PLEASE VISIT OUR SPONSOR ? CLICK ABOVE

|

|

Can Kvaerner Re-Launch U.S. Shipbuilding?

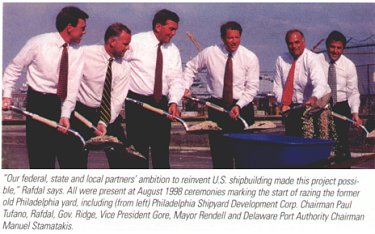

“In the small western Norway town where I was born and raised, Union Carbide set up a big operation in the 1920s,” Rafdal continues. “So growing up in the 1960s, I always heard that all high technology came from America. Now, my company is coming to America to teach the U.S. how to build ships that add value with technology.” Is it ever. Kvaerner’s advanced new facility is the first U.S. shipyard built since World War II. And it’s rising at the storied, 196-year-old Philadelphia yard the U.S. Navy closed in 1995 after employing 4,000 in the early 1990s. Everything about the deal is huge: a 114-acre (57-hectare) site; US$430 million in federal, state and local incentives; a 545-page agreement and a likely minimum of 1,000 jobs. Equally high are the yard’s political and economic stakes. The project will likely be a key plank in Vice President Al Gore’s U.S. presidential run. After all, the future of U.S. shipbuilding is riding on Kvaerner’s fortunes, many analysts insist. Accordingly, reopening the old yard transcended partisanship. Republican Gov. Tom Ridge and Democratic Philadelphia mayor Ed Rendell were both heavy lifters in landing Kvaerner on a site along the Delaware River, which rhythmically smacks against the hulls of mothballed ships. “With this state-of-the-art facility, we hope to generate the rebirth of U.S. commercial shipbuilding,” Ridge says.

In for the Long Haul “Yes, it is a lot of pressure,” he says, smiling slightly. “But for several years we had been looking at several locations to enter the U.S. market. What made this project possible was our federal, state and local partners’ ambition to reinvent U.S. shipbuilding. “We are proud to be selected. We believe Kvaerner’s expertise will ring Philadelphia’s revolution bell for jobs, technology and innovation.” It won’t be easy, though. Sitting where Ben Franklin flew kites in electrical storms, Kvaerner’s yard is a figurative lightning rod. Almost by definition, it’s immersed in a whirlpool of controversy; and that eddy won’t soon subside, for shipbuilding is a very long-term business. That’s sharply reflected in the 20-year projected payoff for Kvaerner’s hefty incentives, which have drawn persistent knocks from some quarters. Still to be solved are a host of complex, politically charged supplier issues. And Kvaerner’s Philadelphia risk exposure has ratcheted up with the global economic goblins that Asia’s currency crisis uncorked. The amiable Rafdal, though, remains unfazed. “With some Asian currencies dropping 70 percent, this is a tougher job,” he allows. “Shipping has a lot to do with currency, and it’s cheaper now to build large ships in Asia. But no-tech, low-tech ships moved to Asia some 30 years ago [because of] hourly wages and currencies. “So it is very important to build more sophisticated ships, as we will in Philadelphia. That process takes time, but I am not concerned about investing in America. You must watch shipbuilding in spans of 30 years, not two to three years, and we have a long-term commitment to stay.”

Moreover, Kvaerner has successfully redeveloped shipyards in Finland, Germany, Norway and Scotland, part of the bold plan it launched in 1996 to become the first global shipbuilder. (That plan included relocating Kvaerner’s headquarters from Oslo, Norway, to London, where it had acquired Trafalgar House for $1.4 billion.) Philadelphia’s yard will be a clone of Kvaerner’s flourishing yard in Rostock in the former East Germany, “one of the world’s most expensive nations,” Rafdal notes. Aided by sizable incentives, Kvaerner spent $400 million in turning the Warnow Werft Shipyard into one of Europe’s top container ship builders.

A 99-Year Lease Though closed, Philadelphia’s old yard was still a powerful location draw for Kvaerner, which signed a 99-year lease on the prime nautical real estate. Now jointly owned by the state, city and Delaware River Port Authority, the site boasts two 1,092-ft. (331-m.) dry docks, the largest available on the U.S. East Coast and among the world’s biggest. Building them today would be virtually impossible. Pennsylvania’s award-winning Land Recycling Program also resolved all site environmental issues, including potential liability. As promised in the incentives agreement, Kvaerner set up another major local operation in June 1998, relocating its U.S. headquarters from New England to a downtown Philadelphia skyscraper. “Many Americans don’t know who we are, though 7,000 of Kvaerner’s 60,000 employees work in the U.S.,” Rafdal says. “We hope the new headquarters makes our U.S. presence more visible.”

The Incentives Squall Predictably, those incentives rankled some. One of the largest U.S. public-sector subsidies, Kvaerner’s incentives inevitably raise The Big Question: Will the payoff be worth it? Like a bend in a river, the answer will only be shaped by time. That, though, hasn’t stopped critics, who charge that Kvaerner’s incentives average $400,000 per direct job. Kvaerner’s $80 million in federal subsidies have drawn heavy fire from the American Shipbuilding Assn. (ASA). Kvaerner’s public financing, ASA officials charge, will distort the U.S. industry, damaging U.S. firms that build Navy ships and potentially draining national security. The ASA, however, opposes a global pact to abolish national subsidies (see “Kvaerner’s Tale of Two Treaties”).

