is trying to do at the same time. And it comes at a time when measures such as the Affordable Care Act are driving the healthcare and biopharma worlds toward convergence.

The launch location for OptumLabs? Cambridge, Mass. — the beating heart of a Greater Boston area that was again recognized this year by Jones Lang LaSalle’s annual “Global Life Sciences Cluster Report” as the No. 1 cluster in the nation.