The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed the vulnerabilities of the United States’ reliance on imported medical supplies and equipment. Global manufacturers of these much-needed products have had capacities curtailed due to shutdowns, social distancing, and travel restrictions. At the same time more than 50 countries around the world have embargoed or restricted exports of items like personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators and other much-needed medical equipment and pharmaceutical products.

COVID-19 is suffocating the global medical supplies and equipment supply chain. Supply disruption, increasing regulatory controls and a heightened demand have led to critical shortages of PPE and medical equipment in the U.S. and around the world. This disruption could not have come at a worse time, as the COVID-19 viral curve continues its exponential trajectory and demand for PPE and medical equipment is peaking globally.

In the near term, companies are ramping up round-the-clock production wherever possible and in some cases rapidly reconfiguring U.S. plants to make these products closer to home. In parallel, multinational C-suite leaders are being forced to quickly evaluate supply chain risks.

In the longer term, the growing national chorus for defending the strategic importance of medical products and equipment will lead many companies to reconsider their global manufacturing footprints and future investment locations. Policies being developed in the executive and legislative branches are seeking to make the U.S. the destination for those new investments. And Robert Atkinson, founder and president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, this week has authored a proposal for a new national industrial strategy to strengthen industries that, as he puts it, “are too critical to fail.”

Too Many Eggs in Too Few Baskets: U.S. Reliance on Globalized Supply Chains

The U.S. is heavily reliant on China for its medical supply chain. Over the past 15 years, U.S. firms have invested over US$800 million into China’s med-tech sector, an amount that nearly equals all investments from U.S. firms in the sector in other locations in the world (omitting their home country) over the same period. Major U.S. companies have developed China- and India-dominated supply chains for the products needed to fight the COVID-19 pandemic such as PPE, ventilators and pharmaceuticals.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) — which includes face shields, protective garments, mouth-nose-protection equipment, gloves, visors and goggles — is a major export of China globally. In 2018, China accounted for 43% of global PPE exports and had a 48% share of the U.S. market. During February, when China imposed travel restrictions and factories were shut down, exports of these products to the U.S. declined by nearly 20%.

However, after its own COVID-19 crisis, China subsidized and quickly ramped up PPE and medical equipment production and is now producing masks, ventilators, and APIs at a breakneck pace and supplying the world with the tools to battle COVID-19.

This response from China clearly demonstrates why companies invested there, the resilience of its manufacturing base, the volumes it can produce, and the importance that China has for global supply chains.

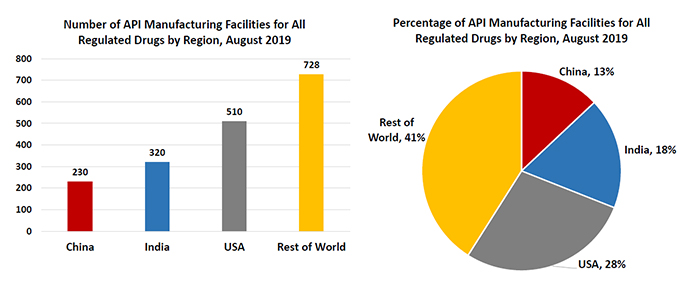

Only 28% of the manufacturing facilities making APIs for the U.S. market are located in the U.S. A staggering 72% are outside the U.S., with 18% in India and 13% in China.

Just as COVID-19 impedes the breathing of those afflicted by it, the virus has also constricted the supply of ventilators globally. Last year the world demand for ventilators totaled 77,000. This month the state of New York alone requested 33,000 units from the U.S. government. States across the U.S. that have been struck hard by COVID-19 are straining an already limited supply.

China supplies the U.S. with 39% of all medical devices, and many key components for ventilators are made in Chinese facilities.

The U.S. reliance on China and India for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is another area of the supply chain under pressure from COVID-19. Between 2010 and 2019, the number of registered facilities manufacturing APIs in China for U.S. pharmaceutical firms more than doubled, according to the FDA. The FDA has also said that only 28% of the manufacturing facilities making APIs for the U.S. market are located in the U.S. A staggering 72% are outside the U.S., with 18% in India and 13% in China.

The FDA does not collect data on the volumes these factories produce, but according to the United States Commerce Department, Chinese firms have captured a disproportionate share of the U.S. market for essential and non-essential medicines including a 97% share of antibiotics, 95% of ibuprofen, and 70% of acetaminophen.

Further stressing the U.S. medical supply chain are the number of pharmaceutical products produced in India. The U.S. annually imports $5 billion worth of drugs from India, which amounts to 40% of total U.S. generic drugs. India relies on Chinese APIs for 70% of its raw materials. As India combats COVID-19, with its own nationwide shutdown, the government has also restricted exports of 26 pharmaceutical ingredients and medicines that include acetaminophen and numerous antibiotics. India’s reliance on Chinese APIs and its own export restrictions are further compounding shocks to the global pharmaceutical supply chain.

Global giants in the pharmaceutical sector are expressing varying levels of caution to investors regarding the potential shortages of products due to supply chain disruption. AstraZeneca, Merck and Pfizer have all said that interruptions caused by the pandemic and export restrictions are likely to affect supply. Netherlands-domiciled Mylan, the second-largest generic and specialty pharmaceutical company in the world, has expressed optimism that its top 25 products, which do not depend on sourcing from China, would not experience disruption.

