Many of the world’s special economic zones have a storied past linked to ports, airports and rail hubs. But zones today are focused on the future, whether that means expanding a port, catering to particular subsectors, implementing innovative new programs, constructing new infrastructure or welcoming startups to smart cities such as Masdar in the UAE; Mahindra World City in Chennai, India; or the new development taking shape in the Clark Freeport Zone north of Manila in the Philippines.

Reliable apples-to-apples project and investment data across the world’s thousands of zones still proves challenging to collect and verify. But this year Site Selection once again ranks U.S. Foreign Trade Zones based on a matrix of calculations derived from data in the program’s annual report to Congress released late in the summer. And we welcome to our pages this special contribution on global zones trends and innovations from The Adrianople Group’s James Forster. — Adam Bruns, Managing Editor

In the USA, Foreign-trade Zones (FTZs) serve a reasonably singular purpose in their operations: Reduce customs tariffs. They are secure areas that operate under the supervision of the US Customs and Border Protection agency (CBP) but are considered outside of its territory once operational. They have financial benefits and contribute to international trade and economic growth.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) vary in shape, size, and function, and can be described as business parks or cities that have regulations and tax incentives different from those of their parent country.

Comparing FTZs and SEZs is like comparing apples and oranges. All FTZs are a specific type of SEZ exclusive to the United States. All SEZs outside the U.S. operate differently from FTZs. An SEZ abroad could choose to function entirely the same as an FTZ (in terms of providing the same financial incentives), but an FTZ cannot provide the incentives that global SEZs can.

One key difference between FTZs and SEZs is that FTZs are seeking to promote the growth of established businesses inside of America, whereas SEZs are generally seeking to attract foreign investors. FTZs bring tax and import/export incentives to established businesses with infrastructure already in place (such as warehouses, ports, manufacturing plants, etc.). This results in consistent, predictable, and modest returns. A primary goal is to subsidize costs to enable U.S.-based businesses to compete with foreign businesses — “Made in China” manufacturing, for example.

By contrast, global SEZs take a different approach by often creating the park first, then renting space out to tenants. In other words, they are conducive to FDI. Tenant attraction incentives vary greatly, and this is where SEZs offer significant flexibility that FTZs cannot. A lesson can be learned from SEZs when it comes to creating one’s own opportunity.

Here are a few ways non-U.S. zones are redefining the boundaries of SEZs and showcase potential trends we will see over the next decade.

Seizing Opportunity Under

Seizing Opportunity Under

Contradictory Principles

The Kingdom of Lesotho’s national laws prevent local cannabis possession, consumption and distribution. Yet, when the enclaving South Africa decriminalized cannabis, the president of Lesotho ripened the country’s natural terrain for export. The government created the Mafeteng Special Economic Zone, the country’s first SEZ and the first and only in the world to farm medical cannabis.

The zone has created a job market and enabled knowledge transfer in a nation where 24.6% of the population is unemployed. Indeed, Bophelo Bioscience, the sole tenant of the Mafeteng SEZ, has become one of the largest operations in the country. Halo Collective Inc, a Canadian company, acquired the firm in 2020. It has already planned four expansions.

Furthermore, it is capturing an industry that previously operated in the informal economy. Throughout the 2000s, 70% of South Africa’s cannabis was imported from Lesotho. The share of exports which is now regulated through production licenses has increased and cannabis has become the largest cash crop in Lesotho.

In addition to reduced corporate tax, the government prioritizes responsiveness to any export needs of the operating company. They are wholly supporting the industry and removing as many hurdles as possible for investors.

Biotech Zones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is infamous for costly and lengthy procedures to bring biotech to the market. U.S. firms such as Minicircle, which is researching gene therapy to cure HIV, have relocated to an SEZ in Central America with favorable regulations, costs and approval processes.

Genome Valley in India is an industrial area that is home to three SEZs that house approximately 200 biotech companies and creates one-third of India’s vaccines. After a successful pilot zone, the $60 billion Hainan Medical Zone will allow patients to try untested drugs through streamlined application processes.

A study by the Adrianople Group found that over 80 SEZs are catering to the biotech industry, with as many as 24 expected to open in the next five years. Indeed, the global biotech industry market size was valued at $1,372 billion in 2022 and is expected to nearly triple by 2030 at a CAGR of 13.9%.

SEZs offering streamlined processes, drug import and export incentives, and preferable R&D regulations are primed to attract multinationals and succeed.

