Promote Openness

Two years ago, the Dubai Ports World controversy led to a lot of soul-searching in Washington, not to mention a lot of anxiety around the globe.

Fast-forward to 2009, and there is a clear message coming from the nation’s capital. “America is open for business,” a top U.S. Commerce Department official declares. “We are the most open major economy in the world, and we welcome foreign direct investment.”

While that statement may not seem extraordinary – after all, almost every country welcomes FDI – the path that the United States took to go from a broken deal to a new era of investment promotion was not easy.

Invest in America – an initiative of the Commerce Department – was established in 2007 to “demonstrate clearly to the world that America is the best place to invest and the safest place to invest in the world,” says David Bohigian, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Market Access and Compliance and the creator of the Invest in America program.

“In the aftermath of the Dubai Ports World debate, that fact was called into question,” Bohigian tells Site Selection. “It looked bad to the world. It made us look like we didn’t want foreign investment.”

What followed was an extensive rewrite of CIFIUS (Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States) legislation and the launch of America’s first-ever, focused strategy to promote FDI.

“If we do not play an active role in promoting inward investment, we are at risk of having our investment climate perceived around the world only by the occasional difficulty,” said Franklin Lavin, Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade, at Invest in America’s debut in March 2007.

One “difficulty” captured the most attention: the controversy that erupted over the proposed Dubai Ports World deal in February 2006. At issue was the pending sale of port management businesses in six major U.S. seaports to a company based in the United Arab Emirates. Critics said the deal would compromise national security, even though President Bush argued that UAE was a political ally and that DP World in no way compromised America’s safety.

After a key U.S. House of Representatives panel voted 62-2 to block the deal, and U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer of New York added amendments to a Senate bill to prevent the sale, DP World relented. On March 9, 2006, the company said it would turn over operation of the ports to a U.S. entity. DP World eventually sold the port operations to AIG’s asset management division, Global Investment Group.

The aftermath reverberated around the world, as suddenly the openness of the United States to FDI was called into question. Would the nation treat other allies this way? The question, once unthinkable, was at least being asked.

The result was a dramatic policy offensive aimed to restore the United States’ reputation for openness. President Bush issued an historic statement on May 10, 2007: “The United States has a longstanding commitment to open economies that empower individuals, generate economic opportunity and prosperity for all, and provide the foundation for a free society. Economic freedom, supported by the rule of law, reinforces political freedom by encouraging and supporting the free flow of ideas. To continue the advance of liberty and prosperity, my Administration will work vigorously to promote open investment policies and free trade on a level playing field.”

He added: “The United States unequivocally supports international investment in this country and is equally committed to securing fair, equitable and non-discriminatory treatment for U.S. investors abroad.”

For the world’s largest investor and largest recipient of investment, this was an extraordinary statement – but it was also an admission that more work needed to be done at home to ensure that such pledged openness would be more than words on paper.

Bush then moved quickly to sign into law, on July 26, 2007, the CIFIUS reform legislation that streamlines the process by which foreign direct investment into the U.S. is reviewed for national security reasons.

Bohigian says these were key developments in reinforcing the message that America meant business.

“Invest in America communicates that we are open to FDI from around the world,” he says. “Dubai Ports World happened in 2006. Invest in America happened in 2007. The President’s statement came out in 2007, and CIFIUS reform became effective in late 2007. We think that the legislation passed by Congress and signed by the President helped bring CIFIUS into the 21st century.”

Bohigian notes that less than 10 percent of all cross-border transactions are reviewed by CIFIUS. “And the committee does not review greenfield investments,” he says. “In 18 years, we had only one real hiccup.”

Bohigian says people should know that “in the long history of CIFIUS, we have blocked only one deal – out of thousands of transactions. They have all gone through. Dubai Ports World decided voluntarily to divest. It doesn’t prove we are closed; it only proves we messed one up.”

In fact, argues Bohigian, the whole ports deal controversy obscured the real “reality” about FDI in the United States – the fact that “America is the best place for risk-adjusted return in the world.”

In 2007, the U.S. garnered $238 billion in FDI, most in the world. In that same year, 5.3 million workers were employed by foreign companies on American soil.

“FDI jobs pay 25 percent higher in wages than regular U.S. jobs,” says Bohigian. “They help strengthen manufacturing. Over 30 percent of FDI jobs are in the manufacturing sector.”

