As one of the nation’s leading crop producers, Kansas has proved to be a fertile laboratory for what a top official of the Kansas Water Office likes to call progressive farming. A self-described “ag kid who went to engineering school,” Weston McCary, the Water Office’s technology projects coordinator, brings to his job a wealth of experience in both the agriculture industry and academia.

“People don’t truly realize how agriculture has evolved,” he says. “A lot of folks believe it’s still mom and pop out there with a pitchfork. We have drones that are flying themselves. We’re using satellite imagery to manage our crops and sensors to manage irrigation. We just had a guy from NASA out here talking about all the things we can do from space. It is standard issue now. It’s how we do ag.”

As director of precision agriculture at Northwest Kansas Technical College in Goodland, McCary instituted programs that preached the use of technology in the name of sustainability, “the ins and outs,” he says, “of how we do center pivot irrigation, subsurface irrigation, soil moisture probes, drones, GPS, guided tractors and all those things that are parts of soil conservation.”

“These are not a bunch of hippies. These are Kansas farmers.”

— Weston McCary, Technology Projects Coordinator, Kansas Water Office

Out in the field, McCrary has tapped into tech while managing a “Water Technology Farm” under a Kansas-wide public-private partnership spearheaded by the state. He also has seen progressive agriculture enter into the mainstream: Witness the embrace, he points out, of heretofore novel methods of promoting soil integrity by the biggest makers of farm equipment. It’s getting the word out to thousands of Kansas farms that perhaps is his biggest challenge.

“It’s a lot about education,” he says. “There’s something about a good old farmer that wants to have their hands on everything. But the truth is, if you can have a machine do what you would do on your best day and do it over and over and over, you can see that there’s a place for technology to do those redundant, menial tasks that humans don’t need to be doing.”

Leading the Way on Water

Western states that are struggling under sustained drought conditions could look to the example set by Kansas, whose bountiful agriculture industry relies heavily on the Ogallala Aquifer. The nation’s largest such source of underground water, it stretches more than 175,000 square miles and sustains farms throughout western Kansas. According to a recent report by two Kansas State University agricultural economists, the aquifer adds some $3.8 billion to western Kansas land values.

“It’s a large, substantial number, and it provides evidence of just how valuable irrigation is in western Kansas,” said Gabe Simpson, an associate professor in K-State’s Department of Agricultural Economics.

With a goal of reducing stress on overtaxed sources of precious water like the Ogallala, the state created a series of water management districts, known as Local Enhanced Management Areas. With public input and deference to local concerns, plus the technical expertise and buy-in of industry, academics and the state government, the LEMA districts have served to produce an impressive 25% water savings, McCary says, while at the same time enhancing the profitability of associated farms. The keys to such achievements, he believes, are a growing awareness of the pressing nature of water issues and the increasingly widespread adoption of easily available and usable technology.

