On Sept. 22, a ceremony is planned on the banks of the Chattahoochee River in downtown Columbus, Ga. The occasion is the breaching of the Eagle and Phenix Dam, originally built before the Civil War to provide power to a long gone textile mill.

Local officials say it will not be a dramatic event with a huge crash and a wall of water descending downstream. Rather, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will be overseeing what will be a slow and systematic approach to dismantling the old dam.

After the Eagle and Phenix Dam is removed, the Corps will turn its attention upstream to the removal of the City Mills Dam, also dating back to the 19th century. It is all part of what the Corps is referring to as a river restoration project, formally known as the “Chattahoochee Fall Line Ecosystem Restoration Project.”

Shoal bass and certain types of plant life are expected to make a comeback once the Chattahoochee River is free-flowing again. But what the Corps sees as principally an environmental project, business and community leaders in Columbus see also as an ambitious economic development project that will pump money into the local economy and help transform a downtown.

“All the Columbus folks are working on this project because they understand that this is first and foremost an economic development project,” said John Turner, an executive with the W.C. Bradley Company. “It’s also a very important environmental project, but you couldn’t afford it if were not first an economic development project. You would never be able to raise the required money in order to do this.”

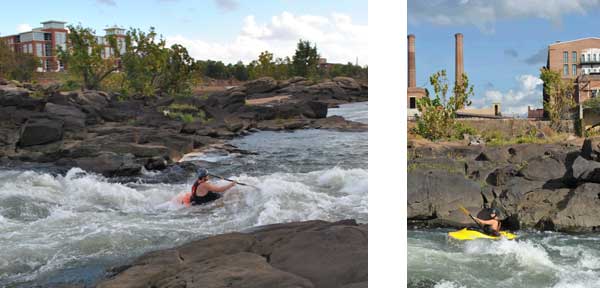

The “this” that Turner is referring to is the construction of what will become the longest urban whitewater park in the world, at 2.3 miles (3.7 km.).

“It’s enormous,” said Risa Shimoda, a whitewater design park consultant who has worked on design projects nationwide. “No one has been so ambitious as to redo two miles of river. It’s really awesome.”

According to a Columbus State University study, the finished course is expected to create 700 jobs, draw 188,000 visitors — 144,000 of those from out of town — and annually bring in $300,000 in lodging taxes and $1.7 million in sales taxes. A total economic impact is projected at $42 million per year, said Turner, who is credited by many in Columbus as being the brainchild and chief advocate for the project.

“John started asking questions about why we couldn’t use the river in a different sort of way,” said Mike Gaymon, president & CEO of the Greater Columbus Chamber of Commerce.

Olympic Level

Construction of a paved Riverwalk was begun in 1989 as a response to federally mandated sewage and water upgrades. And while the public soon accepted and used The Riverwalk for walking and biking, Turner felt that something was still missing.

“We still didn’t really yet have a truly activated riverfront,” he said.

The 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta provided the spark. A story commonly told in Columbus is that Turner was able to persuade the designers of the Olympic whitewater course on the Ocoee River in Tennessee to come to Columbus. After examining the stretch of river downtown, the designing engineers almost immediately concluded that Columbus would have been the better Olympic venue.

Turner holds that while the Ocoee offers excellent whitewater for kayakers and rafters, Columbus will hold a distinct advantage once the $23-million whitewater course is completed.

“We will have great whitewater here. We have a lot of drop in this river in the project area and we have a lot of flow,” Turner said. “More than 200,000 people visit the Ocoee River every year, but it’s only free-flowing from March to October. And then, in effect, they turn the water off. It’s not operational all the time. In our case, the only reason not to be in the river is because there is too much water, not because there is too little.”

And unlike the remote Ocoee, the Columbus v course will be in an urban environment, close to a downtown that has hotels and restaurants. The Riverwalk and bridges and loft apartments now being developed will provide spectators with the treat of being able to watch the action on the water.

“We’re convinced that we are going to be a really cool small town,” Turner said.

Many of the dams in the United States were built for water diversion, agriculture, factory watermills, and other purposes that are no longer being used. Because of the age of these dams, over time the risk for catastrophic failure increases. Such was the case in Columbus, where both aged dams were facing collapse. River restoration typically entails the removal of dams to allow for the free flow of water.

American Whitewater, a nonprofit organization comprised of conservationists and paddling enthusiasts, has lobbied for the removal of dams across the nation. Kevin Colburn, national stewardship director with American Whitewater, says dam removal has a positive economic impact.

“Putting water back into a river is a pretty powerful tool in restoring access. It’s a great tool for locking in recreation and economic value of a river and really highlighting it,” he said.

