Atlanta-based DC BLOX is aiming for a very specific target: the infrastructure needs of businesses and communities in emerging and underserved markets throughout the southeastern U.S., where robust connectivity and Tier 3 data center availability is limited. With multi-tenant data centers in Atlanta, Chattanooga, Huntsville and now Birmingham, it’s only getting started.

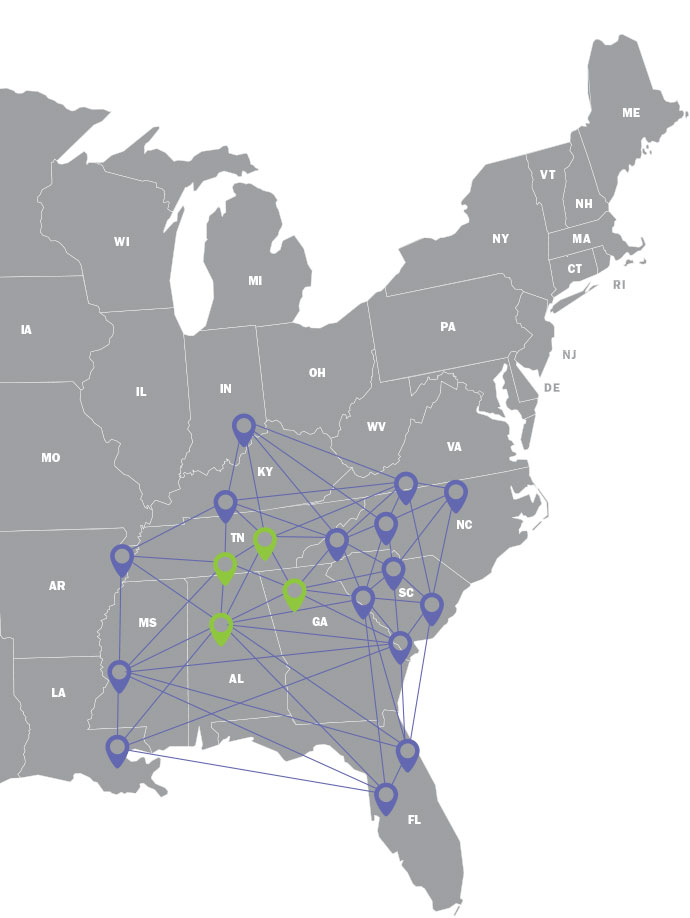

The company’s market map shows 15 more cities — from Louisville to Tampa, and from Raleigh to New Orleans — where it plans to site future data centers. One of the parameters is to not only locate in underserved cities, but to, when feasible, site the facilities in underserved parts of those cities. The company’s site in Chattanooga’s Southside is in a neighborhood once known for abandoned warehouses and industrial buildings, but now experiencing a revitalization.

CURRENT LOCATIONS

- Atlanta, GA

- Birmingham, AL

- Chattanooga, TN

- Huntsville, AL

FUTURE LOCATIONS

- Augusta, GA

- Charleston, SC

- Columbia, SC

- Greensboro/ Winston-Salem, NC

- Greenville/ Spartanburg, SC

- Jackson, MS

- Louisville, KY

- Memphis, TN

- Nashville, TN

- New Orleans, LA

- Orlando, FL

- Raleigh, NC

- Savannah, GA

“Chattanooga is turning out to be a really good location,” says Kurt Stoever, chief product and marketing officer for the company, noting the startup and innovation vibe in the area. “We’ve already invested in additional power and space.”

The Birmingham facility, which opened in July, is in Titusville — the home neighborhood to Condoleeza Rice and other notable residents, but an area also notable for its more recent neglect. “This data center will help strengthen Birmingham’s future economy in a more digital world, as well as utilize a long-vacant property to revitalize the surrounding area in one of our neighborhoods,” said Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin of the project, located on the 27-acre former Trinity Steel manufacturing site. Funds from the city’s sale of the property are being invested in street maintenance and home repairs, among other things.

Victor Brown, vice president of business development at Birmingham Business Alliance (BBA), says when DC BLOX landed in Titusville, it didn’t just create jobs. “When communities don’t have infrastructure that might lend itself to big recruitment projects, that doesn’t take them out of the economic development game,” he says, noting the potential for suppliers and others who may seek to be in proximity to the flagship facility.

The company also pledged funds and space for the youth of the area. When Stoever told the county representative for Titusville that the company would be happy to adopt the park across the street, he was told instead that what the community really needed was a place for kids to do homework.

“We donated equipment and furniture and lined up partners to support equipment and connectivity to allow kids to go to the community centers and do their homework in the neighborhood, because not all the kids had access at home,” Stoever says. “Part of what we want to do is serve the community, but the second part is we want to connect globally — use the data center to connect to places you might not have connected to before.”

“The State of Alabama and the City of Birmingham care deeply about the prosperity of their citizens, and are working to bring in companies like ours to invest in their communities and bring jobs to the region,” said Jeff Uphues, CEO of DC BLOX. “They understand that a data center is core infrastructure that attracts other technology-dependent companies, and we couldn’t be more excited to be a part of it.”

Estimated economic impact of the project during the construction and operational phase is $94 million on the Birmingham metropolitan area.

