This is true more times than not: Locating a facility near a booming metro is as good if not better than locating it in the middle of that metro. Take Medina County, Texas, on the west side of San Antonio. Businesses there benefit from being on the I-35 Corridor just 150 miles north of the Mexico border on the side of San Antonio that still has abundant room for development. The county’s other main highway, US 90, running east-west, is being widened from four lanes to six.

Medina County Judge Chris Schuchart, who takes an active interest in the county’s economic development prospects, explains the significance: “I joke with San Antonio lawyers that I could drive from [Medina County seat Hondo] to the Bexar County Courthouse [in the heart of San Antonio] faster than most of them could get there. There’s nothing between me and there except a highway that’s not crowded.” And available, affordable land compared to northern and eastern San Antonio suburbs, says Schuchart. “It’s relatively inexpensive — perhaps $5,000 to $10,000 an acre. With Laredo down I-35, we’re just two hours from the largest inland port in America, and San Antonio is just 20 minutes from here.”

Lytle is the first town in Medina County heading out of San Antonio on I-35. Mayor Mark Bowen points to “a lot of land that is available and is still reasonable for manufacturing or other facilities — they certainly would have enough land on which to do that. We have a good workforce, a lot of people that live in the area.” Add a team approach to finding the right site to that list, says the mayor, nodding at Ruben Gonzalez, Go Medina County Community Partnership’s point man in Lytle. “We consider ourselves an extension of San Antonio,” says Gonzalez. “We’re serviced by CPS Energy, so we have the same electrical capability as the city.”

And a lot more, for a town of its size. A recent study found that 864,000 people live within a 30-minute drive of Lytle; the town has the best property tax rate in the area, at $0.42 per $100; an ample supply of large commercial tracts along I-35 for manufacturing and distribution; and a growing supply of residential real estate.

A Powerful Advantage

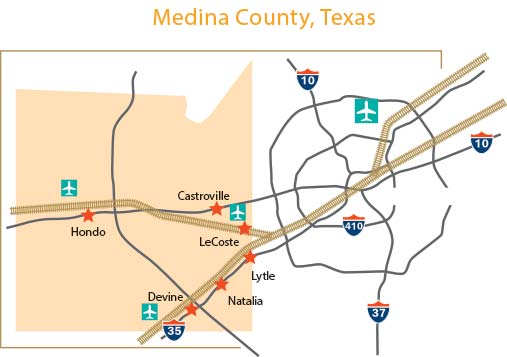

Still, for all its strategic significance to Medina County and the San Antonio metro area, about 10 miles of I-35 run through the county, in its southeastern corner. US 90, however, crosses the central part of the county, leaving Bexar County, through Castroville and Hondo to points west. Union Pacific rail runs east-west through the breadth of the county, and a north-south line is also adjacent to I-35.

Trade-related traffic to and from Mexico has precipitated infrastructure improvements in Medina County, which at the same time is absorbing San Antonio growth on the city’s western side.

“That’s the reason everyone is being very proactive in terms of infrastructure,” says Gonzalez, who spent time working in the San Antonio Chamber’s economic development office. “One of the biggest things companies were excited about was being on our own electrical grid. We’re completely separate from everybody else in the United States.”

Power supply and cost are of paramount importance to data centers, and Microsoft happens to be building one on the Medina-Bexar County line, north of Lytle. “Medina Electric Cooperative also does a great job,” adds Gonzalez. “That’s the reason we’re having so much success inside the county — we have a good solid electrical grid. That’s a really important point.”

Vulcan Materials, the nation’s leading producer of construction aggregates — crushed stone, sand and gravel — is preparing to open its largest facility yet and its second in Medina County. The quarry will serve the Gulf Coast market, says Tyler Lowe, manager of community and government relations. “We’re really looking forward to this being a crown jewel facility for us to produce a lot of materials and supply, essentially for the greater Texas market,” Lowe explains.

Why Medina County?

“A few things jumped out about Medina County,” says Lowe. “Certainly, it’s a business-friendly environment. County leadership has been great. Each city we work with is excited to have us there. They see the value of business for their citizens and for the growth of the county.”

