No sector now is more active than logistics, and there is no busier niche within it than cold chain for grocery and medical needs. The busiest companies within that niche, before and since COVID-19, are automated logistics pioneers and the grocers they serve.

Digital Commerce 360’s 2020 Online Food Report, released in August, analyzes the top 1,000 food-dedicated retailers, as well as mass merchants with growing sales in the category — Walmart and Amazon represent more than 60% of the online grocery market, with Walmart having the biggest market share of online food in 2019 at 31%.

According to the report, even before the pandemic struck, online sales by grocery retailers had grown by 30.7% in 2019 — the fastest-growing sales channel for a U.S. grocery market that reached $1.25 trillion in overall sales last year. A survey by FMI — The Food Industry Association — found that online purchases as a percent of all grocery spending grew from 10.5% in 2019 to nearly 28% in March/April 2020. Nearly 85% of online shoppers surveyed in May 2020 cited concern about contracting the virus. A separate survey by EY in May 2020 reveals that 44% of respondents expect to do more grocery shopping online. A rundown by retailer:

Albertsons: For the eight weeks ending April 25, e-commerce sales grew by 243% over the same period in 2019 — including a 374% year-over-year increase in April.

Amazon: Online sales of groceries tripled during Q2 2020, and Amazon increased its grocery delivery capacity by 160%. The Digital Commerce 360 research indicates Amazon this summer was hiring for dozens of grocery-related positions, not just at its first non-Whole Foods grocery store in Los Angeles, but for other grocery-driven positions in such markets as Washington, D.C.; Seattle; Austin; and the Chicago suburb of Schaumburg, Illinois. The company now has opened 26 Amazon Go convenience stores and its first Go Grocery store, in Seattle near Amazon’s HQ.

Walmart: Online grocery sales reached nearly $900 million in March 2020, up 99% from March 2019.

Costco: For the fiscal quarter ended May 10, 2020, online sales were up 64.5% year over year, driven by what CFO Richard Galanti called “an incredible” rate of online grocery sales which, if it counted sales made via app-based delivery service Instacart, “would have been slightly over 100%.”

Kroger: Online sales were up 92% year-over-year for the quarter ended May 23, 2020, with sales growth registering in the triple digits. In the eight weeks ending in mid-May, the company hired 100,000 people, including e-commerce and distribution workers.

Among the online retailers Digital Commerce 360 talked to was Drinks.com, whose CEO Zac Brandenberg said the company was scaling up operations, which meant “ensuring that our winery partners can scale their own production operations up to meet our growing needs and increasing warehouse staffing and resources.” The company provides e-commerce technology for Kroger and others, and is the parent company for online retailers Wine Insider and Martha Stewart Wine Co. From March 25 through mid-April, orders at those two sites increased by 250% to 300% compared to usual volume for that time of year.

And yes, all that home baking has driven its share of online grocery e-commerce, too: King Arthur Baking Co., maker of the eponymous flour, reported in March that online sales were up by 1,000% over February, and its online all-purpose and bread flour sales were up by 2,000% to 3,000% year over year.

Cold Is Hot

How do such spikes affect logistics? According to company reports, recent pandemic hiring spurts at Albertsons, Amazon, Kroger, Target and Walmart totaled 640,000 overall, with a good chunk of those jobs in fulfillment as well as stores. Online grocer Thrive Market added 150 employees to its fulfillment operation. Driven in part by grocery, Target added 80,000 workers at the Shipt same-day delivery business it acquired in 2017.

Sometimes there is a trade-off: As grocery giant Ahold Delhaize continues to grow a new network of fulfillment centers for its many store brands including Hannaford, Food Lion and Giant Food, its Chicago-based online grocery division Peapod stopped deliveries in the Midwest and announced plans to close four distribution and food-prep facilities that employed 500 altogether. Meanwhile, Ahold’s East Coast network for its distribution network continues to grow, with a new Giant Food fulfillment center expansion in Jessup, Maryland; and two new fully automated frozen warehouses that Americold will build for the company under 20-year agreements in Plainville, Connecticut, and Mountville, Pennsylvania. Those two facilities will expand cold-storage space by 24 million cubic feet in 500,000 sq. ft. (46,450 sq. m.) of warehouse space with 59,000 pallet positions. Each will employ 200 people.