Officials in in Olympic National Park in Washington have begun what will be a the long process of dismantling the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams on the Elwha River. The largest dam-removal undertaking in U.S. history, the project could serve as an inspiration and a model for similar enterprises in other parts of the country, conservationists say. Deconstruction work begins next month (October) on dams on the White Salmon River in Washington and the Penobscot River in Maine.

Sixty dams were removed nationwide in 2010, according to American Rivers, a conservation organization. The list includes obsolete dams in California, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia and Vermont.

‘Unbelievable’ Development

If Columbus follows the pattern of what happens with urban whitewater parks, big changes are in store for the downtown in terms of real estate development and property values along the riverfront. Confluence Park in the Central Platte Valley neighborhood of downtown Denver Park in Colorado is viewed as the successful prototype where the redevelopment of an entire section of the city occurred.

“I think the biggest economic impact from the building of the park and the reclaiming of the river is the real estate impact on this neighborhood,” says Jonathan Kahn, owner of Confluence Kayaks. “Since I started the business here on the river 16 years ago, this neighborhood has just exploded as far as condo development and a retail development center down here. It was really a warehouse district 15 years ago.”

While the kayakers provide a focus to the river, they are not central to the real estate development that took place. Rather, it was a reconnection by city dwellers with the river itself, he said.

“It is not kayaking so much as reclaiming the river and making it friendly for people to recreate there. That is the biggest benefit of the parks,” Kahn says, “because the whitewater parks also attract people who are interesting in walking, biking or tubing. As a result, the real estate development down here by the river has really been unbelievable. It becomes a much more desirable place to put your home or your business because you have this recreational amenity that is right there.”

By all accounts, outdoor recreation has a huge economic impact on local economies in Colorado and nationwide.

A diverse mix of rafting outfitters, motels, fishing and birding guides, outdoor retailers, wineries, restaurants, chambers and other businesses all benefit. According to the Outdoor Industry Association, active outdoor recreation contributes $10 billion annually to the Colorado economy and supports 107,000 jobs. The Colorado Hotel and Lodging Association reports the state’s lodging industry employs nearly 47,000 people and generates more than $80 million in local and state tax revenues.

Nationwide, the Outdoor Industry Association reports that the outdoor recreation industry contributes more than $730 billion into the U.S. economy, supports 6.5 million jobs and is responsible for over 8 percent of the U.S. economy.

It is because of such economic impact that Sue Rechner, the president and CEO of Confluence Watersports, a kayak manufacturer that is expanding manufacturing operations in Greenville, SC., felt compelled to take on a U.S. senator from her state. A guest column written by Sen. Jim DeMint on the federal government’s land-acquisition plans did not adequately address the significant contribution of outdoor recreation to the U.S. economy, she said.

“In the mid-Atlantic states, including South Carolina, recreation contributes $67.5 billion to the economy and generates $8.2 billion in gear sales, $43 billion in trip-related expenditures and $8.3 billion in taxes; and it supports approximately 800,000 jobs for Americans,” Ms. Rechner wrote.

“Mr. DeMint’s statement that ‘Washington bureaucrats believe it’s more important to preserve grass and rocks for birdwatchers and backpackers than keep these local economies thriving’ seems to ignore the fact that these activities, as well as paddling, hiking, fishing and many other outdoor recreational activities fuel local economies, create jobs and continue to be strong economic drivers year after year.”

Confluence Watersports is in the process of moving into a new 300,000-sq.-ft. (27,870-sq.-m.) facility in Greenville. The move will combine work force and operations currently located in four buildings in two different locations into one facility. The more than $13-million investment will support expansion and is expected to generate 72 new jobs over the next five years. The company currently employs 425 people and is the ninth largest roto-molding facility in North America, according to Plastics News.

Fresh Perspective

Whitewater consultant Risa Shimoda says there may be as many as 70 whitewater park projects either under way or completed nationwide. Most are still in the planning stages and most will entail, like Columbus, physically building structure within the river channel so as to push and pull river currents in such a way as to make a better whitewater run for paddlers.

Industry professionals refer to this altering process as “river enhancement” and suggest that any environmental concerns are typically negated by the fact that whitewater advocates and designers are seeking free-flowing rivers, absent of dams as much as possible. Hence, recreation meets environment in a way that improves a river and the public’s outlook about a river.

“The kayakers, the paddlers, the rafters, they represent a very small percentage of those who enjoy the river and the use of the facilities,” Shimoda said. “But having activities on the river and colorful people to look at, well, it’s like the star on your Christmas tree. It makes people look to see what is out there and helps them appreciate that the river is there.”