Education in Zones

Locating universities inside SEZs has long-term benefits for the growth of a country, as well as for SEZ success.

The Kigali Special Economic Zone (KSEZ) in the capital of Rwanda is home to Carnegie Mellon University Africa, a world-renowned and highly selective university. Here, SEZ tenants are within touching distance of the best local talent pool in the country. What’s more, over 50% enrolled in CMU-Africa are Rwandan. By providing locals with the best education, Rwandans are going to help Rwanda grow in the long term.

The initial success has already led the Rwandan government to announce Kigali Innovation City, a master-planned expansion inside the KSEZ, which will contain three more leading African universities. Creating entrepreneurial knowledge hubs inside of SEZs results in young, ambitious and educated individuals collaborating to solve the nation’s and world’s problems. By circumstance, they’ll be informed of local SEZ benefits and the infrastructure already in place, understand the benefits of starting businesses inside them and have immediate access to the necessary contacts.

In a similar vein, Dubai Knowledge Park (DKP) and Dubai Academic City (DAC) act as campuses for 27 international universities. These universities are primarily from native English-speaking countries such as Australia, Ireland, and the UK. As of September 2022, 85% of the 28,200 students were international. Generally, international students are only temporary residents, but it can be hard to ignore a positive trickle-down effect. Students who enjoy their time abroad are more likely to return, as well as promote the local economy during their stay. The de facto business language of the world is English, and selecting universities from native-speaking countries is no coincidence.

DKP is strategically situated adjacent to Dubai Internet City, which is the nation’s tech hub and includes tenants such as Microsoft and IBM. Additionally, DKP offers specific incentives to attract companies whose mission is professional development. These include human resource management, recruitment, consultancy, executive search and vocational training companies with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa regions. The UAE government is attracting and developing a deep knowledge base of a region where they are keen to see investment. Knowledge is a resource and education is the strategized industry that creates it.

Digital Nomads

Post COVID-19, many employees have experienced a taste for remote work and no longer wish to return to the office full-time. With this, a surge in digital nomads is occurring. Digital nomads are online workers, freelancers or entrepreneurs who are generally paid in hard currencies and, being location independent, choose to live in countries where the cost of living and personal income taxes are lower, while the expatriate quality of life is higher.

While most SEZs don’t have residential areas to accommodate this new type of worker, some countries have already begun schemes to attract them. The aptly named Digital Nomad Village (DNM) on the Portuguese islands of Madeira is an initiative launched by the regional government and Startup Madeira. Many cryptocurrency enthusiasts (enjoying no capital gains tax) and expatriates (earning over four times the minimum wage — visa requirement) reside on the island, which itself is a free port. Approved by the European Union, Madeira’s International Business Center handles all business jurisdictions, and the island also has its own governmental bodies in parliament and regional government.

While most SEZs don’t have residential areas to accommodate this new type of worker, some countries have already begun schemes to attract them. The aptly named Digital Nomad Village (DNM) on the Portuguese islands of Madeira is an initiative launched by the regional government and Startup Madeira. Many cryptocurrency enthusiasts (enjoying no capital gains tax) and expatriates (earning over four times the minimum wage — visa requirement) reside on the island, which itself is a free port. Approved by the European Union, Madeira’s International Business Center handles all business jurisdictions, and the island also has its own governmental bodies in parliament and regional government.

The degree of DNM’s success shocked the government and led to the project being extended through to 2024. Mainland Portugal has seen the benefits and doubled down. In October 2022, the country announced the aptly, but not-so-imaginatively, named “residence visa for the exercise of professional activity provided remotely outside the national territory.”

With this, Portugal aims to gain an early market share of digital nomads as a commodity. Over 40 countries have digital nomad visas. The U.S. does not have one. Many SEZs with one-stop shops have integrated customs offices to process dedicated business visas with efficiency. An opportunity exists for countries to launch SEZs resembling beach resorts or hi-tech planned communities, with simple and quick visa processing times, low personal income tax, and incentives to stabilize digital nomads into long-term residents or serial entrepreneurs.

These examples showcase the flexibility with which zones can operate. By no means is this an exhaustive list. There exist SEZs that exclusively create environmental technologies to tackle climate change, carbon-neutral SEZs, SEZs that independently handle cryptocurrency exchange regulations, and many more. If a nation has an economic conundrum, there’s a chance that an SEZ can solve it with policy experimentation. What’s more, SEZs are optimal for test-bedding general policies in a controlled environment before launching nationwide.

