Vietnam’s inexpensive and productive labor force has oftentimes earned it the title of the ‘Next China’. With its dramatically smaller population, size and an economy lacking diversified upstream and downstream supporting industries, Vietnam never genuinely had the ingredients to rival China as an investment destination. Although vastly smaller in size, the country is experiencing a similar rapid development as it comes of age. As traditional Vietnamese investment locations become saturated and less competitive, investors need to keep in mind the lessons learned in China as it tried to absorb billions of dollars of investment over a short period of time so as not to be trapped in locations which may quickly lose their attractiveness.

Foreign manufacturing investment in Vietnam began slowly in the late 1990s. The first waves of investors, primarily small-scale Taiwanese, Korean and Japanese companies, arrived to set-up operations and take advantage of a very low-cost place to do business. This happened as China was experiencing its second decade of double-digit growth. By the late 2000s, the Vietnamese economy achieved its own double-digit growth and rising per capita income, fueled by foreign direct investment (FDI). Much of this investment growth was driven by companies seeking lower operating costs as China’s seemingly inexhaustible labor market began to tighten with rapidly rising wages in traditional coastal manufacturing locations. With China becoming less cost-competitive, Vietnam emerged as the next logical destination for manufacturing investment. Its abundant, underemployed and cost-effective labor force earning minimum wages of about US$45 per month attracted investors from garments, textiles and shoes and, more recently, electronics assembly.

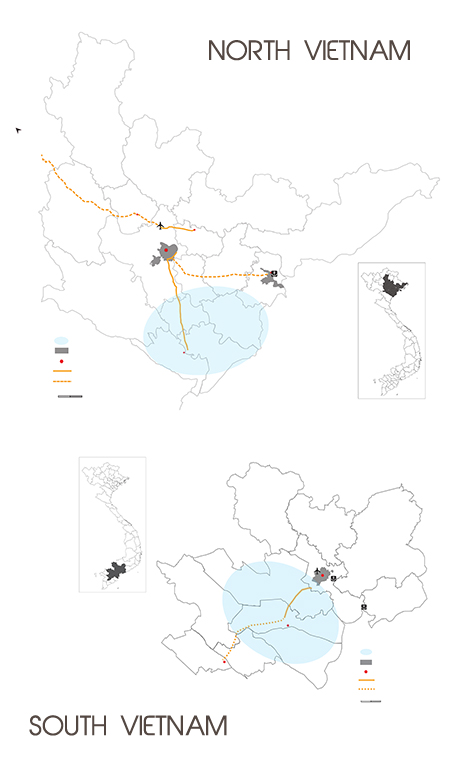

Like China more than a decade earlier, manufacturing investment in Vietnam is concentrated in and around its largest cities, Hanoi in the north and Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC, formerly Saigon) in the south. Over the last 20 years these areas absorbed over 55 percent of all of the investment to Vietnam, driven by the close proximity to a pool of managerial and technical talent, services, and key sea and air port infrastructure. The China-like torrent of investment into Vietnam, a country more similar economically and geographically to China’s Yunnan province, peaked in 2008 with investment inflows of US$9.5 billion. This tidal wave of investment in and around Hanoi and HCMC disproportionately affected the dynamics of its labor, property and other markets. Now, these cities are experiencing labor shortages requiring recruiting activities in distant provinces and wage inflation. Higher salaries have not been able to offset the labor shortages as the cost of living has trended in parallel, making it unattractive for some Vietnamese to relocate. This is also reflected in absenteeism in investment zones in HCMC after the Vietnamese Lunar New Year earlier this year. Absenteeism ranged from 30 – 35 percent while companies in provinces adjacent to HCMC reported shortages of labor averaging from 200 to 400 workers in each plant that took months to replace.

This tidal wave of investment in and around Hanoi and HCMC disproportionately affected the dynamics of its labor, property and other markets. Now, these cities are experiencing labor shortages requiring recruiting activities in distant provinces and wage inflation. Higher salaries have not been able to offset the labor shortages as the cost of living has trended in parallel, making it unattractive for some Vietnamese to relocate. This is also reflected in absenteeism in investment zones in HCMC after the Vietnamese Lunar New Year earlier this year. Absenteeism ranged from 30 – 35 percent while companies in provinces adjacent to HCMC reported shortages of labor averaging from 200 to 400 workers in each plant that took months to replace.