Chris Lewis, executive vice president, supply chain for retail business services at Ahold Delhaize USA, said the new facilities offer the opportunity to innovate in new frozen storage warehouse design “to support the next generation of grocery retail,” including transforming facilities to enhance automation and leverage technology advancements, such as an integrated transportation management system and end-to-end forecasting and replenishment technology. The company’s fleet of 1,000 trucks travels more than 120 million miles (193 million km.) annually and delivers 1.1 billion cases to stores.

“Through this expansion,” said Lewis, “we will continue to modernize our supply chain distribution, transportation and procurement through a fully integrated, self-distribution model that will be managed by our companies directly and locally.”

The company — whose brands altogether comprise nearly 2,000 retail stores and more than 6 million annualized online grocery orders — anticipates its current distribution center network will grow from the current 16 facilities to 23 by 2023.

From Micro-Fulfillment to Meal Kits

One thing is becoming clear across the whole sector: With such innovations as curbside pickup, home delivery and in-store fulfillment, the lines between warehouse, store and home are blurred like never before.

According to Digital Commerce 360, Albertsons is pursuing automated fulfillment in the form of “micro-fulfillment centers” inside stores, using technology from Massachusetts-based robotics firm Takeoff Technologies. The first one opened last fall at a Safeway in San Francisco. As a Boston Globe profile of the company said in its headline, “This automated supermarket can bag 60 items in five minutes.” The firm has grown to more than 100 employees less than four years since its founding by José Vicente Aguerrevere and Max Pedró, two Harvard Business School graduates. Aguerrevere was recognized as social entrepreneur of the year by the World Economic Forum’s Schwab Foundation.

Another new shape for grocery is meal kits, led by such firms as Blue Apron, HelloFresh and Sun Basket. Blue Apron saw Q2 2020 revenues increase by 29% over Q1, and took action to increase its fulfillment center capacity, headcount and employee wages. In Q2 2020, Berlin-based HelloFresh, which operates in 14 countries, delivered 149 million meals and reached 4.18 million active customers worldwide, with a 103% increase in orders and 123% increase in year-over-year revenue. The company recently expanded to Sweden and Denmark (where it operates a headquarters in Copenhagen), and in its August earnings report announced it has signed lease agreements for two new production sites in Nuneaton, located in Warwickshire just east of Birmingham in the UK; and in Newnan, Georgia, southwest of Atlanta. “Both new sites are crucial to the company’s growth plans and will generate approximately 1,400 jobs,” the company said.

Ocado and El Mercado

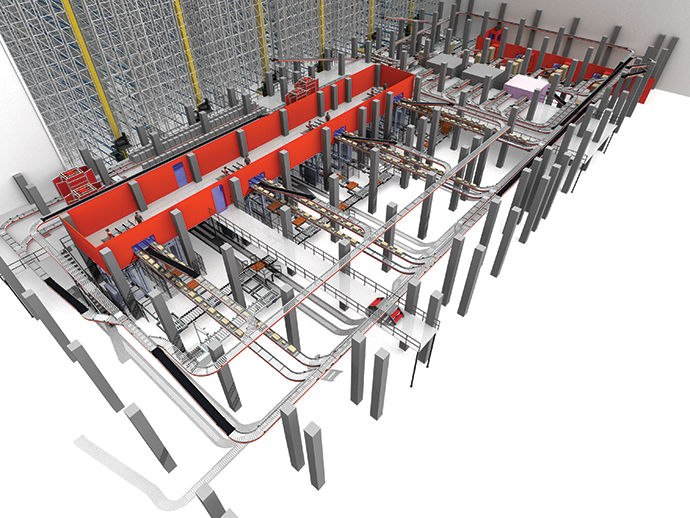

The Kroger Co. and Ocado, the London-based grocery e-commerce technology firm, recently announced Frederick, Maryland, as the latest location for a Customer Fulfillment Center (CFC). The project will create 400 jobs and attract $55 million in investment. Up to 100 more jobs will be added later as the service area of the 350,000-sq.-ft. (32,515-sq.-m.) facility expands. Serving Maryland, Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia, “the warehouse will be a key component of the seamless fulfilment ecosystem that Kroger is developing for customers across the United States,” said Luke Jensen, CEO of Ocado Solutions.