Now, all of this is not to say that the U.S. should replicate the zone strategies mentioned here. On the contrary, successful SEZs are created on a case-by-case basis responding to the location’s needs and infrastructure. The “one-policy-fits-all” approach rarely works, and policy experimentation needs to be calculated.

Should they idle, one of the biggest risks the United States of America faces is losing American-founded startups to early-stage relocation. Indeed, Startup Cities are popping up all over the world, and it won’t be a surprise if the next Apple, Amazon or Alphabet starts in a special economic zone. How much opportunity cost can the U.S. afford by not engaging in SEZs?

Texas Tops FTZ Rankings

The Texas Association of Foreign Trade Zones reports that the state’s FTZs employ nearly 50,000 people — more than 10% of the 480,000 employed in the nation’s 258 approved FTZs. Port Houston set yet another new container record in September. Port Freeport in October welcomed news that Volkswagen Group of America has signed a 20-year lease to create a new Gulf Coast hub for vehicle logistics port operations, creating 113 jobs. And AllianceTexas in the DFW region continues to innovate and grow at one of the leading industrial developments in the nation.

Over 480,000 people were employed within 1,200 active U.S. FTZ operations in 2021, when the value of shipments into zones totaled over $835 billion.

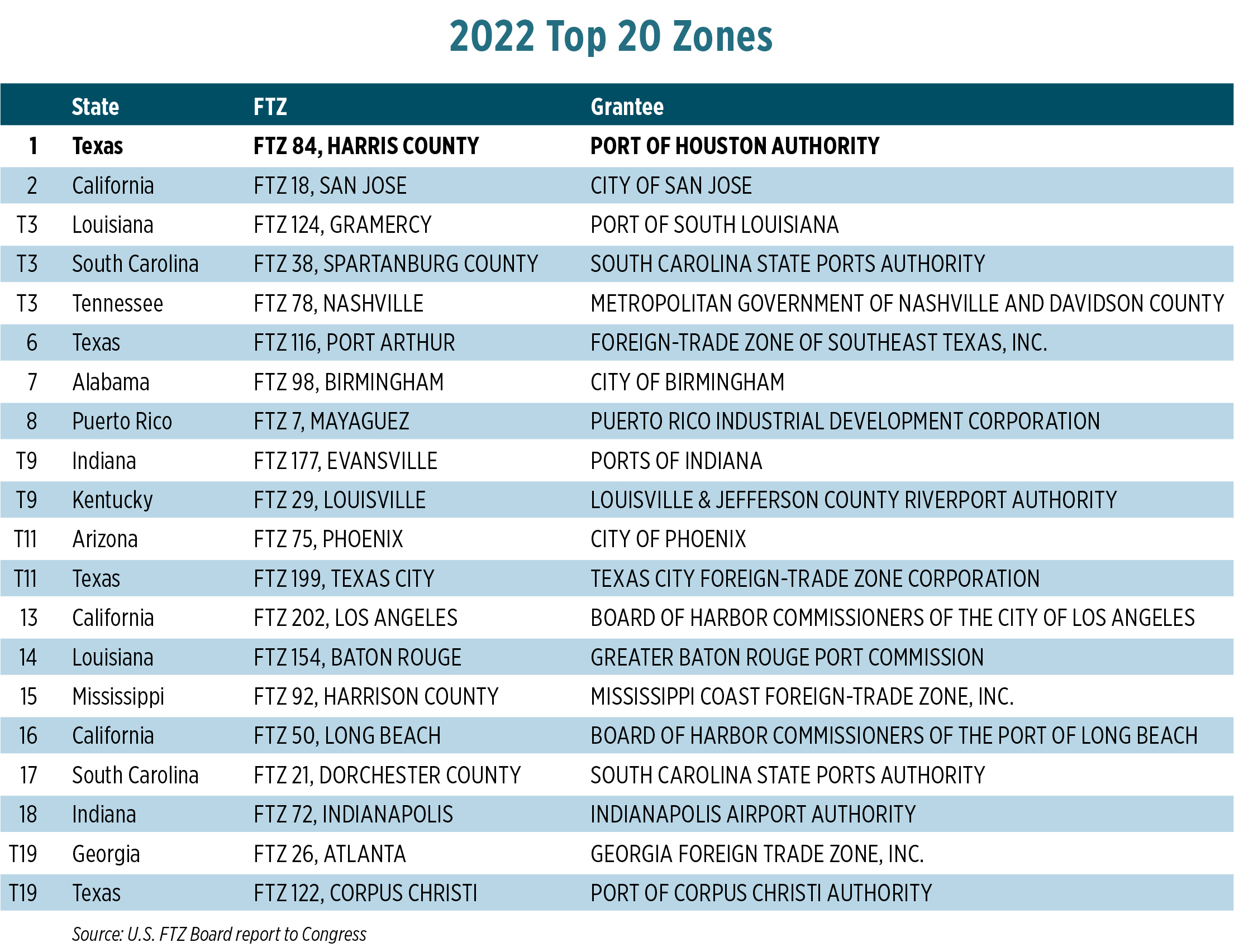

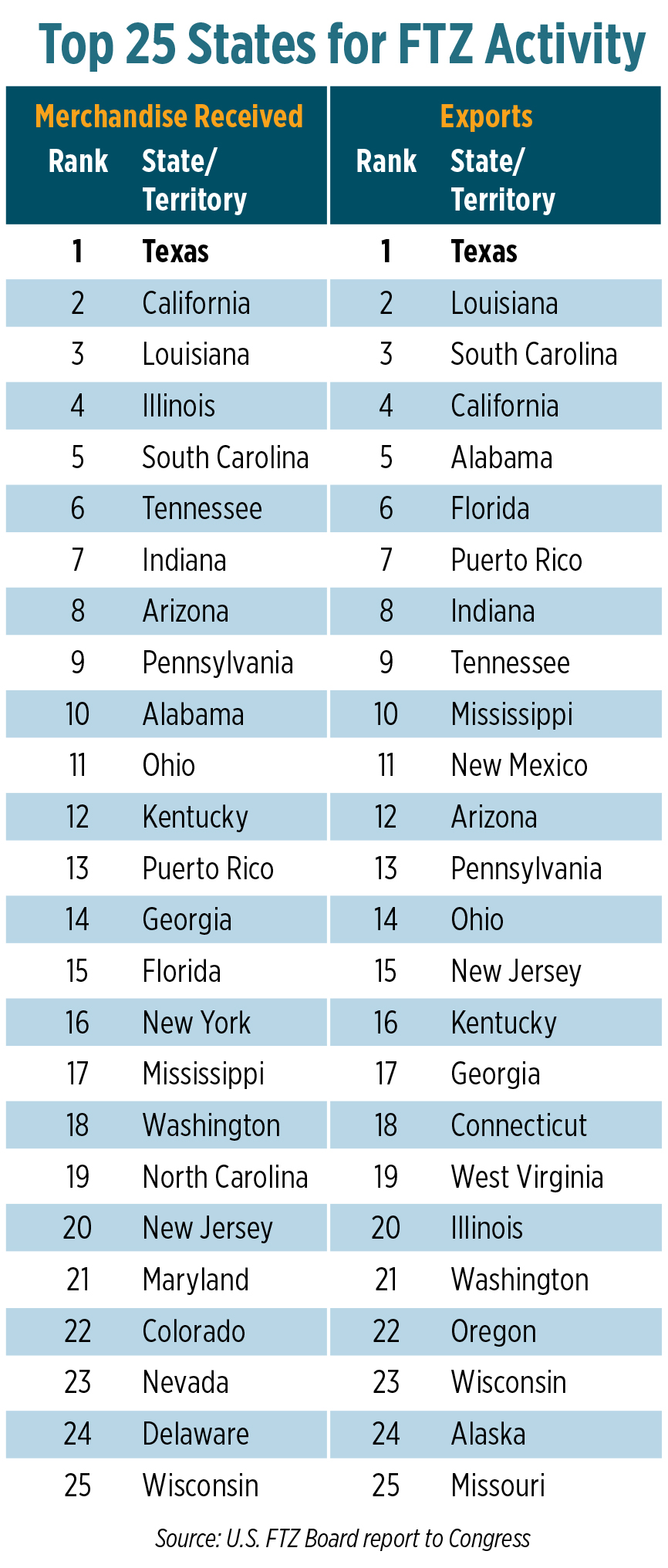

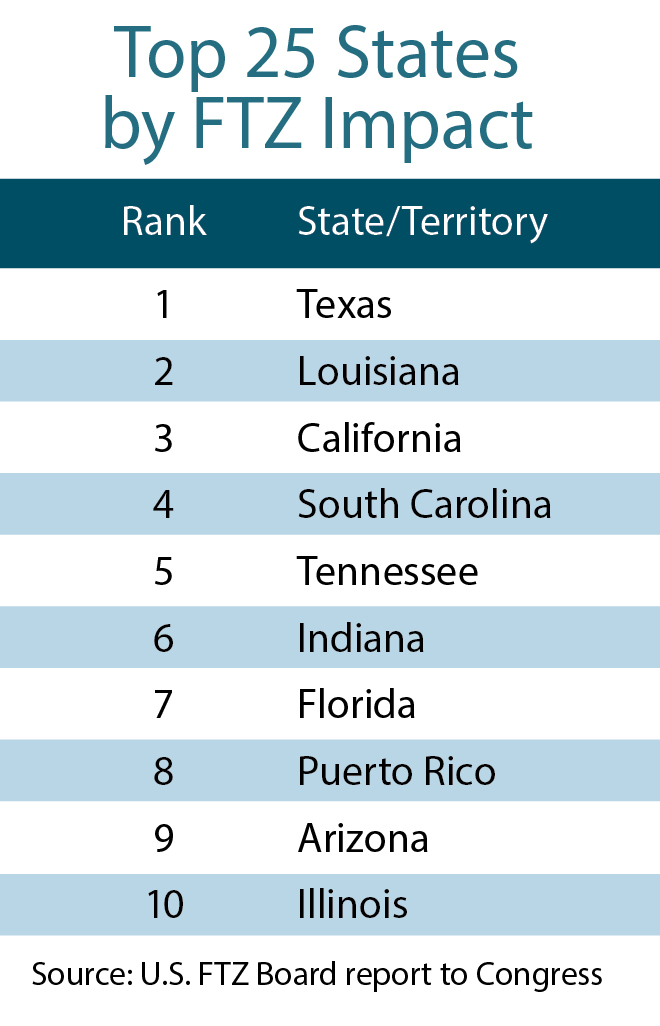

Consider all of that, and it’s no surprise then that this year’s Site Selection rankings of FTZs find Texas to be No. 1 in FTZ impact, as well as No. 1 in several FTZ categories. Four of the top 20 FTZs by total impact are in the state, starting with No. 1 Port Houston.

