he seven states comprising the southeastern corner of the United States already are home to 30 of the nation’s 103 nuclear power reactors. The relatively clean and inexpensive power they produce has played a key part in the region’s industrial development prowess. Today the South is preparing to play an even greater role in the nuclear power industry’s resurgence – and is willing to pay for the privilege.

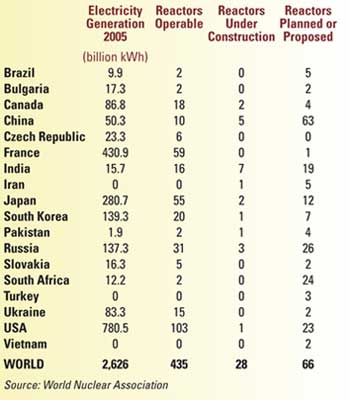

Of the 28 new nuclear reactor units expected to file applications with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission through 2009, half are in the Southeast. The late May restart of Tennessee Valley Authority’s Browns Ferry 1 reactor makes it 15 of 29. According to interviews conducted by Site Selection, the horizon is aglow with opportunity.

“The two most important factors regarding electric service are reliability and cost per kilowatt- hour,” says Jeff Forsythe, senior consultant at McCallum Sweeney. “The Southeast has always been known for low- cost power and supply.” If new nuclear units are built, he says, “I think it will be a great selling point for the Southeast.”

Though it’s just one component of an overall cost comparison, he says it could have a big impact. And the general trends are converging in its favor.

“The Southeast is going to be growing, and both population and manufacturers are going to need power,” says Forsythe. “The ability to offer lots of low- cost power is an advantage. Other regions are struggling to provide power at an affordable price. We’ve been in regions where the rate was outrageously high, at 12- 16 cents per kilowatt- hour. It blew me away.”

“We have to add baseload generation in the 2010 to 2016 time frame, whether nuclear or coal,” says John Sell, spokesman for Southern Company subsidiary Georgia Power. He explains that incipient industrial development, while good, is not the motivator: “We have to have it just to keep up with the demand in the state of Georgia.”

Yet the connection between affordable and reliable power and future economic development is tangible.

“I think they go hand in hand,” says Randy Hutchinson, senior vice president of nuclear business development and new plant activities for Entergy Nuclear. “We have a retired CEO here who has a saying – ‘No power is more expensive than no power.’ “/

Hutchinson knows whereof he speaks when it comes to industrial end users and electricity, having preceded his 35 years with Entergy with five years working for the Ingalls Shipbuilding Nuclear Submarine Program in Pascagoula, Miss. He was involved in the original cycle of site selection for nuclear plants.

“In the ’70s, we had very few nuclear sites that had been qualified or certified as a nuclear site,” he says of his days with Mississippi Power & Light, before it became an Entergy company. But water was important, as it is for any power plant. “In Mississippi, we looked along the Mississippi River, from the northern to the southern boundary.”

Searching above the 100- year flood plain brought into plain view two sites: the one known today as Grand Gulf (a leading candidate to be the nation’s first nuclear plant expansion site in 30 years, which received its early site permit from the NRC in April) and another site at Fort Adams, south of Natchez. “We bought property for both of those, and ultimately made the decision to site at Grand Gulf,” says Hutchinson.

What became of the Fort Adams site? Entergy spokesperson Diane Park says that the 2,000- acre (809- hectare) parcel there was sold earlier this year, but could not disclose the purchaser.

Hutchinson says the portfolio of existing sites makes up the vast majority of locations for the various new plant proposals before the NRC,

helped by the infrastructure of switchyards and transmission lines that’s grown up around those sites. “That’s somewhat of a cost advantage,” he says.

Why should utilities look to nuclear? Look no further than the experience of Florida Power & Light Co. (FPL) over the past two years. After being counseled by the Florida Public Service Commission in 2006 to consider coal over natural gas because of the latter’s high prices and susceptibility to supply concerns, FPL in early June saw those same regulators reject a new $6- billion coal- fired plant that the utility had proposed to build in Glades County.

There are 150 coal- fired plants currently proposed across the U.S. The strike- down in Florida may reverberate through all of them, not only because of coal’s limited supply but because nearly everyone expects further carbon- emissions regulations to be handed down within the next decade.

The answer, to some, is simple: “clean,” carbon- free, low- cost nuclear energy, backed by several decades of safe plant operations. In 2004, U.S. nuclear plants generated an all- time high of 788 billion kilowatt- hours (kwh), running at over 90 percent capacity.

“The driver for new nuclear is carbon,” says Bill Griffith, vice president of nuclear operations for Shaw Group’s nuclear power subsidiary Stone & Webster. “The cost of electricity determines to a large extent the type of economy you can manage,” Griffith says. “You saw the blackout in the Northeast a few years ago, but the nuclear plants were right there for them. It was the fossil side of the grid that really had the stability problems. The real driver is more and more of the states want the growth, but they want clean growth. California is even starting to talk about new nuclear for the first time.”