“Because data centers represent the backbone of the technology infrastructure, we see strategic benefits for Alabama to host state-of-the-art centers that keep the world connected,” said Alabama Commerce Secretary Greg Canfield when the land was purchased in July 2018. “DC BLOX is joining an impressive roster of technology companies selecting Alabama for their data centers, and we want to see that list grow.”

In addition to the state, the city and the BBA, DC BLOX worked closely with the Jefferson County Commission, Jefferson County Economic and Industrial Development Authority, Titusville Neighborhood Association, Birmingham Industrial Development Board, Alabama Power Co., Spire and the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama.

Constructing a Strategy

Before Stoever came on board, site searches had focused more on brownfield buildings on small edge sites, connected via the company’s own dark fiber. Now the team is focused on greenfield sites and purchasing lit network services. “It’s easier to buy suitable dirt,” he says. “We light the fiber ourselves, but we buy the service so we don’t have the expense of building our own network. Trenching and rights of way take so much time.”

To develop a site selection strategy, the DC BLOX team contracted with Connected2Fiber to do analytics. “We created a model that basically takes a whole host of criteria and attributes, gathers all the data from Dun and Bradstreet, Aberdeen and other sources, and the model comes up with a score that says, ‘You all ought to think about this location.’ Attributes include demand, economy, network infrastructure, incentives — about 35 criteria.”

The model has been adjusted, he says, to include IP traffic flow, cloud traffic flow, and what levels of traffic are flowing into and out of the metro area in different cloud modes. Absorption — how much power is available to be taken down in a given market on an annual basis — is important too. The model also looks at job and GDP growth, the number of managed service providers (MSPs) in the market and factors such as median household income, in order to characterize the wealth creation of the MSA.

“Out pops a number, and almost every single time it says, ‘You ought to go to Atlanta,’ ” Stoever says of the company’s home base, where the economy has been humming. “But part of our criteria is being underserved, which for us means a lower basis of competition. Then it says, ‘Charlotte,’ and we say nope, not doing that either. So we filter and we get a smaller list, based on what we think the absorption will be.

“The last run I did included everything from Colorado to the East Coast,” he says. “We filter it down based on competitors, then available power in the market, and the final thing we filter on is our ability to reach the meshed network design in an economically feasible fashion.”

For example, the list may say to go from Chattanooga to Columbus, Ohio, Stoever says. But that means the data center has to carry the financial burden of paying for a redundant path there that can sustain the necessary performance level of sub-five milliseconds. “It can be done, but it’s going to cost a lot of money,” he explains. “So we look at closer MSAs — Knoxville, Memphis, Lexington, Louisville, Evansville.”

Further filtering occurs if field work reveals that seemingly attractive markets are full of hospitality and durable goods — sectors without a propensity to outsource their data center needs to a colocation site. Once all the filtering is done, the conversations begin — with power companies, real estate experts, economic developers, elected officials and “the local attorney who seems to know what’s happening in the city,” Stoever says. The company then seeks incentives in exchange for the value it proposes to bring via investing millions into a node that promises to improve the area’s digital economy. If it feels good, as it did in Birmingham, Stoever says, “We’ll get more specific on the dirt we want to procure,” based on further criteria such as sufficient setback, security, lack of seismic or traffic disturbance, skirting the floodplain, and being as close as possible to a substation.

“I spend the most money on power,” he says of data center costs. “So if power comes in at 15 cents per kilowatt-hour, I’ll probably find another place.”

Making a Difference

Stoever says the Southeast is not only more affordable than the population centers on the coasts, it’s also a region more people are moving. “We also find they’re more amenable because the data center industry has really focused on the big NFL cities.”

Notwithstanding the recent streak of data centers landing in the Southwest, Stoever says, “Water will be an issue for the data center operators when people start saying there’s not enough water for the public good because data centers are taking it away. I foresee the desert data center markets being challenged. Maybe it’s 20 years away, but unless it starts snowing or raining more, Lake Mead is not going up.”

More DC BLOX centers will be going up, however, as the company hunts for places where corporate end users have a lot of their own data centers, but are ready to offload. “The edge is unfolding,” is the way Stoever describes the phenomenon.

“We have six markets we’re highly interested in, and another 12 to 14 that are possibilities,” he says. “Depending on how we want to apply our capital, we could have three to four in flight at the same time, in some phase of parallel deployment. Once we complete the four, the other two require more field work. And then it’s a step back, where we’ll open up the analysis again and look to where we go from there. The beauty of our design is we always buy enough property so if the site is rent stabilized, we can build more in and continue to grow.”

As they do, he says, the nuance of location will continue to be important. So will pledging 25% of construction contracts to minority- or women-owned firms (the project has reached 30% in Birmingham). The easy choice in Birmingham would have been to go over the mountain into the suburb of Homewood, “buy some dirt there, and say, ‘Fine. I don’t have to worry about crime, I can get incentives, I can get power.’ We made a decision to be closer to the city, the community, and to things like Innovation Depot. It matters to us.

"We decide wherever feasible not to take the easy way out, and go where we’re going to make more of a difference," Stoever says. "We want to be closer to where our investment has an effect on the people nearby.”