Merger-contemplating executive No. 1:

Merger-contemplating executive No. 1:

“Can anybody stop us?”

Merger-contemplating executive No. 2:

“Hmmm . . . NATO?”

Citigroup does things big, as boldfaced by that humorous exchange, reported during 1998’s Travelers-Citicorp merger discussions. Just how big is obvious in Tampa.

“We have 9,400 employees in Florida, 2,500 in the Tampa area and 2,200 here in Citibank Center Tampa,” Teala Milton (below right), Citicorp North America vice president of Global Operations and Technology, matter-of-factly explains.

Another matter of fact, though, is telling. Citicorp’s 9,400 Florida employees almost exceed the total work force of headline-grabbing America OnLine. Indeed, Citicorp’s mammoth real estate presence in Tampa is the antithesis of some of the offbeat financial institutions that have sprung to life with a primarily electronic portfolio. Consider Atlanta-based Security First Network Bank, which serves customers in all 50 U.S. states, but has only two physical branches, one in Atlanta, one in Pineville, Ky. (est. pop.: 1,600).

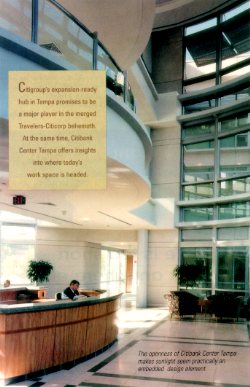

In sharp contrast, Citibank Center Tampa, which went online in March 1998, bespeaks critical mass. It spans 700,000 sq. ft. (63,000 sq. m.) in four three-story office buildings, plus a two-story, 138,000-sq.-ft. (12,420-sq.-m.) “amenities building” and a 50,000-sq.-ft. (4,500-sq.-m.) child-care facility. Not to mention the two 1,500-space, covered parking decks totalling 1 million sq. ft. (90,000 sq. m.).

In sharp contrast, Citibank Center Tampa, which went online in March 1998, bespeaks critical mass. It spans 700,000 sq. ft. (63,000 sq. m.) in four three-story office buildings, plus a two-story, 138,000-sq.-ft. (12,420-sq.-m.) “amenities building” and a 50,000-sq.-ft. (4,500-sq.-m.) child-care facility. Not to mention the two 1,500-space, covered parking decks totalling 1 million sq. ft. (90,000 sq. m.).

Citibank Center is so large, in fact, the Tampa Post Office gave it its own postal code.

The unique ZIP code is appropriate, since Citibank Center Tampa is the shape of things to come in Citibank real estate – and, likely, in much of today’s corporate work space. At the same time, it provides perhaps a glimmer of the US$70 billion Citigroup merger’s shakeout.

The Regional Real Estate Solution

To be sure, the massive Tampa center symbolizes a major shift in Citicorp’s site selection strategy.

“A lot of Citicorp’s major new innovative concepts were put into place down here,” explains Joseph McCarthy, Citicorp North America vice president of Corporate Realty Services for the USA.

Citicorp’s on-the-ground strength has made it consumer banking’s only successful global brand. Yet only a few years ago, Citicorp suffered from an operational glitch rooted in geographic limits. Despite Citicorp’s vast global reach, control over non-U.S. operations seemed to invariably revert to the New York City headquarters.

“Most everything used to be controlled in New York, or if not there, in London,” explains Kenneth Sommer, Citibank North America vice president and chief financial officer for Global Operations and Technology.

That centralization, Citicorp’s top management now acknowledges, hampered customer service. The global network was, in fact, a loose affiliation of branches, with varying systems and service delivery. Moreover, some customers had grown wary of dealing with service facility-based personnel often operating with data one step removed from the on-the-ground action.

In short, it was globalization that wasn’t truly global.

Citicorp attacked the problem through a decentralization strategy dubbed “regional windows,” the raison d’?tre for its huge Tampa presence. In 1996, Citicorp began opening three of those windows, ultimately setting up regional service centers in Tampa, serving the Americas, in Lewisham, England (near London’s Canary Wharf), serving Europe, and in Singapore, serving Asia.

And this time out, Citicorp backed its location strategy with substantial, long-term real estate commitments. That’s evident in the 127-acre (51-ha.) site it acquired in Tampa, which won out over numerous other amorous suitors, most notably Atlanta and Dallas.