Yards ‘Must Have Support’ To get that support, Kvaerner made a modest $50 million upfront investment. Long term, though, Kvaerner committed $250 million, including $120 million for yard capital improvements (starting after the project’s fifth year) and $80 million to buy its first three U.S.-built ships. “Reselling those ships does not stress us,” Rafdal says. “With few U.S. container ship and tanker players, there is a need. And we know you can not train on steel structures. For long-run success, you must begin doing the real thing, as with those three ships.” Joined by private-sector leaders like Bill Avery, CEO of Philadelphia-based Crown, Cork & Seal, state, local and federal officials courted Kvaerner for two years in Norway, Germany and Philadelphia. They were not alone. Almost every area with a shipyard to develop was wooing Kvaerner. Those leaders were eager to avert a repeat of 1995’s aborted courtship of German shipbuilder Meyer Werft, whose proposed privatization would’ve created 3,000 yard jobs. But when a state counteroffer cut incentives, Meyer Werft cut Philadelphia from its location short list.

The Supplier Gold Mine Debate has already surfaced over Kvaerner’s purchases from foreign suppliers, including a $28 million, Portuguese-made gantry crane that can lift 600 tons (560 metric tons). Those foreign buys irked state Senate Democratic whip Leonard Bodack, who’s from the steel-producing area including Pittsburgh. “Kvaerner . . . is looking . . . like a raw deal . . . shipping [Pennsylvanians’] hard-earned tax dollars overseas to boost other economies,” Bodack said in a letter requesting a state auditor investigation. Counters Rafdal, “We are putting our best efforts and a lot of time into trying to find U.S. suppliers and equipment.” “Most of it comes from Europe,” Rafdal says. “All commercial shipbuilders, even Americans, buy some European equipment. On the first ship built here, we know we may have to buy equipment from Europe that’s not supplied in the U.S. To be globally competitive, you must purchase globally. And, yes, we have always been very clear about that and documented thoroughly, as we anticipated a discussion like this.” What critics are missing, Rafdal insists, is the difference between yard construction and yard operation: “The construction and equipment investment is essentially a one-time situation. Ultimately, I’m quite sure we will utilize many regional suppliers. Our long-term survival depends on it.”

Schooling U.S. Suppliers Joined by state officials, who’re monitoring supplier choices, Rafdal is holding 10 “outreach sessions.” The first session in late September drew 600 suppliers (necessitating two separate sessions), most from Pennsylvania. The meetings, says Rafdal, “educate in the areas Kvaerner suppliers must excel: price, technology, experience and fast-track delivery.” But that learning will take time, Rafdal cautions: “Commercial supplying is very different from the Naval work most U.S. suppliers have done for two decades.” Kvaerner plans to use far fewer direct suppliers than the Navy, with “80 percent of work handled by perhaps 35-50 suppliers,” he says. “That is more effective. But to serve us, they may need to reorganize their ways of working or create joint ventures.”

Labor Flexibility Essential Indeed, Kvaerner’s trademark work-force flexibility is a make-or-break factor. Labor opposition to its system fueled the 1997 shutdown of Kvaerner’s Gibraltar repair facility, a rare turnaround bust. Before making its U.S. commitment, Kvaerner carefully forged a broad labor pact. Both sides won battles in the agreement signed in September: It retains the AFL-CIO’s Metal Trades Dept. (MTD) in representing a dozen yard trades. The MTD though, approved Kvaerner’s multi-skill job definitions. Already, those jobs have generated 4,500-plus applicants, many former Philadelphia yard workers. Says MTD President John Meese, who negotiated with Rafdal, “Kvaerner is a responsible employer relying on worker motivation and expertise.” Labor’s choices, he adds, were “to change to compete or to be out of business.” Rafdal concurs: “The global economy has made unions and management closer. After pressing us and pressing us, European unions became more cooperative. If you’re fair and honest, labor will understand. If you do not settle such issues, other shipbuilders will beat you.”

A Ripe U.S. Market As Kvaerner Senior Vice President Trond Andresen observed while scouting U.S. sites in late 1997, “ | is obviously an interesting area [because] U.S. shipbuilding . . . hasn’t been investing in modern yards for today’s demands and technology.”

Still a Slippery Slope “If that yard builds two to five ships a year,” McCullough says, “as an ex-banker, I can say it will recreate a U.S. industry that died.” Kvaerner plans to build four ships a year, but some industry analysts are skeptical about its prospects in the heavily protected U.S. market. Most agree, though, that if Kvaerner can’t do it, competitively building U.S. ships may be impossible. Meanwhile, Kvaerner sails on with its U.S. growth strategy, including Sea Launch, anchored across the continent in Long Beach, Calif. A joint venture with Boeing and Russian and Ukrainian firms, Sea Launch is the ultimate flexible facility: the first submersible satellite launch platform, which Kvaerner’s yards in Scotland and Norway converted from an oil-drilling platform. Sea Launch will stage its first liftoff from a Pacific Ocean site in international waters. Back in the cradle of U.S. shipbuilding, Rafdal remains characteristically upbeat. “We are following our plan as intended. And my family is very happy here. To us, Philadelphia has really been . . . what do they say? . . . the city of brotherly love. “Living in the U.S. will broaden my two children’s view, a very good thing. You can complain about globalization, but like it or not, it is here to stay.” SS

| This Issue | Site Selection Online | SiteNet | |

|---|

PLEASE VISIT OUR SPONSOR ? CLICK ABOVE

JANUARY 1999

JANUARY 1999

The Right Seafaring Stuff?

The Right Seafaring Stuff?