n December 22, 2004, Dell Inc. and North Carolina officials were gathering at a

podium in Winston-Salem to announce the company’s investment of more than $100

million in a new assembly plant. State transportation workers at that moment were on the

ground at Alliance Science and Technology Park staking rights-of-way for the project, in

preparation for the grading contractor one week later. The site was finished and graded

by the end of January.

But state and local officials had staked out the territory long before.

“The site was put together three years ago to provide a location for spin-off technology

business from our research park downtown,” says Bob Leak, Jr., president of Winston-

Salem Business Inc. “Because that site had been assembled, zoned and permitted, we

were able to put it on the table for Dell to consider.”

Now the spin-off is of an entirely different caliber, all because of an unprecedented blend

of teamwork and hard work. The project may have been code-named Merlin, but the

magic took more than waving a wand.

Five years ago in these pages, Dell Corp.’s Kip Thompson, vice president, global

facilities, said, “We have a mantra in Dell corporate real estate: Set unrealistic

expectations … and then exceed them.” He also said, “`No’ simply means that you don’t

yet have enough information.”

|

| Jordy Whichard III |

The context of those comments was the internal workings of Dell’s then-12-person

corporate real estate department, on the heels of a big project in Nashville. But the nature

of expectations and the primacy of information were also at the heart of the company’s

unfolding project in Winston-Salem.

In response to a lawsuit by the N.C. Press Association, 4,000 pages of documents relating

the intimate details of the deal’s negotiations were released in early 2005. According to

published accounts of the notes, the frank bargaining between Thompson and state

officials included references to patriotism, gratitude for 2,000 new jobs and threats to

take the project to Tennessee or elsewhere.

In fact, Dell recently made the decision to purchase only 14 of its optioned 326 acres

[132 hectares] in Nashville, releasing the balance back to the airport authority. But

Thompson says there is no correlation in the timing: “We still have the ability to expand

and have continued to expand in Tennessee.”

The negotiation details have sparked further conversation in the state about incentives’

worthiness and confidentiality. But that has done nothing to derail the confidence all

parties have in the project and its potential, as Dell seeks to better serve the Eastern

seaboard corporate and institutional client base that makes up some 85 percent of its

business.

“It’s good growth for the country, for the state of North Carolina, for the Triad as well as

for the Winston-Salem community,” Thompson tells Site Selection from the company’s

Round Rock, Texas, headquarters. “It’s also a good thing for Dell. Frankly, I think it’s a

great day for manufacturing in the United States.”

Thompson says one of the reasons Dell can continue to manufacture in the United States

is its commitment to making productivity, quality and customer experience

improvements.

“Here we have an opportunity with a new facility to capture everything we’ve learned,”

he says. “Instead of incremental improvements, we’re able to capture all the

improvements from the past couple years — inbound logistics, quality measures, time to

put the products together, outbound logistics improvements — and wrap them all into

one.”

That’s what state officials did too, with Commerce Sec. Jim Fain doing the bulk of

negotiating, Gov. Mike Easley meeting with Dell officials in July 2004 and a special

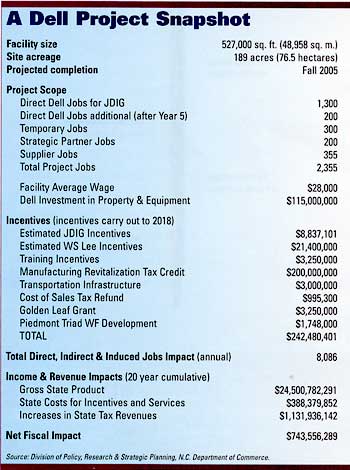

legislative session in November 2004 approving $242 million in tax breaks and other

incentives — a 40-percent jump up from the $166 million the company garnered for its

Nashville plant. Many in North Carolina wanted the process to be more open, but others

were concerned that could potentially blow the entire deal, at a time when the state —

and the Triad region especially — could use a big-jobs project in the wake of textile,

tobacco and other industry cutbacks.

Planted firmly in the middle of the ensuing debate is Jordy Whichard III, appointed by

Gov. Easley as chairman of the North Carolina Economic Development Board, an

advisory body. He’s also the fourth generation in his family to be in the newspaper

business, serving as group publisher of Cox North Carolina Publications, Inc., and

publisher of The Daily Reflector in Greenville, N.C. Whichard is a director of the North

Carolina Citizens for Business and Industry (NCCBI) as well as the N.C. Press

Foundation. He is trying to forge a third role in the ongoing incentives and disclosure

debate — a discussion that is also in full bloom in Georgia, Virginia and other states.

“Dell had a clear understanding of what it needed to do, and they came to the table in a

professional but determined way to put on the table what they thought could make North

Carolina the successful location in what was a highly competitive situation,” he says,

calling the negotiations professional, frank, “but in good faith.”

As for the larger question, says Whichard, “In the ideal world, full access and openness is

an ideal that should be pursued. In the real world of competition, whether for an industry

recruitment or a CEO for a university, that full transparency too early in the game can put

the entity at a competitive disadvantage.”