“Even with our 700,000 sq. ft. in place here, we still have development entitlements to another 35 acres (14 ha.) on this campus, so we can grow our total space out to 1.5 million sq. ft. (135,000 sq. m.),” McCarthy says. “And we can expand our 3,000 parking spaces to 5,828.”

Business Units Head South

As Citicorp’s Tampa real estate illustrates, the regional windows are much more than cosmetic. With top management’s strong backing, Citicorp’s regional centers have emerged as significant players, unshackled by the ugly-stepchild status that hobbles many other firms’ regional operations. The Tampa center, for example, now serves as the headquarters base for two major divisions overseeing roughly 80,000 of Citigroup’s some 164,000 worldwide employees:

- Global Operations and Technology, Citicorp’s back-office operation, which handles functions such as processing financial transactions and developing software to bolster trading operations; and

- Business Services, the company’s shared-service arm, which provides Citicorp’s worldwide facilities with real estate services, security and insurance, and goods procurement.

Granted real global clout, the Tampa center also now handles all Latin American client service; operations in Latin-based facilities handle only settlement expediting. Using cutting-edge technology, Tampa-based customer service staffers access information that reflects on-the-ground Latin American realities. Consequently, clients interfacing with regional centers like Tampa’s now get even better information than the data Latin facilities provided.

The Tampa regional center has also strengthened Citicorp’s Latin hand. “We’re now Venezuela and Mexico’s largest provider of securities,” Sommer offers by way of example.

Spooked by economic uncertainties, some banks have pulled back in Latin America. Citicorp, though, has kept the expansion heat on. Its recent acquisition of Buenos Aires-based Banco Mayo, for example, made Citibank Argentina’s second-largest private bank, with a 106-facility network and $5.7 billion in deposits.

“At a time when many other private sources of financing to Latin America and the Caribbean are increasingly cautious, we are increasing our already extensive lending activities,” says Naveed Riaz, Citibank division executive for Latin America.

Spearheaded by the Tampa operation, that expansive aggressiveness has paid off, making Citibank Latin America’s biggest foreign-based bank, according to the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. With $23.5 billion in assets in Latin American facilities in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela, it’s 20 percent larger than either Spain’s Banco Santander or the Bank of Boston, its two top rivals among foreign-based banks in Latin America.

BELOW: Citicorp Center’s cost-effective functionality appeals to

architectural aesthetes and Spartan-minded shareholders alike.

First Quarter Confounds Cynics

First Quarter Confounds CynicsThe regional center location strategy got some potent reinforcement in Citigroup’s first-quarter 1999 financials. Confounding the many skeptics anticipating a stumble from the newly joined behemoth, Citigroup’s $14.7 billion in revenues yielded record first-quarter 1999 earnings of $2.42 billion, a 12 percent increase from 1998. That topped all financial services firms and also eclipsed the most recent profits posted by General Electric, General Motors and Microsoft.

The Tampa center’s Americas region put up particularly strong numbers: Citibank North America’s $75 million income marked a 200 percent upswing. And Citigroup’s first-quarter Latin American revenues of $48 million signaled 12 percent growth, part of international revenues’ 20 percent growth to $281 million.

Analysts, however, caution against premature conclusions.

“Citigroup first-quarter numbers are noteworthy, but they don’t yet speak to its integration,” says Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analyst David Berry. “Now, the big question is whether they can duplicate it.”

Complementary Portfolios

For the moment, such post-merger questions remain obscured in a cloud of conjecture that’s as pea-soup-thick as the early morning fog shrouding Tampa today.

“This is a big, big organization,” Sommer says. “We’re taking small steps to slowly bring it all together.”

It’s big, all right. With its official approval on Oct. 8, 1998, Citigroup became the world’s biggest financial institution, No. 7 on the Fortune 500, with $690 billion in assets and facilities in 100-plus nations. Its market value of $148.8 billion exceeds Credit Suisse Group, Charles Schwab and Merrill Lynch combined.

Aligning two giants of that scale through lightning-quick moves would likely smack of dangerous overreaching. In fact, by providing some badly needed short-term predictability, it may be a godsend that Citigroup has two “Co-CEOs” – former Citicorp CEO John Reed and former Travelers CEO Sanford Weill, who’ve made it clear that they don’t plan to relinquish any pre-merger responsibilities.

