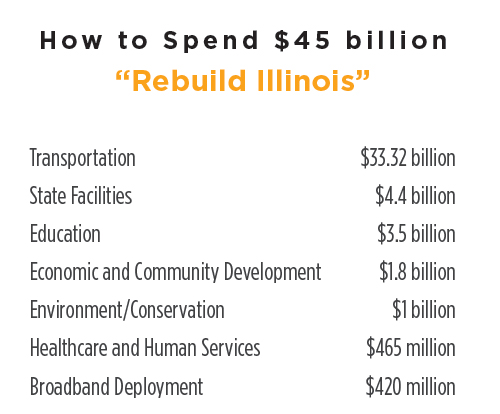

Infrastructure being a key component of economic development, Illinois has launched a $45 billion, multi-year program to upgrade its roads, bridges, railways, schools and other state-owned facilities.

“Rebuild Illinois” is a pet project of Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who says the program also will put some 540,000 people to work, making it what he calls “a job creation plan the likes of which our state has never seen.” The sprawling initiative was approved with unusual bi-partisan support by the notoriously combative Illinois legislature. It’s the state’s first capital spending plan in a decade.

“We view this as a down payment,” says Michael Pomerantz, head of real estate at the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO). “We are creating an environment to have additional investment come into the state through private corporations and public corporations wanting to expand and relocate here having seen our commitment to rebuilding the state.

“This can help local communities throughout Illinois with such things as site readiness and shovel readiness,” Pomerantz continues. “We have sites that are well located, but there may be an issue related to access or utility tie-ins or other things.”

Through Rebuild Illinois, local communities will have the opportunity to apply for grants that could go toward efforts to alleviating such problems.

“It will help them clean up some sites that might need it to make them more viable for private investors to come in and scoop them up,” Pomerantz says.

About three-fourths of Rebuild Illinois — $33.3 billion — will go toward transportation infrastructure, which includes not only roadway expansions and repairs, but also mass transit, passenger rail, ports and other projects. In a sense, it’s playing to the state’s strengths as a centrally located transportation hub.

“Illinois is a transportation haven. Our location is one of the huge advantages we have,” says Mark Denzler, president of the Illinois Manufacturers Association, which lent its support to the plan.

“We have thousands of miles of highways and Interstates,” says Denzler. “We are the only state that has all seven Class I railroads coming through it. The Port of Chicago is the fifth-busiest port in the United States. We have O’Hare in Chicago and international trade zones. So, getting this done is critical.”

Most of the infrastructure projects will be identified by the DCEO as the program unfolds, based on grant submissions. But the legislation did stipulate upward of 3,000 ventures, some of which are underway already. They range from the ambitious to the seemingly mundane. A few examples:

- Road construction relating to the Chicago Region Environmental and Transportation Efficiency (CREATE) program: $400 million

- Chicago to Rockford Intercity Passenger Rail expansion: $275 million

- Capital improvements for the Hartman Lane and Central Park intersection in O’Fallon, a city of 29,000 along I-64, just east of St. Louis about five miles from Scott Air Force Base: $1.6 million

- Acquisition, design and construction of a bicycle trail in Calumet Township, just south of Chicago: $1.5 million

- Storm sewer improvements in Arlington Heights: $1 million

- Building a city fiber network in Decatur, east of Springfield: $800,000

- Port Development at Cairo, a town on the Mississippi River in extreme southern Illinois: $750,000

- Infrastructure improvements to Gordon Moore Park in Alton, near St. Louis on the Mississippi: $600,000.

The Illinois Department of Transportation informed Site Selection that more than $5 billion will go toward new roads, road extensions and widenings as opposed to mere repairs and maintenance. Department spokesman Paul Wapple says such allotments include $1.2 billion to add auxiliary lanes, among other improvements, to a 16-mile (25-km.) section of I-80 below Chicago, currently a high-growth area.

Darin Buelow, global location strategy leader in Deloitte’s Chicago office, says expansions such as that can turn out to be game changers.

“Projects that involve extending a highway that doesn’t exist today or taking a two-lane road and turning that into a four-lane limited access highway could change the economics of a particular region and may open sites to development,” Buelow says. “It can change traffic patterns and influence where people decide to live and which housing developments get built. These highway projects can shift where companies go, where retail and commercial establishments get built. New roads are a big deal.”

“These highway projects can shift where companies go, where retail and commercial establishments get built. New roads are a big deal.”

To pay for Rebuild Illinois, the state legislature approved a significant tax increase of 19 cents on a gallon of gas. The state cigarette tax went up by $1 per pack, and there’s a new tax on electronic cigarettes. Proceeds from a massive expansion of gambling operations and betting opportunities are expected to eventually yield $350 million annually.

State finances are a sore subject in Illinois. A years-long stalemate between former Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and the majority-Democratic legislature resulted in a huge backlog of unpaid bills. Along with the drag of staggering pension obligations, the state’s debt is expected to reach some $19 billion by 2025. Faced with that reality, legislative opponents of Rebuild Illinois balked at the idea of a $45 billion public undertaking funded through tax increases.

But Chris Setti, CEO of the Greater Peoria Economic Development Council and a member of the Board of Directors of the Illinois Economic Development Association, believes these particular tax hikes are unlikely to scare off businesses.

“Businesses want to spend as few dollars as they have to in order to make the product that people will buy, and they’re fairly agnostic as to how those dollars are allocated. If we can lower their cost by making it easier for them to transport goods and making transportation more efficient, they’ll recognize that.”

Still, with Illinois saddled with the lowest credit rating among all 50 states, Deloitte’s Buelow says its wretched finances could prove to be a drag on investment.

“If the ongoing fiscal situation in Illinois continues,” he says, “to some companies that means the state will have to raise taxes in the future, either at the personal level or the corporate level or both. They see that as a risk to their organization, and it can make them question whether to expand in Illinois. It’s not all companies, but some do see it that way.

“If I could wave a magic wand to make Illinois more competitive,” Buelow adds, “I’d use it to chip away at that debt and eventually retire it through

any number of changes, be they reductions in spending or restructuring of the pension liability. That’s Illinois’s biggest impediment. No question about it.”