Proximity to San Antonio is a major advantage to Vulcan Materials, notes Lowe.

“That accessibility for us is particularly huge. Obviously, being in the construction aggregates business, we see that growth coming toward Medina County. So it gives us accessibility to San Antonio, for both shipment of our products into there, and it’s also near where that growth is coming. Also, not being in San Antonio, we don’t have to deal with some of the traffic congestion that’s part of being in the middle of the city. It’s nice to have that accessibility without being in the thick of it. And when it comes to quality of life for workers, it’s huge to have that accessibility, but at a lower cost — and maybe a little bit better pace of life.”

A Warm Welcome Seals the Deal

Hondo is a long way from Renton, Washington, and other aircraft assembly locations in the United States. But aircraft assembly does take place in Hondo, thanks to a Brazilian aircraft manufacturer that picked the South Texas Regional Airport there — a former air force base — as the location at which to build and test its Colt light sport aircraft.

Texas Aircraft founder Matheus Grande explains: “A lot of pieces came together for us to end up in Hondo. We initially looked at California, Texas and Florida. One of the reasons we went with Texas was the strong former military workforce. It’s good to have former military personnel, because they’re very disciplined, and hiring them is a way to give back after the job they did for the country.”

Grande says he focused on locations in the Houston-Dallas-San Antonio triangle for logistics and workforce availability reasons, visiting many airfields in the region but not finding the ideal location. A legal advisor involved in the site search mentioned the Hondo airport, and the rest is history.

“I came to visit Hondo, and when we met the city authorities, we were very warmly welcomed,” recalls Grande. “This is what we were looking for — not only a reasonable rent and a nice hangar, but a city that would really welcome us and help us to make it happen. We dealt with other cities, and we had the chance to meet with different authorities. But here, they really wanted to help us to make Texas Aircraft successful. The city was super helpful to us and did their best to help us to move in.”

Texas offers a range of financial incentives, notes Grande, but being a self-funding company, those were of less interest than other benefits, such as assistance in refurbishing the hangar space and assisting with licenses and permits. Other location benefits include four runways and uncrowded airspace. “Every aircraft that comes out of production needs to do flight testing, and this is a very safe place to be,” says Grande. “We didn’t want to be in a crowded airspace — it’s very calm here with very friendly people around.”

Proximity to San Antonio’s international airport makes it easy to get back and forth to Brazil, where Texas Aircraft’s R&D takes place. Grande makes that trip many times per year.

Other aviation businesses at the Hondo airport include Corrigan Air Center, which performs interior completion services and exterior finishing on aircraft ranging from light turboprops to large business jets, and Hondo Aerospace, which specializes in aircraft part harvesting and storage.

‘We’ll Make it Happen’

These and other businesses found in Medina County the people, the space and the business climate that enabled them to do what they do sooner rather than later. Medina is home to plenty of workers — military and not — who would prefer not driving into San Antonio, notes Terry Dickerson, a developer in Castroville with deep roots in the county. Property in the county is among the most affordable in the metro area, and county officials will make becoming operational a snap, he relates.

“We want good corporations to come in that want good people, like our veterans, many of whom are just in their 40s and want to work,” says Dickerson. “They have a good military background. And then you have the farm boys that are tired of farming, or their daddy sold their farm to a developer. But if a project wants to come to the county, we’ll make it happen. Our county commissioners and our county judge are pretty savvy businesspeople. They’re going to make good, wise decisions. They’re the type that if they don’t think a [project] will work, they’ll tell you. They’re not going to run you around. Red tape would not be an issue, especially if it’s a business we feel is legitimate and will be here to stay.

“I would tell any CEO,” Dickerson continues, “if you want to live in a nice place and have all the conveniences of a big city and have a good school district, for the kids and for the parents that will be working there, you can’t beat Medina County — quote me on that. If you’re a good CEO, the first thing you have to think about is your employees. If they’re not happy where they live, they’re not going to be happy at work.”

This Investment Profile was prepared under the auspices of Go Medina County. For more information, visit gomedinacounty.com, or call (830) 444-2208