The two companies in June announced the continued expansion of their partnership with plans to construct three new CFCs in the Great Lakes, Pacific Northwest and West regions that collectively will generate more than 1,000 new jobs. Exact locations were still not specified as of late August. “Through our strategic partnership, we are engineering a model for these regions, leveraging advanced robotics technology and creative solutions to redefine the customer experience,” said Robert Clark, Kroger’s senior vice president of supply chain, manufacturing and sourcing.

The newly named locations will complement the retailer’s previously announced CFC sites in Frederick; Monroe, Ohio; Groveland, Florida; Atlanta, Georgia (Forest Park, near the airport); Dallas, Texas (Lancaster); and Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin. The Florida site near Orlando will be a $125 million e-commerce warehouse. Kroger plans to open the country’s first CFC in Monroe, Ohio, a suburb of its hometown of Cincinnati, in early 2021. The ultimate plan is to roll out a total of 20 CFCs for Kroger in the coming years.

The three new sites will be smaller, ranging from 300,000 sq. ft. to 150,000 sq. ft. (27,870 to 13,935 sq. m.). “Alongside the scale and wider benefits of larger CFCs, smaller format and mini CFCs will allow Kroger to reach more geographies with Ocado’s automation, while also catering to a wide range of options for delivery,” said Ocado’s Luke Jensen.

Kroger is Ocado’s most high-profile client, but certainly not its only one. In March, the company announced its first international operations were live for a CFC in Fleury-Mérogis, near Paris, for Groupe Casino and its Monoprix brand. Meanwhile, the first CFC in North America was not in the U.S., but in Canada, where Ocado in April announced the launch of a new site for Empire’s new online grocery home delivery service, Voilà by Sobeys, in Vaughan, Ontario, in Greater Toronto. Other CFC sites for Sobeys are in the works in Pointe-Claire in Greater Montreal, and near Ottawa.

Meanwhile the automation innovator is pursuing a vertical farming JV with Cincinnati-based 80 Acres Farms and Netherlands-based Priva Holding called Infinite Acres, and it has acquired a majority stake in Jones Food Co., Europe’s largest operating vertical farm, based in Scunthorpe, UK. The ultimate goal is placing vertical farms within or next to CFCs. All such growth is backed by development centers where, as of spring 2019, more than 1,400 technologists were hard at work on AI, IoT and robotics solutions in locations in in Hatfield (UK), Sofia (Bulgaria), Wroclaw and Krakow (Poland), and Barcelona (Spain). A sixth center opened in London last summer, where an initial cohort of 40 employees is expected to grow to 300.

The TGW Point of View

One material handling technology firm with its hands in a lot of automated facilities is Austria-based TGW Logistics Group. Among its 3,700 employees worldwide is Andy Lockhart, vice president of business development, based in Grand Rapids, Michigan. When asked how much the technology is influencing facility location and design by customers today, he said it depends on what point in the process the engagement has begun. If the user and automation firm work together early in the planning stages, then the design can be higher and have the right column spacing for automation equipment. “If a spec building is already built,” he says, “you tend to lose more space in the inner storage areas.”

Indeed, height and automation go together. “We can build very tall buildings,” Lockhart says, especially in Europe, where garment maker engelbert strauss, operates in a 150-ft. (nearly 47-m.) building in the German state of Hesse where TGW systems include shuttles more than six stories tall. The system allows shipping capacity to be tripled.

“The average warehouse is 36 feet,” Lockhart explains. “If you can go to 40 or 45 feet, you can get a lot more out of the automation.” With freezer warehouses, he says, heat escapes to the roof, so the smaller the footprint, the better, and again, “automation can help because you can go high.” One customer, the largest grocer in Switzerland, has a building more than 10 stories tall with half below ground and half above.

He says the flurry of grocery warehouse activity — “which is getting slightly mad” — is all about getting the dock closer to the customer. “Going into urban areas, you’ll see more multistory, because as you get closer into cities, the costs go through the roof, and the smaller footprint becomes more of an advantage.” He expects to see more of that everywhere, because “it’s cheaper to go up than go wide.” Total cost of ownership analysis TGW typically performs also takes into account less labor and therefore less parking, meaning a smaller piece of land and therefore less property tax.