In early April, the Limestone County Economic Development Association announced Alabama’s first certified megasite – a 2,010- acre (814- hectare) industrial site on I- 65 near Athens in northern Alabama. That’s right next door to Browns Ferry. Alabama Gov. Bob Riley, coming off the biggest economic development success of his tenure with the attraction of the ThyssenKrupp steel complex (see p. 488), thinks nuclear is in a good place in a long race.

“TVA is looking at a partially completed Bellefonte plant in northern Alabama, and we have Browns Ferry coming back online,” he says of his state’s nuclear power outlook. “I think you’ll see more people looking at it as an option. Going forward the next 30 years, with their safety record, people are becoming more and more comfortable with them.”

Some territories are so comfortable they’re offering nuclear plant projects the kind of incentive packages usually reserved for the industrial end users such plants would serve. In these pages last year, a spokesman for Entergy Corp. and the NuStart consortium spoke of offers ranging between $800 million and $1 billion.

Asked if he’s ever encountered such offers, Gov. Riley says, “Browns Ferry did not ask for any incentives, no one has asked for any at the Bellefonte plant and there have never been any I know of at the Alabama Power plant.

Going forward, these are huge projects, but there has been no attempt in Alabama by any of those to ask for incentives.”

Beth Thomas, spokesperson for Birmingham- based Southern Nuclear, says, “There are incentives being offered” though it’s not something the company has actively sought in Georgia, where a possible addition of two units at Plant Vogtle is under consideration.

Entergy’s Hutchinson says a lot of states are looking at things like property tax exemptions and infrastructure improvements.

“Louisiana and Mississippi both are looking at incentives,” he says. “They will be somewhat hesitant to lay out on the table what they intend to do until they know with more certainty than today that a plant is going to be built.” While he views those potential packages as important, “they are not as important as certainty on the front end on how you’re going to recover your costs.

Which makes the recent 3- 2 vote by the Louisiana PSC to allow a utility building a nuclear plant to earn interest on the money it is spending to construct it a big step forward.

“Texas has legislation on that issue, Florida has already passed legislation and Duke and Progress Energy are seeking the same things in North Carolina,” says Shaw Group’s Griffith. “Because of the money spent during construction, interest can dilute the profits. And you have to have a long- term recovery mechanism to get the capital out of the plant after it’s built.

The linchpin that could lock in new nuclear investment may come at the federal level, as details of the Energy Act of 2005 related to loan guarantees, production tax credits and risk insurance for the first handful of new plants are just now being finalized by the Dept. of Energy. The act promises these elements to the first 6,000 megawatts of new nuclear generation, with lesser amounts available thereafter. The credits would come over an eight- year period at 1.8 cents per kwh, up to a cap of $125 million annually.

“When you go to Wall Street or a banker to get financing, a federal loan guarantee is worth at least two percentage points on your loan,” says Entergy’s Hutchinson. “That’s a lot of dollars over the years. It’s important to us and to a number of other folks. In fact, that is likely a ‘go’ or ‘no go’ decision for us. If the loan guarantee is not of value when we go to put together project financing, that is probably a deal breaker.”

At the Citi Power, Gas and Utilities conference in June in Charleston, S.C., a panel of CFOs from Duke, Progress and Southern Co. and Michael Kansler, president and CEO of Entergy Operations and chief nuclear officer, pondered possible nuclear growth.

“There are four things we need,” said Kansler. “The loan guarantee program, 100- percent takeoff of the power, the right regulatory framework in the state, and the right construction contract so we know the risk is shared.”

For now, while awaiting construction surety, the utilities are looking at estimated costs of between $1,800 and $2,500 per kilowatt. And the federal incentives are still being worked out even as the utilities face a December 2008 deadline for final COL submittal and look to have plants generating around 2016 or 2017. But all on stage at the Citi conference placed more focus on agreements at the state level. And Kansler may have put it best when it comes to being the first to navigate the shoals of building a new unit in a new era:

“We’re all kind of racing to be second,” he said.

“I don’t think the guarantees are going to be a maker or breaker,” says Shaw’s Griffith. “The financial piece, $18 per megawatt, that’s the real issue.”

The nuclear portion of TVA’s total generation- assets portfolio is among the largest in the nation, at 21 percent.

“If you look at total gigawatt- hours generated from our fleet alone, it would be about 30 percent nuclear,” says TVA spokesman Frank Rapley.

