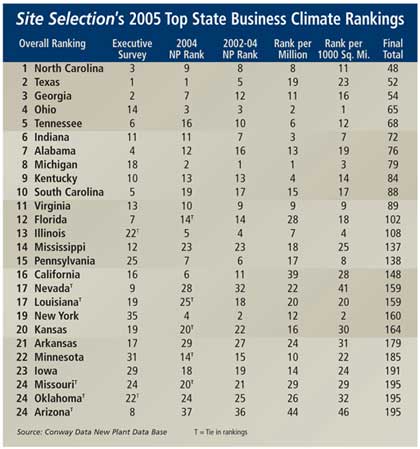

aving forfeited its three-year claim to the Top Business Climate ranking in 2004, North Carolina is back on top. And Texas, which unseated the Tar Heel State in last year’s contest, finished a more than respectable second. Texans should find some consolation in placing first in the survey of corporate site seekers, which counts for 50 percent of the overall ranking. The other 50 percent of the ranking is based on states’ performance in four categories associated with Site Selection’s proprietary New Plant database (see the Top State Rankings chart). The ranking, therefore, is a blend of objective, actual new or expansion project announcements and subjective input from corporate site seekers who indicated their top states in an online survey conducted in August.

Whether North Carolina is embarking on a new multi-year winning streak remains to be seen. In any case, the state is managing to grab the attention of corporate real estate executives and investors alike — without benefit of the Lone

|

Star State’s two-year-old Texas Enterprise Fund, which was reauthorized in its latest legislative session to the tune of US$180 million for the next two years. A companion Emerging Technology Fund got $200 million to help lure high-tech operations to the state.

The workhorse incentives in North Carolina’s stable are the One North Carolina Fund, which has helped lure more than 17,000 jobs and more than $2 billion in investment to the state since 2001, and the Job Development Investment Grant (JDIG), which awards up to 25 grants annually to strategically important new and expanding businesses and industrial projects. Since 2003, JDIG grants have helped attract $1.9 billion and create more than 10,000 jobs.

Recent projects in which these incentives played a role include a $92-million expansion of GlaxoSmithKline’s manufacturing facility in Zebulon, N.C.; a $4.2-million investment from turnstile manufacturer Boon Edam Tomsed, Inc., in Harnett County; and an $8-million factory in Surry County for Poli-Twine, Inc., a Canadian rope and twine manufacturer.

But incentives played a marginal role in North Carolina’s biggest investment of 2005, which was Dole Food Company owner David Murdock’s announcement in September that he plans to transform a former textile mill in Kannapolis into the North Carolina Research Campus (see page 694). “I’ve worked in most of the states, and I build all over the country, but I’ve never found any state as cooperative as the state of North Carolina,” he tells Site Selection Senior Editor John McCurry.

For his part, Governor Michael Easley says his strategy for making North Carolina cooperative and competitive is not complicated.

“Our interest has been the simple strategy of improving education and reducing the cost of doing business,” he

|

explains. “Incentives matter, especially when you’re trying to lower costs, but right now, with the federal trade policies forcing low-skill jobs overseas, we can’t compete with low costs. So we have to compete on high skills.” That strategy lies behind significant investment in all levels of education in the state in recent years. “Business tells us the skills they need, and we provide those skills,” Easley adds.

At the same time, adds the governor, “We’re starting to lower the tax burden on business, and we’re watching closely our workers’ comp program. What we’re finding is an intersection in this state of a more skilled work force than you’ll see around the rest of the country and lower business costs.”

Take the biotech industry, he argues, which is clustered in several areas around the United States, such as metro Boston, San Diego, Maryland/Virginia and North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park. “We can do everything they can do about 25 percent cheaper in terms of labor capital expenditures and land acquisition.

“The skills are rising much faster than the cost of doing business is,” says Easley, “and that makes our state attractive to business.”