But while it may seem to move glacially, this merger of equals is not like some other financial services mergers, which, by necessity, have turned into cost-cutting layoff machines.

“One thing to understand in all this,” says Citicorp North America Operations Director John McEachern, “is that there’s not much overlap between the old Citicorp and the old Travelers.”

Indeed, their very differences made one of the most compelling arguments for the Citicorp-Travelers fusion. Within their respective real estate portfolios, each brought complementary strengths to the Citigroup party: Citicorp supplied its formidable global banking network, while the Travelers contributed its broad U.S. system of insurance and stock-brokerage offices.

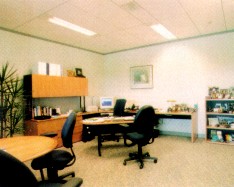

BELOW: Office environment leader Steelcase considered the project important enough to specifically design a new furniture line for the Tampa project.

Expansions and Contractions

Expansions and Contractions

Uncertainties over how those portfolios will align will eventually dissipate – though likely nowhere near as rapidly as Tampa’s rush-hour fog, which has vanished by mid-morning.

To be sure, despite the players’ overall synergies, the merger is spurring some downsizing in the combined Citicorp-Travelers real estate portfolio. Citigroup is regionally consolidating its worldwide call centers and other back-office functions, unifying its New York and London locations and continuing the consolidation of Citibank and Salomon Smith Barney facilities. Consequently, in what officials call “the integration of activities,” Citigroup has cut 10,400 positions, roughly 6 percent of its worldwide work force, part of its drive to cut costs by $2 billion by the end of 1999.

Citigroup’s major presence in Tampa, however, looks a good bet for continued growth. Announced by Citicorp in the pre-merger days of August 1998, Citigroup’s 1,500-employee expansion in Tampa is still running on schedule, says Robin Ronne, Tampa Chamber of Commerce/Committee of 100 economic development director, roundly acknowledged by company officials as one of Citicorp’s most avid recruiters and most fervent champions. Already, Citibank Center Tampa has landed one major post-merger shift, becoming Citigroup real estate’s operational base. Joseph Sprouls, former Travelers Investment Group first vice president and general counsel, is relocating to Tampa to head Citigroup’s newly formed corporate real estate division, working with two of the industry’s most widely respected pros: Andy Bessette, Travelers’ Hartford, Conn.-based corporate real estate and services vice president, and Stephen Binder, Citibank’s New York-based vice president and global planning director.

The Tampa Real Estate Prototype Adds Punch

But perhaps the strongest factor favoring expansion in Tampa is the definitive real estate design Citicorp implemented in its Hillsborough County center.

“Citibank Center Tampa is the prototype year 2005 corporate campus model for Citibank worldwide,” McCarthy says. “It takes into consideration today’s business needs and looks ahead to future needs. What we’ve created is a flexible work environment that could easily serve any of our corporate divisions.”

Indeed, the $250 million Tampa campus likely represents where many workplace configurations are headed. And there’s some irony in that. After all, the Citigroup merger took numerous hard analytical hits, some generously garnished with defensiveness. A Baltic Banking Group report, for example, called it “the mating dance of dinosaurs, not the start of a new bull market move.”

Yet for all the reflexive bashing they’ve taken, corporate giants are still usually the bell cows in cutting-edge facility design. After all, they can afford to invest in new workplace strategies. And when there’s a productivity payoff, they’ve proven as willing as they are able to do just that.

Citibank Center Tampa reflects that willingness, incorporating many leading-edge workplace ideas.

Vivian Loftness, for example, chairwoman of Carnegie Mellon University’s Architecture Dept. and among today’s most articulate workplace reformers, deplores the “preset options” embedded in much contemporary work space, which stifle integration and productivity, she contends. “If we’re going to truly integrate, we’ve got to move away from blanket workplace servicing and start talking about investing in flexible infrastructure,” Loftness says.

Citibank Center Tampa answers that flexibility challenge.

“In our four office buildings here,” McCarthy explains, “we have 42,000-sq.-ft. (3,780-sq.-m.) floor plates, all with flexible floor systems, with the plates lying perpendicular to one another. Plus, all the space is pre-wired, with fiber-optic cabling and raised flooring throughout.

“So if another business unit were to move in here,” McCarthy says, “we could reconfigure all the space overnight.”