“Up- front capital is over half the cost,” says Jack A. Bailey, vice president, nuclear generation development for TVA Nuclear. “But production costs are the second lowest of any source of generation over a large scale, hydro being the lowest. The high cost argument ignores the fact that as you go into the future, [nuclear is] definitely the cheapest source of generation. It lowered our average cost of production when we brought on Browns Ferry. The busbar cost is 2.7 cents per kilowatt- hour, averaged in to our average of 4.5 cents, which brought our average costs down.”

Bailey points out the economic development ballast of the nuclear plant projects themselves, both during and after construction.

“These are some of the best paying jobs and highest intensity of work projects you could have,” he says. “We employed 2,000 to 2,500 workers during the completion of Browns Ferry. Now we have 160 new, relatively high- paying jobs at the plant. We have the refueling outages every two years that bring in 500 to 600 workers for 45 days at a time. On the materials supply side, smaller commodities tend to be from the region.”

Southern Company’s Plant Vogtle has a similar impact: around 900 permanent employees, after a 1970s construction process that involved some 14,000 people. The plant’s $28 million a year in taxes comprise 74 percent of Burke County’s tax base.

Bailey sees the opportunity for cluster development around the sector, not dissimilar from what the Gulf Coast states have accomplished in oilfield services.

“Why not make the Tennessee Valley a place for that?” he asks, mentioning such niches as engineering and construction services, valve manufacturing, refurbishment and maintenance, refueling services, and inspections and quality assurance firms. “Those are good jobs, and would be useful from an economic development point of view,” he says.

Southern Co. spokespeople say their company knows it’s in a battle for talent as the comeback commences, beginning with the NRC itself, which has hired some 200 engineeers in the past year and a half. Beth Thomas says nuclear engineering programs at such schools as Georgia Tech, North Carolina State and Auburn are ramping up.

“In the late ’60s early ’70s, nuclear engineering was a very hot job market, and it’s returned to that,” says Georgia Power spokesman John Sell. But it’s not just the degreed who may prosper. This industry, like seemingly every other, needs talented welders.

“If anyone can weld stainless as well as carbon steel, they’ll make a lot of money,” says Plant Vogtle spokesman Ellie Daniel. “Electricians, biologists, chemists, they will all be looking to this industry.”

Southern Company’s nuclear fleet comprises six reactors at three sites: the Alvin W. Vogtle plant near Waynesboro, Ga., south of Augusta; the Edwin I Hatch plant new Baxley, Ga.; and the Joseph M. Farley plant near Dothan Ala. Co- owners include Southern subsidiary Georgia Power, Oglethorpe Power Corp., the Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia (MEAG) and, with the smallest percentage, Dalton Utilities.

But that smallest fraction has helped yield some big results, says Dalton Utilities President and CEO Don Cope, who points out that the ability to buy in was brought about in part because of an anti- trust lawsuit the utility brought against Southern in the early 1970s, which resulted in the above- named parties forming the Georgia Integrated Transmission System, allowing for customer- choice, one- time competitive bids on any projects over 900 kilowatts.

“The leadership was very forward- thinking,” Cope says of his company’s

1976 decision to buy into the nuclear plants, along with two fossil- fuel plants. “That partial ownership position has been very beneficial to us financially.”

How beneficial? Cope says Plant Vogtle is “the lowest cost producer of energy of anything we have access to, at less than 2 cents production cost [per kilowatt- hour] at the busbar. The next lowest cost is hydro, and that’s five and a half cents. If we did not have the block of ownership in this very efficient, economically operated plant, our costs to end users would go up significantly.”

The northeast Georgia industrial development picture would certainly be less filled in today without it, he says.

“They realize they have a very good deal when it comes to the cost of electrical energy from Dalton Utilities,” says Cope of his industrial customer base, “and that cost is largely a component of electrical ownership of nuclear facilities. We try to give them the advantage of that low- cost component of our stack.” /

Would he be interested in buying into new nuclear capacity?

“We would hope to have an even higher ownership stake if there is an opportunity and the price is right,” he says. “There are a lot of issues associated with the price to construct new plants, and we are actively engaged.”

So are all the owners of Southern Co.’s nuclear plant assets, as they confront unprecedented population growth and the power demand that comes with it. South of Augusta, Ga., near the bird dog capital of Waynesboro, Plant Vogtle may be one piece of the solution.

Its original two units, color- coded in beige and blue and constructed at a cost of $8.87 billion beginning in 1972, kick out 1,215 megawatts apiece, at a cost that the Nuclear Energy Institute pegged as the fifth- lowest in the nation, at 1.33 cents/kwh. The thickness of the containment dome concrete (4.5 ft.) is mirrored by the thicket of security and safety measures in place at the plant, where redundancy is golden.

