An incubator of aerospace and aviation engineering going back nearly a century, the Lockheed Martin plant at Little River, Maryland, has a storied history. It was there that the Glenn L. Martin Company’s developed the B-26, a medium-range bomber that flew more than 100,000 sorties during World War II. Parts of Gemini and Apollo spacecraft came out of the plant decades later. Shuttered last year as part of a corporate re-organization, the cavernous facility — in fairly short order — has received a new lease on life.

Literally. Rocket Lab, an agile player in the evolving commercial space game, agreed in November to rent and refurbish 113,000 sq. ft. from Lockheed Martin for a Space Structures Complex. To assist with project costs, the Maryland Department of Commerce is providing a $1.56 million repayable loan through its Advantage Maryland program. Slotted to create 65 new jobs, it’s a project the state government seemed eager to get.

“With our state’s close proximity to several federal and defense agencies, combined with Maryland’s abundance of talented tech and engineering workers,” said Commerce Secretary Kevin Anderson in a statement, “this facility is sure to bring much success to both Rocket Lab and Maryland’s innovative space industry.”

Founded in New Zealand in 2003 and headquartered now in Long Beach, California, Rocket Lab is what founder and CEO Peter Beck calls “a one-stop space shop.” It provides satellite design and manufacturing for both the U.S. government and private clients and launch services to customers that include NASA, the U.S. Space Force and the National Reconnaissance Office. Rocket Lab technology went into the James Webb Telescope, developed in part at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, just northwest of Washington, D.C.

“Most aerospace companies, you’re either a satellite guy or you’re a rocket guy,” Beck tells Site Selection. “We’re both,” he says. “So, when a customer comes to us, we can build a satellite, then we can launch the satellite and we can even operate the satellite with them.”

Among recent, high-profile projects, a Rocket Lab Electron rocket sent NASA’s CAPSTONE CubeSat on a path toward the moon from the company’s Launch Pad 1 in New Zealand. CAPSTONE has settled into a pioneering lunar orbit, the same orbit planned for Gateway, a small space station from which NASA plans to return humans to the Moon.

“We operated the spacecraft,” says Beck, “until it was time to turn it over to NASA.”

Rocket Lab’s Middle River facility is to focus on composites and composite structures — “We’re the only company,” says Beck, “that’s building fully carbon composite launch vehicles” — with an eye toward building ever larger rockets.

“For us to be able to pick up a facility of this size, one with large, open spaces and a hugely thick foundation, is incredibly rare,” Beck says of the Lockheed Martin complex.

The facility offers other advantages, as well. Barge access will allow Rocket Lab to float spacecraft and rockets down Chesapeake Bay to its installation at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility at Wallops Island, Virginia. Wallops, says Beck, will be the exclusive launch platform for the company’s Neutron rocket, now in development.

“Having manufacturing capability so near the launch site is super, super helpful,” he says.

The Space Structures Complex will expand Rocket Lab’s existing footprint in Maryland, where the company already operates a manufacturing facility for satellite separation systems and CubeSat dispensers in Silver Spring. Its experience in Maryland, Beck believes, bodes well for Rocket Lab’s expansion there.

“There’s a deep aerospace community with lots of experience. There’s also a really deep composites industry. You can have a great building, but you’re going to need to fill it with the best people to be successful, and what we’ve seen is a culture of getting stuff done that really aligns with our company’s core values.

“We’re super lucky,” Beck believes, “because not just in Maryland but down the road at Wallops Island we’ve always been greeted with warmth and, quite frankly, excitement. They’ve really rolled out the red carpet, and it’s been a great experience for us.”

Genesis: Beyond the Logo

Like Rocket Labs, Genesis Engineering has its fingers in numerous pies, opportunities being what they are in the new Wild West of space travel. Unlike Rocket Labs, Genesis is Maryland-born and bred. And Genesis, let it be known, engineered a singular coup in the history of product placement.