BELOW: Even private offices in the Tampa Center contain space designed for collaborative work.

A ‘Mini-City’ in ‘Citi-Space’

Few real estate infrastructures can match that uber-flexibility, particularly over such vast square footage.

And for all its massiveness, the Citibank Center’s design works something like a Mobius strip. It pulls the space together, in turn pulling people in. The space is broken down to human scale by a holistic design. Jeff Jensen, who along with Eddie Abeyta, served as HKS Architects’ project designers for Citibank, calls it “a sensitive arrangement of simple, like building forms master-planned linearly around a pedestrian circulation network.”

The center is thematically unified by a “mini-city concept.” Known as “Main Street,” the pedestrian network’s linear spine runs throughout the complex, with clear-glass covered walkways (open on the sides) connecting the five buildings. Main Street also runs through the center’s “entry joints,” large cylindrical areas that serve as gathering spots (or “town squares”), plus handling reception and security functions.

Similarly, human scale rules the interiors.

“Citibank requested a different office feel, a departure from the standard, rectangular-shaped, six-person-workstation configuration,” says HKS interior designer Paula Carter. McCarthy calls it “Citi-space,” a company planning guideline for office layouts that “emphasizes both flexibility and departmental synergies.”

By whatever name, the Tampa Center’s interiors are far more open than most workplaces. From almost anywhere, one can spy the panoramic views outside, where small manmade lakes dot Sabal Corporate Park’s gently rolling landscape. A vast but unobtrusive window network bathes the space in natural light – so much so, that the sun seems practically an embedded design element. If, as Goethe once said, “architecture is frozen music,” this, then, feels like fresh-frozen Florida sunshine.

The interiors are also finely detailed. Hallways, for example, feature extra-wide turns and paths to allow for the robotic carts that, like so many corporate R2D2s, deliver employee mail.

At the same time, though, Citibank Center Tampa is light years removed from the waterfall-in-the-atrium excesses of the 1980s, when corporations built horrendously cost-ineffective monuments to themselves. First-class and inviting certainly describe the Tampa Center; but lavish, it’s definitely not. However well-designed, the space retains a solid, cost-effective functionality that even the most Spartan-minded shareholder could love.

And in that, the Tampa Center embodies the new, less-is-more ethic increasingly ruling American corporate space.

Investing in Human Capital

Citibank Center’s smart-minded frugality isn’t a new tack. In fact, Citicorp’s tough-minded cost-reduction program, implemented after bad loans staggered the firm in 1991, substantially increased projected post-merger savings. “We’ve become so efficient in our real estate asset utilization that vacancy within our U.S. portfolio is 1 to 2 percent,” McCarthy says.

Instead, what’s different here in corporate space use is Citicorp’s strategy for investing the capital saved by rejecting over-the-top ornamentation. It’s added huge value by investing in an employee-friendly environment, a vital concern, given today’s airtight labor markets.

“What we’ve tried to do is become an area employer of choice,” Milton explains. “We’ve tried to create space that’s timeless, functional and helps employees balance their work and personal lives.”

Ah, balance, that hot workplace buzz word. Increasingly, employees are looking for more than paid vacations, 401Ks and standard-issue health plans. That’s precisely why Citibank Center’s on-campus amenities building offers a broad gamut of employee-pleasing niceties:

There’s an exercise club with a wooden-floored aerobics area, a weight room, cardiovascular training machines and locker rooms. (An outdoor exercise area with a top-of-the-line running track sits nearby.) The facility also features a subsidized cafeteria serving breakfast and lunch, a medical center providing testing and consultation, an employee banking center and a large sundries shop.

The amenities building even houses a concierge, who assists visiting Citigroup employees utilizing the conference center on the facility’s second floor. Easily reconfigured, the center’s rooms feature tiered seating, raised flooring, an array of audiovisual aids and even a storeroom for visitors’ luggage. It’s space that could be a major plus in facilitating the cross-selling the Citicorp-Travelers merger envisioned.

Building at an ‘Amazing Pace’

Citibank Center Tampa is all the more remarkable in light of the divergent processes that drove it. On one hand, Citicorp wanted to carefully craft the optimal expansion-ready site. On the other, it wanted warp-speed construction.