The trick is to manage the combination of large online grocery orders, different chill levels (frozen, chilled, ambient, etc.) and that all important last mile. “That’s the expensive piece,” Lockhart says. Bananas alone need their own ripening rooms at large grocer warehouses, he says. And ice cream has to be kept colder than other frozen items. “When you look at the mix of a grocery basket in Europe versus the U.S., the freezer element is bigger in the U.S.,” he says. That means a big expense for frozen storage, but at the same time, the economics for automation are actually better, because more of that basket is frozen.

That said, says the native Englishman, “Grocery here is so far behind Europe. I moved to the U.S. in 2004, and we had click-and-collect and Instacart delivery before I left England. It’s only getting going here in the last few years. Now in the UK, they are so far ahead of us in automated grocery fulfillment. But with COVID-19 now, the micro-fulfillment concept of putting automation close to the customer is getting a lot of interest. Do you want to take out part of the space in a store and put in automation, or do a stand-alone building? All of this is something grocers are now looking at. The world knows that the Amazon distribution center is going out of fashion. It’s only a matter of time.”

Cold Chain Innovation

What’s next? New ideas are afoot in different corners of the world, but as Lockhart suggests, the UK is at the forefront.

A new African Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Cooling and Cold Chain based in Rwanda will help get farmers’ produce to market quickly and efficiently — reducing food waste, boosting profits and creating jobs. Based in Kigali and inspired by the University of Rwanda’s existing Africa Centre of Excellence in Energy for Sustainable Development, the new center aims to link the country’s farmers, logistics providers and agri-food businesses with a range of experts and investors. In future phases, the scope will be expanded to cover interested partners in Africa.

Rwanda’s Cooling Initiative (RCOOL) provides the foundation for the new center, which is part of the country’s National Cooling Strategy, launched in 2019. Researchers from the University of Birmingham and Edinburgh’s Heriot Watt University are joining RCOOL to apply their expertise with rural cooling that can be used for food and medicines.

“The African Centre of Excellence in Energy for Sustainable Development is delighted to be part of this important work on sustainable cold chain for food and medicines — energy-efficient, climate-friendly, and affordable cooling and cold chains can improve agricultural efficiency and boost farmers’ incomes, driving real environmental and economic change,” said Professor Etienne Ntagwirumugara, director of the organization.

More innovation is coming from a new partnership announced in July between Hyundai Air Mobility and London-based Urban-Air Port Ltd. Hyundai plans to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years in urban air mobility: urban transportation systems to move people and cargo by air. Hyundai forecasts the air mobility market will be worth nearly $1.5T over the next 20 years.

The Urban-Air Port (UAP) design has a 60% smaller footprint than a traditional heliport or nearest-state-of-the-art ‘vertiports,’ allowing for quick and easy installation in space-limited urban sites and providing both passenger/cargo processing/amenities and vehicle charging/maintenance facilities within its ultra-compact form. Two UK cities (one still unnamed) have already signed on to support development in 2021, including Coventry in the West Midlands, which will host UK City of Culture 2021 and the Commonwealth Games.

Urban-Air Port Chief Development Officer Adrian Zanelli tells Site Selection the Coventry connection came about through ties with the University of Coventry. Who else is interested? “We are currently speaking to cities across Europe, APAC, China and the Americas,” he says, in addition to promoting their floating product for coastal regions. Asked how the concept could work with cold chain, he says, “Advanced air mobility systems will bring the speed so necessary to cold chain logistics,” especially where things typically slow down in urban areas. “With our infrastructure, logistics operators can set up mini UAP fulfillment centers in and around cities and have larger aircraft bring in larger loads, making the operation far more efficient.”

Zanelli says urban air mobility will allow logistics facilities to be far more automated, distributed and scalable. “The shorter ranges of electric aircraft and the lower noise, plus the need to reduce delivery times by keeping off roads, will see logistics hubs being further distributed throughout cities,” he says. “Remote operation and automation will drive this trend as well. This reduces the overall delivery times even further. To be located more widely across cities, logistics facilities will have to become smaller.

“Roads, ships, airports and rail aren’t going anywhere suddenly, however,” he says. “If this pandemic shows us anything, it’s that flexibility and adaptability are key, and advanced air mobility plus innovative, intelligent ground infrastructure like the Urban-Air Port provides that, to work in concert with existing transport infrastructure. We are in talks with airport-based and port-based logistics service providers and with grocery delivery providers here in the UK.”