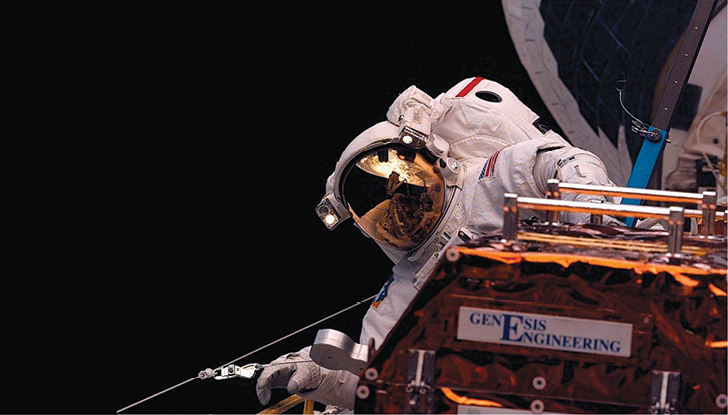

The Genesis logo, attached to Space Shuttle Discovery

Photo courtesy of Genesis Engineering

As astronaut Mike Massimino dangled outside Space Shuttle Discovery during a 2009 spacewalk, a NASA camera swung around to capture what looked like a bumper sticker. Blue letters on a white background, it read “Genesis Engineering.” Today, that memento hangs on a wall at a Genesis conference room at the company’s headquarters in Lanham, near NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“That was the last time they allowed a contractor to fly their logo,” says Robert Rashford, Genesis founder and CEO. “We got free advertising for two days in space. Then they said, ‘No more of that.’”

Rashford himself is an interesting story. The native of Kingson, Jamaica, emigrated to the U.S. in 1978, earning a degree in mechanical engineering from Temple University. After landing his first aerospace job with the space division of RCA in New Jersey, he moved to Maryland for a position with Fairchild Space and Defense, where he says he learned to build tools employed by spacewalking astronauts. Banking that experience, Rashford struck out on his own. He founded Genesis in 1993, seeding the new company’s bank account with $350.

Today, Genesis employs about 200 people spread across four buildings in Lanham. The work that earned it that bumper sticker included supplying NASA with tools and tool lockers for stowing all manner of space gear packed to exacting specifications.

“We also wrote scripts for the astronauts on the cadence of the spacewalk. That was our bread and butter for several years. Then, we designed and built hardware for the James Webb Telescope.”

“Having manufacturing capability so near the launch site is super, super helpful.”

— Peter Beck, Founder & CEO, Rocket Labs

The granular knowledge Genesis gathered from supporting shuttle spacewalks inspired one of the company’s most ambitious projects to date. Who knew that spacesuits designed for EVAs (Extravehicular Activities), are essentially one-size-fits all? Ill-fitting suits, says Rashford, can cause skin abrasions and joint problems. Heating and cooling systems can leak water, cutting spacewalks short. The Genesis Single Person Spacecraft, (SPS) designed with the International Space Station, NASA’s Gateway program and space tourism in mind, is a self-propelled module that a spacewalker would board to operate outside the mothership — sans spacesuit — and without the lengthy hours of pre-breathing required to prevent getting the outer space version of the bends.

“You can eliminate all of that,” says Rashford, “because the pressure inside the vehicle is the same as inside the spacecraft.”

Orbital Reef, conceived as a space-based business park, is a potential partner for SPS, although Rashford suggests that project — led by Blue Origin — is being slow-walked due to other Blue Origin priorities. Genesis, says Rashford, is looking for an investor to see SPS to the finish line.

In the meantime, Genesis is developing its first CubeSat, a miniaturized satellite for space research, creating a propulsion system for a private customer and bidding on a billion-dollar contract with Goddard to produce mass spectrometers for space applications.

“We feel the time is right to do it,” Rashford says. “We have the staff, the confidence, the know-how and the partnerships. We think we stand a good chance of winning that contract because of what we have to offer.”