Where to tread that thin line is the subject of proposed legislation to change the state’s

open government statutes. Whichard is trying to facilitate discussions between NCCBI

and the press association, and hopes to help all parties reach a compromise solution by

year’s end. Central to that discussion are questions like “What is a trade secret?” and

“When is a project considered `announced’?”

Asked at what exact point he thinks details of business attraction negotiations should be

made public, Dell’s Kip Thompson says, “It depends on the community. Clearly there is

a need for information to flow, that does not compromise companies being able to do

their business. There is a need for the public sector to have information available as well.

What that point is would be, in the abstract, a hard line to draw.”

It’s easy to let the incentives discussion overshadow other positive developments for

corporate investment, like the $700-million transportation im-provement bill and the

freezing of the unemployment tax rate (both passed in 2003), or the continuing rank of

the state among the lowest in unionization. But Whichard and others see training among

the best advantages the Tarheel State has to offer.

“We were the first state in 1958 to offer technical training in community colleges,” he

says. “Every legislative biennium there is full funding throughout the education system.

Gov. Easley has done that again this budget cycle. Look at RTP [Research Triangle Park

in Raleigh-Durham] and you can see it’s the most important non-cash incentive that the

state offers.”

That sentiment is widespread. At a Carolinas Competitiveness Forum hosted by Duke

Power in 2004, when the 300 participants were asked what asset the Carolinas should

enhance to be even more competitive, more than 33 percent answered “education and

training,” while another 19 percent said “work-force development.” Coincidentally, last

fall, a new $3-million training grant program was launched by Duke Power and the

state’s community colleges, highlighting Forsyth Tech in Winston-Salem among them.

(Duke Power will be the Dell facility’s primary provider.)

Final training details are still being worked out between Dell and the community college

system in the Triad. Even though Dell prefers to bring training in-house for the most part,

this type of development is on the radar. Thompson extolls the state’s respect for skills

development.

“We want to be in an environment where people are accustomed to improving their

capabilities,” he says. “What we found in North Carolina is a community that is

committed to education and committed to the ongoing development of its people.”

Taxation infrastructure was in the Triad’s favor as well. According to a January 2005

report on county government costs and tax burdens in North Carolina issued by the

Raleigh-based John Locke Foundation’s Center for Local Innovation, the combined tax

and fee burden of the county Dell has chosen and its eight municipalities ranked 38th in

2003, down from 33rd in 2002. That’s the kind of trend a corporation can accommodate.

|

| Bob Leak, Jr., president, Winston-Salem Business Inc. |

Peter Kaharl, Dell’s senior manager, corporate real estate and construction, came into the

picture after the Triad region had been chosen. He says RFPs were issued to groups in

High Point, Winston-Salem, Davidson County and Greensboro detailing Dell’s

requirements and timeline. A total of six sites were submitted, as well as potential utility

cost reductions and traffic improvements. Thompson says continuity and redundancy of

power were the key utility requirements.

But transportation issues lingered as the leading issue as negotiations progressed.

Davidson Co. was dropped from the list because of projected employee travel time.

While many think the forthcoming 2009 opening of the FedEx hub in Greensboro

certainly played a factor, Dell’s transport concerns were a bit more immediate.

“Trying to get people to understand what Dell’s requirements are is difficult because of

magnitude,” says Kaharl. “It’s hard to get people to understand that when we want a four-

lane roadway that has the capability to enter and exit from both directions.”

“It came down to [whether we could] fix some roads that were small two-lane country

roads and turn them into three- or four-lane highways, and do it in a timely fashion,” says

Leak. “There was a lot of discussion with the North Carolina Board of Transportation —

local board member Nancy Dunn was very active, along with Pat Ivey, a division

engineer with the district office. They rolled up their sleeves, determined what road could

be improved immediately, made some inquiries of the state, and ultimately were able to

commit to improvements that I think really helped cement the deal for us.”

Thompson says since customer experience drives everything at Dell — and since time to

market is so crucial to that experience — the logistics infrastructure side of Site Selection

is primary in his team’s sights, going all the way to the custom product configurations

that have helped define Dell.

“When a customer places an order, we give them what they want in the time frame they

want it,” he says.

North Carolina officials couldn’t — and wouldn’t — have said it better.

The Dell-related spin-off is happening nearly as fast as the project itself. Leak says that

spin-off, observed first-hand in Round Rock, was a prime motivation for his team’s hard

work.

“Within about nine days of Dell’s announcement, we put over 100 acres [40.5 hectares]

of real estate under contract about 3 miles [4.8 km.] away, where we haven’t sold

anything in three years,” he says. By July, Leak expects to have close to 1 million sq. ft.

(92,900 sq. m.) under contract. He says there is one good reason:

“We have arrived because we have a team approach to economic development that

involves the public and private sector. To me, that’s the legacy of the Dell project — the

team that was created in the community and the state to go do these kinds of projects.”