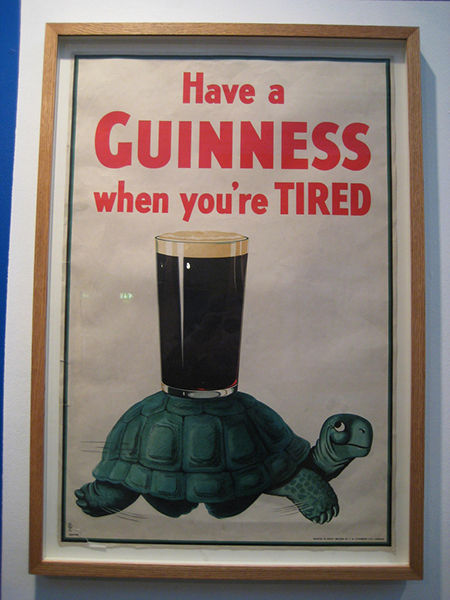

Everyone loves a tiger. Powerful, elegant – yet tricky to manage. Ireland was the Celtic Tiger during the boom of the ‘zeros. But now many economists are looking at the characteristics of a tortoise – slow, controlled, non-violent — as possibly more attractive.

In 2007-2008, after a decade of growth marred only by the global collapse of the dot-com bubble, the Irish economy started to implode. A “housing price bubble” that had seen property prices nearly quadruple in 10 years collapsed, contributing heavily to the trouble it now finds itself in, says Stephan Gerlach, deputy governor of the Central Bank of Ireland.

As in many markets across the world, as prices were increasing, financial institutions started lending recklessly, leaving themselves overexposed when the market peaked. With banks unable to lend, building halted, leading to widespread losses in a construction sector that had employed a fifth of Ireland’s population at the time.

A bailout of the banking sector coupled with high levels of government spending led to a collapse in investor confidence for Irish debt in 2010. This forced the Irish government to seek a bailout from agencies such as the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), causing domestic economic collapse.

The collapse brought an end to a decade of unprecedented growth that had seen Ireland fully transition from an agrarian backwater to one of the brightest stars in the Euro-zone.

The Boom Is To Blame

Although the causes and conditions of Ireland’s collapse are more complex than the summary given here, the end result is the same. After astronomical rises and two big falls, the country is ready for a period of sustained, incremental growth instead of a cycle of boom and bust. “I think many would be more happy with stability and sustainable growth,” says Peter Mindenhall, researcher for IPIN Global, a global property investment firm. “It was the boom that caused Ireland’s current problems.”

“Ireland has never had a single proper investment cycle. Everything has been associated with one bubble or another – first the dot-com then the property bubble,” adds Constantin Gurdgiev, an independent, Dublin-based economist and policy expert.

Photo courtesy: Bernard Goldbach (Flickr)

Ireland has now been in a recovery phase for nearly three years. According to some, it is making slow but steady progress. For example, Ireland was the only peripheral European economy to both increase revenue and cut spending last year, research company Capital Economics says.

This has enabled it to meet, and in some cases exceed, the fiscal targets and commitments the country had agreed as part of its bailout, says Gerlach, speaking at the Berlin Finance Lecture in January of this year. He concluded that Ireland had made good progress on restructuring its economy but that its economic state remains fragile.

And although the economy is fragile, Ireland is not necessarily a bad location for investment. According to the Irish Development Authority (IDA), the country’s low corporate tax rate, “native” English speakers (a term that would cause some supporters of the Irish language to bristle) and skilled, young work force all contributed to making it Forbes’s second-best place in Europe to do business in 2012.

A low corporate tax rate of 12.5 percent has already contributed to making Ireland the European home of multiple large, sunrise-economy multinationals such as Google, LinkedIn and Facebook. There is also a research and development tax credit of 25 percent attracting firms in scientific sectors such as pharmaceuticals. This has led to nine out of 10 of the top global pharmaceutical companies basing some operations there, the IDA adds.