A case in point is the world’s largest maker of fiberglass pipes. Michael Olivier, president of Future Pipe USA, an entity of Dubai-based Future Pipe Industries, says that his company continues to expand its capital investments in the U.S.

“While we intend to close our plant in Mississippi and relocate the capacity, we will expand a pipe production line in Houston,” he tells Site Selection. “Future Pipe is the largest privately owned company in the fiberglass pipe business in the world. Obviously, having been the largest player in the last five years, much of the growth in our industry has been in the Middle East. But the company’s next step is to expand in the Americas.”

With $1.2 billion in sales in 2008, plus a large backlog of orders for 2009, Future Pipe is positioned to grow its business in North and South America, says Olivier, formerly the chief economic development officer for the state of Louisiana.

“The doubling of the capacity in our Houston plant will take us about a year and a half,” he says, noting that the expansion will include a 120,000-sq.-ft. (11,148-sq.-m.) facility. “We feel that it is an appropriate time to expand. We have a niche in the medium-to-high-pressure pipe business here in the U.S.”

Ultimately, Olivier says, “we will re-establish a large-diameter pipe plant in the Americas. We will be looking for a site. One of my charges from the owners is to be constantly looking for site selection. If we get a contract that will bring us two years of production, we will make an investment of 100 to 200 jobs and $15 million to $20 million typically.”

Olivier can’t say when such a search might be completed, but, he adds, “Our owners are able to make decisions quickly.”

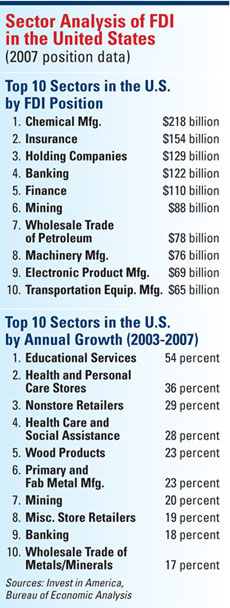

One reason that international investors like Future Pipe have their eye on the U.S. is that chemical manufacturing leads all other sectors in total FDI, topping second-place insurance, third-place holding companies and fourth-place banking.

The top sectors in the U.S. by growth, from 2003 to 2007, are educational services (up 54 percent in total FDI), health and personal care stores (36 percent), non-store retailers (29 percent) and health care and social assistance (28 percent).

In terms of greenfield projects, from 2003 to 2007, the top FDI sectors are software and IT services (444 projects), automotive components (316 projects), financial services (263 projects) and industrial machinery and equipment (222 projects).

In terms of FDI share of employment through 2006, South Carolina leads all U.S. states with FDI accounting for 7.9 percent of its jobs, followed by New Hampshire (7.4 percent), Connecticut (7.1 percent), Delaware (7.0 percent) and Hawaii (6.6 percent).

New Mexico, led by President-elect Obama’s Commerce Secretary nominee Gov. Bill Richardson, was low on that list. But its star has been rising in recent years, with projects such as the large new photovoltaics plant near Albuquerque from Germany’s Schott Solar.

Richardson, known for his longstanding record of working with Mexico, has traveled the world on behalf of the state in order to recruit business investment. His 2008 trips to Europe and the Middle East focused on the clean energy sector that is so much a part of the incoming Obama administration’s economic development focus for the nation. (On Jan. 4, Gov. Richardson withdrew his name from consideration for the Commerce post, citing the potential delay in the confirmation process caused by an ongoing federal inquiry into how a political donor landed a lucrative state contract. In a statement, Obama said a new nominee would be named quickly, but that he still anticipated Richardson eventually playing a role in his administration. -Ed.)

The Commerce Department knows that the U.S. could do better. That’s why outgoing U.S. Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez released a report Oct. 29 on the U.S. litigation environment and trends in FDI flows into the United States.

His report states that high litigation costs impede the country’s ability to compete with other nations, and the secretary recommended “sustained efforts to bring these costs in line with those of other nations.”

Bohigian says his department will continue to support reforms in this area, adding, “America has one of the strongest legal systems in the world, but it could be improved.”

Site Selection Online – The magazine of Corporate Real Estate Strategy and Area Economic Development.

©2009 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.