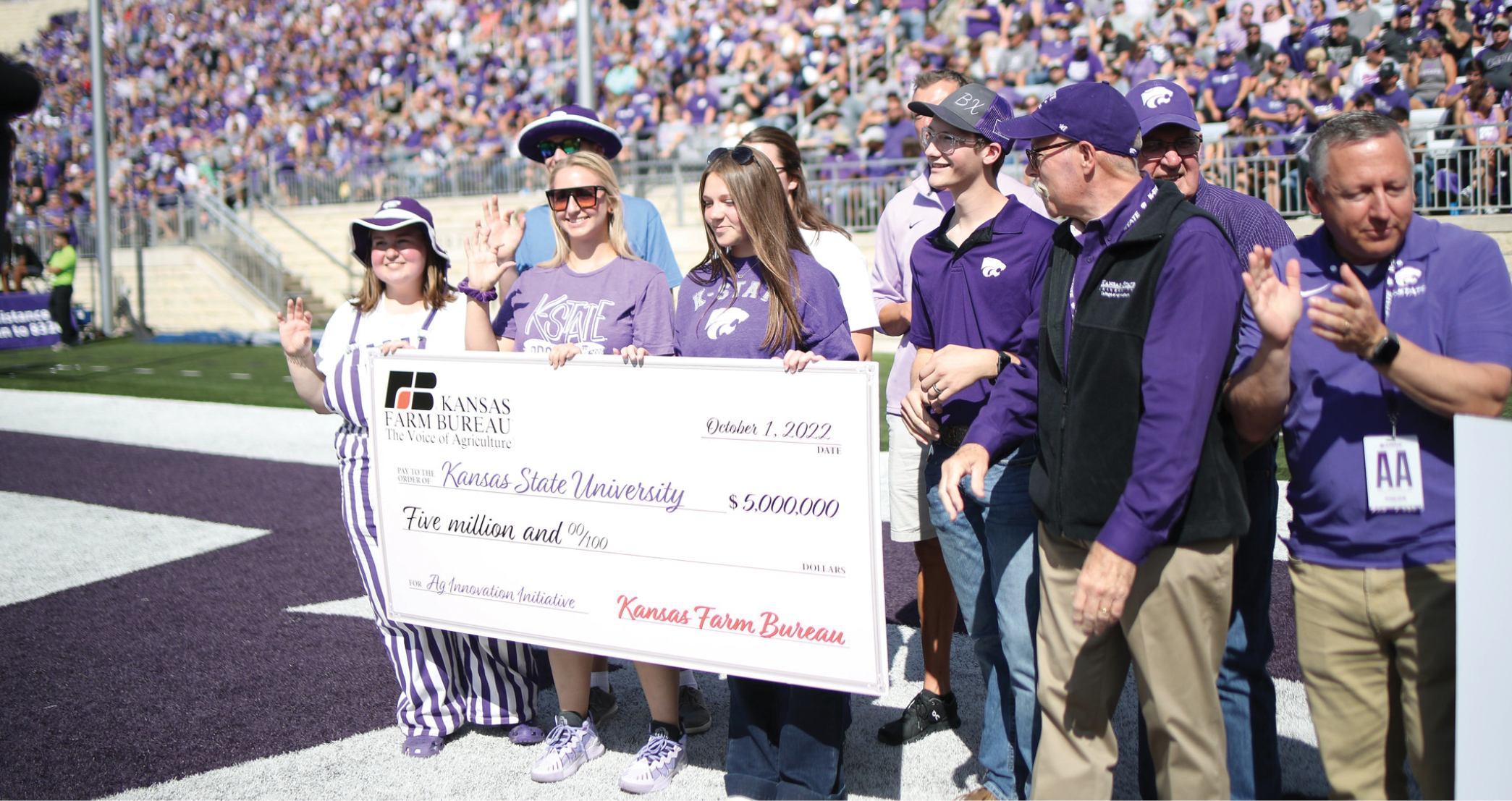

The Kansas Farm Bureau presents a record check.

Photo courtesy of Kansas State University

“Our pivots out here are all controlled from a cell phone instead of going out and starting 30 pivots manually, like we did when I was a kid,” he says. “We can start up, shut down, change rates, monitor, everything. Right from our phone. We can read the nitrogen in the plant as the pivots are going over the crop, and we can speed them up or slow them down. It all serves to make our water usage that much more efficient and make farming more profitable.”

McCary is leading the state’s new Water Innovation Systems and Education (WISE) program with partners that include Kansas State University. Ultimately, he envisions a series of strategically placed demonstration projects to showcase the evolving face of agriculture.

“We’re going to start growing some other products to diversify our financial portfolios, like everybody does when they invest. We have guys that are putting cover crops down and building better soil health while getting all kinds of secondary returns. They’re using less water while they’re getting twice the economics out of their fields. And these are not a bunch of hippies,” McCary says. “These are Kansas farmers.”

Record Gift to Kansas State

Kansas State, which opened in 1863 as the nation’s first operational land-grant university, consistently ranks among the nation’s top 10 schools for agriculture.

K-State offers an undergraduate degree in Agricultural Technology Management, with 95% of recipients receiving job offers before graduation.

“The goal of the ATM program,” says a K-State release, “is to educate technology managers who can combine the critical understanding of agriculture and biological sciences with the problem-solving viewpoint of an engineer.”

Located in Manhattan, K-State’s ag school boasts average annual research expenditures of $88 million. Sixteen undergraduate majors also include Agricultural Economics, Animal Sciences and Industry, Dairy Science, Equine Science and Feed Science and Management. Combined graduate and undergraduate enrollment has grown to 2,600.

In October 2022, the Kansas Farm Bureau pledged $5 million over five years to support the K-State College of Agriculture’s innovation centers for grain, food, animal and agronomy research. It’s the largest such donation in the organization’s history. The investment is to fund new facilities, renovations of current buildings and improvements in technology and equipment.

“This gift,” said Ag School Dean Ernie Minton, “is proof of the strong, longstanding relationship between the university and agriculture industry, which is the lifeblood of Kansas.