However, they note that some products could be in short supply if the situation persists for several months. Conversely, Pfizer has told investors that the virus will impact manufacturing and supply chains, despite most of its sourcing occurring outside of China. The mixed messaging reflects the opaqueness of the global pharmaceutical supply chain and the challenge of identifying the pressure points within the companies’ own supply chains.

Incentivizing American Production: Legislative Responses to Supply Shortages

Last month, President Trump enacted the “Defense Production Act” to stem the immediate shortage of supplies by demanding major companies like 3M, General Motors, General Electric, Hanesbrands and others allocate production lines for the manufacturing of key products needed to fight COVID-19. (This demand was made even as some of those companies already were well down the road in doing just that.)

At the same time, Trump is also developing additional executive actions, while Congress is drafting bipartisan legislation. These actions are aimed at developing long-term policies that will incentivize companies to reshore production facilities and provide the FDA with greater tools to monitor strategic supply chain risk.

March 2020 saw two separate bills introduced in the House and Senate that respond to the US reliance on foreign countries for medical supplies. The “Securing America’s Medicine Cabinet Act” sponsored by Senators Robert Menendez (D-New Jersey) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tennessee) aims at increasing U.S.-based manufacturing of APIs by improving advanced manufacturing practices through providing incentives and authorizing US$100 million to develop “Centers of Excellence” to spur innovation. Senator Menendez is targeting his home state of New Jersey, and its robust pharmaceutical sector, as a destination for firms reshoring to the U.S.

At the same time, in the House of Representatives, Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wisconsin) and Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Wisconsin) introduced the “Medical Supply Chain Security Act.” This legislation would provide authority to the FDA to assess the security of U.S. medical product supply chain, including API and medical devices, by requiring manufacturers to disclose the source of origin, use of raw materials, manufacturing capacity and other information deemed relevant. Currently the FDA does not collect this data, which has made it a challenge to assess the volumes of APIs that China supplies to the U.S. and the risk that supply chain disruptions could cause to essential drugs.

President Trump and Peter Navarro, director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing, are also in the process of developing an executive order that would provide long-term incentives for U.S.-based companies to manufacture pharmaceutical products and medical supplies domestically. The proposed legislations and executive actions provide a framework to monitor supply chain security, incentivize companies to manufacture domestically, and foster the advanced manufacturing processes that are needed to make the manufacturing of supplies and equipment cost effective.

A policy that has not been reported, but which could produce the desired effect of reshoring, would be for President Trump to institute another tax cut to repatriate offshore retained earnings, but this time with more strings attached. The 2017 tax policy included cutting the tax rate on repatriated assets from 35% to 15%. This targeted bringing $4 trillion back to the U.S. While it succeeded in bringing back $465 billion, more than $3 trillion remains overseas. Additionally, much of the money that was repatriated went into stock buybacks and did not lead to the reshoring manufacturing boom that was an intended outcome.

Adding more obligations to a new rebate on repatriation, such as requiring the establishment of U.S.-based production facilities, could lead to President Trump’s goal of spurring an “American Manufacturing Renaissance” and stem the tide of the looming unemployment crisis the U.S. currently faces as a result of COVID-19.

While policy options are being developed and seem likely to pass, the pandemic may limit Congress’ ability to pass bills quickly. U.S. multinationals need to find short-term financial gains to offset the losses that are being forecast due to the economic slowdown, and for many China is that market. Drug sales in China totaled $137 billion in 2018, and are projected at 3% to 6% annual growth over the next few years. COVID-19 started in China and it will be the first nation to get back to business. As the world’s second largest economy, China may just be a bright spot for revenue creation as global economies lag during the rest of 2020.

Strategic Location Decisions: Pending Actions

Companies were driven to manufacture and source medical supplies, equipment, devices and pharmaceutical products in China, India and other low-cost countries due to the savings that offshoring provided. The U.S.-China trade war led to the adoption of a China+1 strategy for many multinationals, staying in China to meet domestic demand, but relocating exports to other more competitive global locations, like Vietnam. Medical equipment and pharmaceutical companies just may follow this model after COVID-19 prior to making any moves to reshore in the U.S.

U.S. multinationals need to find short-term financial gains to offset the losses that are being forecast … and for many China is that market. Drug sales in China totaled $137 billion in 2018, and are projected at 3% to 6% annual growth over the next few years.

Post-COVID-19, companies will rigorously assess their supply chain vulnerabilities. The crisis has demonstrated that a reliance on sourcing from two primary geographies poses risks that could lead to financial losses, public shaming and brand degradation. Harnessing ecosystems where companies have a pool of highly trained engineers, top tier R&D, access to advanced manufacturing technology, as well as public and private institutions and universities through “Centers of Excellence,” could be a critical factor to determining the optimal sites for future manufacturing locations.

Top pharmaceutical companies are already messaging the public that they are seeking new locations outside of China and India. Turning this messaging into investment will require that the proposed Federal legislations are enacted quickly. As Federal legislation is passed, U.S. state investment promotion agencies (as well as territories such as biopharma-friendly Puerto Rico) should begin aggressively promoting competitive investment attraction packages to entice these companies to their geographies.

Ultimately, the need to de-risk the supply chain, access to advanced technology, acceptable returns on investment, as well as the incentives that will sweeten the deals, will drive the reshoring of medical product and pharmaceutical manufacturing to the U.S.

Tractus Asia Ltd., (www.tractus-asia.com) is a pan-Asian strategic advisory firm providing advice and assistance to multinational companies and governments on succeeding in emerging Asia.