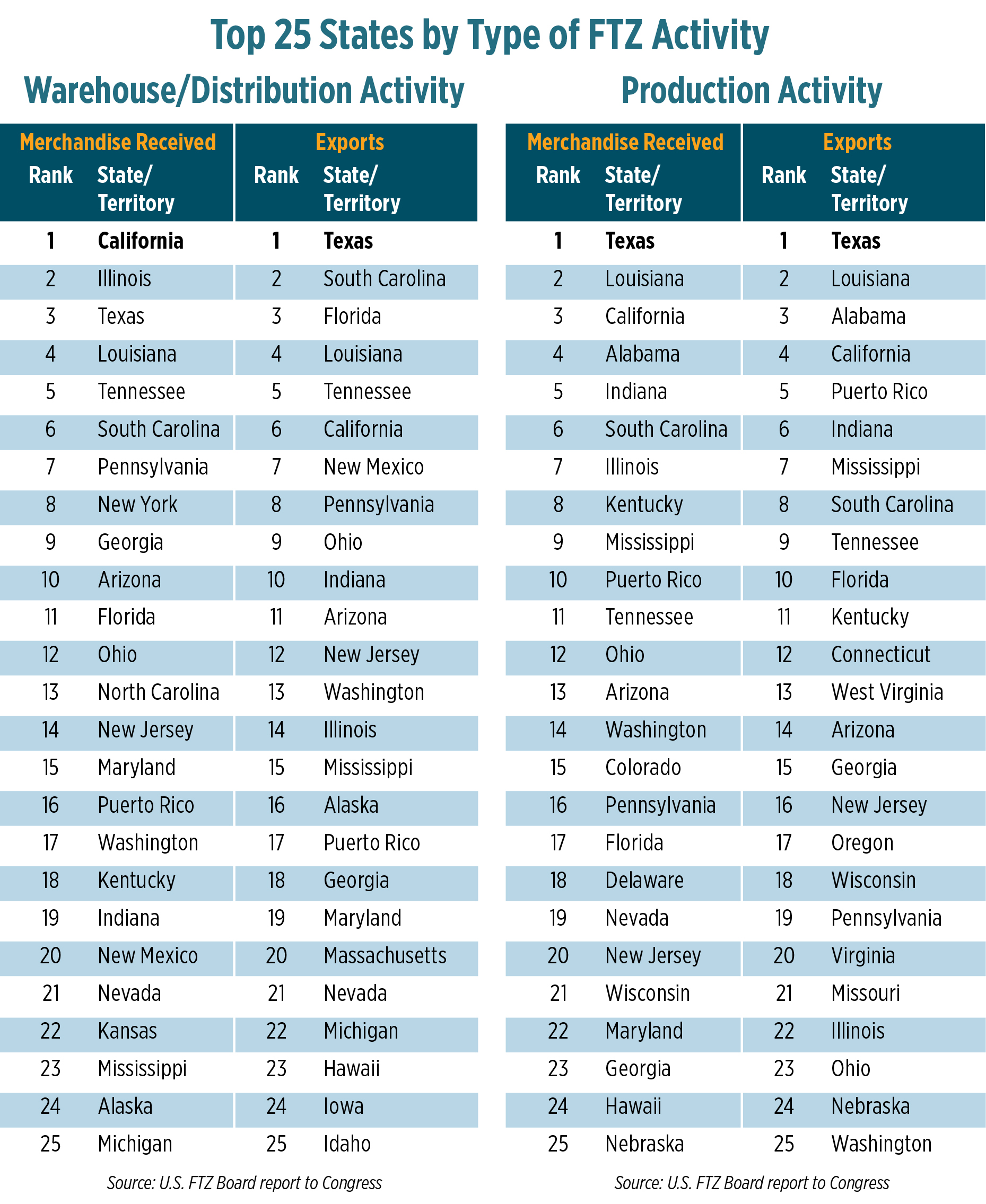

As in past years, the Conway Data research team (Daniel Boyer, Karen Medernach, Brian Espinoza and McKenzie Wright) extracted relevant jobs, manufacturing and merchandise received/exported data from the latest U.S. FTZ Board report to Congress (published in August 2022) in order to rank the Top 10 States by Total FTZ Economic Impact and Top 20 U.S. Foreign-Trade Zones by Economic Impact. The charts here also display top zones by category.

“There were 197 FTZs active during the year, with a total of 356 active production operations,” the report to Congress says of FTZ activity in 2021, which included 1,200 active operations overall. The value of shipments into zones totaled over $835 billion, compared with nearly $625 billion the previous year. “About 65% of the shipments received at zones involved domestic status merchandise,” the report states.

Warehouse/distribution operations received over $369 billion in merchandise while production operations in such industries as pharmaceuticals, oil refining, automotive, electronics and machinery/equipment received more than $465 billion (56% of zone activity). Exports from facilities operating under FTZ procedures amounted to over $123 billion, a figure that does not include certain indirect exports involving FTZ merchandise that undergoes further processing in the United States at non-FTZ sites prior to export, the report explains.

There’s no better example of FTZ impact than Port Houston, which Texas Gov. Greg Abbott visited in October to get an update on developments such as Project 11, the $1 billion widening of the Houston ship channel. Port Houston’s container facilities handle nearly 70% of all U.S. Gulf Coast container traffic, and the port hosts one of the nation’s largest petrochemical complexes. Port Houston Executive Director Roger Guenther noted that “nearly 50% of Texas’ waterborne tonnage comes through the Houston Ship Channel.” The federal waterway supports more than $800 billion of U.S. economic activity.

There’s no better example of FTZ impact than Port Houston, which Texas Gov. Greg Abbott visited in October to get an update on developments such as Project 11, the $1 billion widening of the Houston ship channel. Port Houston’s container facilities handle nearly 70% of all U.S. Gulf Coast container traffic, and the port hosts one of the nation’s largest petrochemical complexes. Port Houston Executive Director Roger Guenther noted that “nearly 50% of Texas’ waterborne tonnage comes through the Houston Ship Channel.” The federal waterway supports more than $800 billion of U.S. economic activity.

“The ongoing work of Project 11 to widen and deepen the nation’s busiest waterway,” said a release from the port, “will allow for safer and more efficient two-way vessel traffic, delivering more goods, cargo, jobs, and economic prosperity for Texas and the region.” — Adam Bruns