Though the 30- story cooling towers dominate the landscape for miles as one approaches the 3,150- acre (1,275- hectare) site, most of the plant is underground. Its power is felt for hundreds of miles via the switchyard just outside the turbine building, starting with nearby large industrial complexes operated by Georgia Power customers International Paper, Procter & Gamble and Augusta Newsprint. Plant spokesman Ellie Daniel says a group of industrial customers was recently convened at the plant.

“We just had the industrial sales managers in this very room to hear about the possible new generation,” he says. “They’re concerned about price, about how we generate it, how we’re becoming more reliable and more efficient.”

A few hundred yards away from the Vogtle units, adjacent to where the company had once built two concrete plants and even an ice plant to help the concrete set, orange cones in the middle of a gravel road mark the diameters of units 3 and 4, now being mulled by Southern Nuclear. The decision to go forward will be based in large part on a cost estimate expected some time in fall 2007 from Westinghouse/Toshiba, the developer of the chosen AP1000 technology that would be employed. The modular AP1000 technology is the only technology design certified by the NRC.

Georgia Power’s John Sell says the importance of that Westinghouse/Toshiba number is rivaled by how that cost will be recovered. He points out that Vogtle’s price went up dramatically in part because off interest cost and in part because of timing, as the Three Mile Island incident spurred major change orders.

Sell says the Georgia PSC has given Georgia Power an accounting order “that will allow us to put in escrow the $51 million for the COL.” The company has put further focus on Vogtle by pulling out of its partial 500- megawatt ownership in the William States Lee III nuclear power project in Cherokee County, S.C., being pursued by Duke Energy, and selling that share to Duke./

Duke is also looking at building a reactor at its abandoned Cherokee site in Gaffney, S.C., whose containment building is best known as the location of the 7.5- million- gallon underwater set for the film The Abyss. That set is still intact on the site, which may now return to its originally intended use some 30 years later.

Another Carolinas- based utility, Progress Energy, this spring chose to delay its timeline for nuclear expansion at the Harris site near New Hill, N.C., focusing instead on conservation and efficiency measures. Duke has also launched such a program, but has not pulled back on its nuclear plans.

However, Progress is moving forward on its plans for two new reactors at the company’s combined Crystal River steam and nuclear power complex in Citrus County, Fla.

In fact, said Progress CFO Peter Scott at the Citi conference in June, the company has hopes it will be able to migrate the construction work force for the project from among the 1,000 or so workers currently on a non- nuclear project literally just down the road.

Back in Georgia, if the numbers fall in place, public approval will probably be waiting for them. Daniel, whose father helped design the Savannah River Site across the river in South Carolina and who himself was on Vogtle’s construction team, says the surrounding communities have always had a pro- nuclear, positive relationship with the company.

“At the public meetings, most of the objections come from people who don’t live here,” adds Sell. “People here are asking, ‘How fast we can build? How can we expedite it? Who do we have to call?'”

Southern Co. subsidiary Alabama Power was one of the key players in attracting the $3.7- billion ThyssenKrupp steel plant to the Mobile area, where it will take advantage of rates ameliorated by nuclear power. Ironically, it’s a shortage of specialized steel forgings, combined with the market- driving effects of China on both steel and power demand, that is presenting one of the major roadblocks to the U.S. nuclear power comeback.

Though BWXT is ramping up plants in Ohio and Indiana to serve the market, “there are currently no foundries in the U.S. capable of producing reactor pressure vessel ultra- forgings,” says Entergy’s Hutchinson. In fact, only one foundry in the world, Japan Steel Works, has the capability for making the ingots, and its capacity is currently at 7.3 reactor vessels per year, given that the company also serves a larger universe of industrial concerns that includes the petrochemical industry and other processing sectors.

“There is a minimum of a four- year lead time today for forgings out of Japan Steel Works,” says Hutchinson. “All of us are in the process of evaluating the long lead time requirements for forgings, and trying to get some kind of forging reservations in place.”

TVA’s Jack Bailey says Korean steel companies are moving in the direction of offering this capability. But even with just the 30 or so nuclear plants identified as wanting to build by 2020, there would be some delivery constraints.

“I’m hearing the first five or six, no problem,” he says. “You have to order a year earlier than you normally would, but you should be able to meet the schedule. At some point, as more people get in line, you’ll meet the point of constraint. TVA is looking at 2016 or 2017 for Bellefonte, and right now we could still get in line and meet the requirements. We’re seeing increase in demand in China, Russia, India, European countries. So the question is how quickly those new plants can be built. The infrastructure to support the nuclear industry will come back, but it is a worldwide market.”

“The world has the capacity to make about 450 major large forgings a year,” says Shaw Group’s Griffith. “If you want to talk about economic growth for the U.S., it’s going to be those guys like BWXT, who get the material and have capacity to do something with it.”

Site Selection Online – The magazine of Corporate Real Estate Strategy and Area Economic Development.

©2007 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.