“Florida has developments of regional impact (DRI), which allow office projects exceeding 300,000 sq. ft. (28,000 sq. m.) to locate on pre-permitted DRI sites,” explains Dave Kemper, vice president and Florida manager of civil/site engineering for Dames & Moore (www.dames. com), which handled Citi Center’s civil engineering and site procurement.

“Originally, the DRI provided for project build-out by 1999. Citicorp wanted more time to build out the acreage,” Kemper continues. “Consequently, we were able to amend the DRI to add five more years to the entitlement.”

While such issues were unfolding, Citibank was implementing its $338,309 in Quick Response Training grants from Enterprise Florida.

Then things moved very quickly. March 1997’s groundbreaking set off a cast-of-thousands construction scenario straight out of a Cecil B. DeMille epic.

“The pace was amazing,” explains Terry Davis, project superintendent with Hardin Construction (www .hardinconstruction.com), which built Citi Center. “We had nine different buildings going up at the same time, with up to 1,000 people on site each day for 12 months. In addition, throughout the entire process, we had record-breaking rainfall.”

Despite those obstacles, a year later the project came in on budget and on time. And despite the hurly-burly, Citibank Center successfully links real estate, human resources, finance, information technology and strategic planning in a single strategic concept. In fact, Tampa Bay’s real estate industry named it 1998’s “outstanding special-use private-sector building” at ceremonies hosted by the National Assn. of Industrial and Office Properties’ local chapter.

“Citicorp has a very strong design and construction staff, and we had great teamwork among all the service providers,” Kemper explains.

Similarly front-loaded with urgency, Citicorp announced its 1,500-employee Tampa expansion only five months after the regional center’s opening. The Hillsborough County Commission provided a potent draw for the expansion, agreeing to refund $1 million in impact fees over four years if Citicorp creates 1,000 net jobs paying at least the country average of $25,353.

Locating for Labor

If you build it, though, no matter how well, and they don’t come, . . . well, update your resume.

And at least on paper, locating for labor would seem to be a major concern in Tampa Bay, where unemployment regularly hovers near 3 percent, some 25 percent below U.S. rates that are the lowest in 30 years.

Martin, however, says, “Most expanding companies also face tight labor situations, but we’ve done very well, in part by being an employer of choice. Tampa has been an excellent labor market for us.”

Citicorp executives also say potential labor worries have been soothed by Tampa Bay’s hefty stream of newcomers, drawn by the area’s strong economy, Gulf Coast beaches, reasonably priced housing and low living costs. Tampa Bay will be one of the 10 fastest-growing U.S. metros through 2000, according to U.S. Dept. of Commerce data.

Finally, plain old location, location, location has abetted Citibank Center’s recruitment and retention. The center lies in East Tampa, a spheroid-shaped business location hotspot between U.S. 301 and I-75 that’s also attracted the likes of Pharmerica, Progressive and UPS.

With Tampa lacking metro rapid transit, driving distance becomes more than a casual phrase. East Tampa’s location, however, fits that bill, with five major roads intersecting the area: I-4, I-75, U.S. 301, State Road 60 and the Leroy Selman Expressway. A short drive away lie a number of solid labor bases, including Brandon and New Tampa. Then there’s the University of South Florida (USF). With some 28,500 of its 35,000-plus students in Tampa, USF has quietly become one of the largest U.S. public universities, plus a prime Citibank Center labor pool.

East Tampa’s economic revitalization has been so successful, in fact, that popular Tampa Mayor Dick Greco plans to repeat the development plan throughout the city, a move that reflects metro-area interdependence. “Dick Greco set a tone in the city that Hillsborough County has tried to follow,” Kemper says. “With their real estate backgrounds, Mayor Greco and Robin Ronne have both been great cheerleaders in facilitating business expansion in Tampa Bay.”

A Change is Gonna Come

Interdependence is also the name of the game for the evolving Citigroup -which thus far is mostly a merger that isn’t.

Undoubtedly, however, change will rattle the landscape. For the moment, the financial service industry enjoys a number of one-off upswings, including the wider gap between market interest rates and rates paid depositors; lower premiums for deposit insurance and smaller requirements for loan losses.

Undoubtedly, Co-CEOs Weill and Reed are already looking hard for answers for when those non-recurring windfalls run dry. Some of them, it seems, will likely come from examples like the Tampa center.

“We’ve got a lot of shared resources here now,” McCarthy says. “A lot of walls have come down.”

SS