The development authority also points to the Irish work force as an asset for firms looking to invest. Quoting the World Competitiveness Yearbook, it says that in fact Ireland is the number one location in the world for the availability of skilled labour.

But what it does not mention is that the same statistic is also an indication that many Irish face serious difficulties in finding work no matter how skilled they are. Current unemployment hovers around 14.6 percent.

Does Foreign Direct Investment Help?

There are reports that things are changing. Last year, the IDA estimates its clients – foreign direct investment (FDI) firms – created 6,570 new net jobs. This was particularly true in the information technology (IT) and computing sectors where firms such as Dropbox, PayPal and Apple either set up new operations or expanded current ones.

However, critics question the extent to which Ireland’s domestic economy benefits from FDI. A majority of the profits firms make leaves the country due to its low corporate tax rate, and overall employment from FDI has been negligible, says Gurdgiev. For one example, Facebook was granted 91 foreign worker permits in 2012 alone, although its Dublin office only employs 400 people.

With the Irish domestic economy still in a delicate state, it may be better if Ireland concentrates its attention on other areas such as reducing the burden of debt on consumers. However, there appears to be little appetite for this, he adds.

Like with most governments, there is a degree of statistical manipulation to help demonstrate that Ireland is on the right course and inspire consumer confidence. Around 200,000 people enrolled in state training programmes while receiving unemployment benefits are not counted in unemployment figures, despite not being in work, says Gurdgiev. “If you convince everyone the king has fabulous clothes on, everyone will see the fabulous clothes and no one will notice the king is naked. But unfortunately the king is naked and the economy has been destroyed by wrong efforts, policies and an economy dependent on one bubble after another.”

Others disagree. “Foreign multinationals are important in job creation. Not only through direct employment but also through those employed in the development of greenfield sites and the like,” says David Duffy, research officer at Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI).

Either way, it is very likely that Ireland will continue its investment-friendly policies, adds Duffy. The Irish economy is “open” – it relies heavily on imports and exports – and domestic trade continues to be weak due to a lack of consumer confidence and spending power. This means that it must continue to rely heavily on foreign investment.

Photo courtesy: Mike Lynch (Flickr)

Vulnerable to Variations

It also means that the country is extremely vulnerable to variations in the global market. For example, the Euro-zone crisis and the on-going debate over America’s “fiscal cliff” leave Ireland’s two biggest trade partners with issues that will affect both exports out of Ireland and inward investment into the country, according to financial consultancy firm, Grant Thornton.

“Italy has also been very quiet lately, which makes me suspect that there may be another bail-out request pending. And that would have a serious effect on the Irish economy,” adds Mindenhall.

Assuming that Ireland is not devastated by events outside its control, the country could also offer potential for investors in the medium- and long-term. What remains to be determined is the extent to which Ireland could recover in ideal global circumstances.

“I do believe that the Irish rate of growth could be well in excess of the European average and where we are now,” says Gurdgiev. “But that only compounds the egregiousness of the current situation. If we were like Greece, then okay – low aspirations, low hope, low outcome. But we are not like Greece. We are capable of competitively supplying goods and services into the global markets very competitively.”

Ireland’s return to the bond market last year was an early sign of optimism.

The country is scheduled to end the official programme of bail-out funding from international organisations later this year, and the positive re-entry into the bond market is a good sign of things to come, says Gerlach. However, debt is still high, and banks are not profitable, making it a very fragile economic situation with a small safety margin, he adds.

“Ireland is not at the end of the process yet,” says Duffy. “There is also a danger in saying we need to get back to where we were. Ireland will recover, but it will do so sustainably to growth rates that are normal for a developed country but lower than those we were seeing at the peak of the bubble.”

But no matter how far Ireland recovers, the characteristics of the dependable long-lasting tortoise may be something that the Irish population and foreign investors prefer.

Rob Denman is editor in chief and CEO of London-based Pathfinder Business.