For example, Samsung’s smart phone factory in Bac Ninh province, near Hanoi, employs more than 20,000 workers. Despite being the salary benchmark employer in the province, the company needs to actively recruit staff from as far as 160 miles (257 km.) away. Vietnam’s business press regularly reports similar labor shortages in southern provinces clustered around HCMC. A survey conducted by Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment in October 2012, which included 500 Japanese companies, reported labor shortages in HCMC and the neighboring provinces of Ba Ria – Vung Tau, Dong Nai and Binh Duong and Hanoi. The pressure on labor supply in these magnet locations is also reflected in prevailing market wage rates. Vietnam’s minimum wage varies from $67 to $97 per month depending on geographic location. Prevailing market base wages range comparatively from $75 in the least developed provinces to $190 in Hanoi and HCMC. While the difference in minimum wage between the bottom two tiers and the top two tiers is about 45 percent, the difference between the minimum and market wages ranges between about 12 percent in the bottom-tier and 96 percent in top-tier locations. Following the higher wages in top-tier locations, investment is shifting from labor intensive to more value added activities, such as supporting industries and fast moving consumer goods that need to be located close to their largest markets.

As a result of these labor pressures, upcoming second tier locations are emerging as increasingly attractive alternatives as improved infrastructure allows easier access to locations with a better labor supply, lower labor costs and location-based investment incentives. Second tier locations need to be evaluated carefully though, as even the most promising locations with abundant labor may be subject to local government restrictions on labor intensive manufacturing – a paradox that is unique to Vietnam.

With a relatively low per capita GDP of $1,411 per person and still-developing manufacturing supporting industry supply networks, the Vietnamese government should be encouraging labor intensive industries like garments or textiles in outlying provinces. In some areas, however, even where there is a surplus of labor, provincial government agencies with autonomous responsibility for approving investment projects are rejecting applications for labor intensive manufacturing operations. In others, investment applications are subject to excessive scrutiny and, if approved, can be burdened with restrictions limiting the investors’ freedom of choice over site location or requiring unrealistic investment density ratios (expressed as the value of the investment in US dollars per square meter of land area).

Incentive policies are intended to encourage economic development focused on high value-added activities to move Vietnam up the global value chain. But this focus is premature and poorly implemented. The availability of investment incentives in Vietnam is based on either geographic location or qualification of the investment activity as high technology or “high-tech”. High-tech investments qualify for a four-year corporate income tax (CIT) exemption, a 50-percent reduction for the following nine years and then a reduced rate of 10 percent for two more years before returning to the base rate of 25 percent. However, the sectors and activities that qualify are only generally defined, and the qualification process is highly opaque; few investors have qualified, which is likely discouraging the very kinds of investors Vietnam is trying to attract.

Samsung Electronics Vietnam (SEV) is one of the few that qualified as a high-tech firm, but when they expanded, they were surprised by additional conditions that were imposed by the government in Hanoi. Although Samsung had invested $492 million, the government required it to invest another $1.5 billion and to make a commitment to investing 1 percent of its revenue in R&D. Negotiations reportedly continue, and the company has had to delay the construction of its next phase well into 2013.

Location-based incentives remain easier to qualify for, but are limited to a small number of provinces. Most are too far removed from infrastructure and sources of technical and managerial talent to be of practical interest to investors. Companies investing in provinces considered “areas of especially difficult socio-economic conditions” are eligible for a CIT holiday of up to four years, reduction to 5 percent tax for the following nine years, a favorable rate of 10 percent for two more years and, after that, the standard rate of 25 percent applies. Meanwhile, investments in “areas of difficult socioeconomic conditions” are eligible for a CIT holiday of up to two years, reduction to 10 percent for the following four years and a favorable rate of 20 percent for four more years before the standard rate of 25 percent applies.

Although the infrastructure in those provinces where investors qualify for incentives is usually seriously underdeveloped, Vietnam has made steady progress in improving its infrastructure with the central government earmarking up to 50 percent of the national budget on infrastructure development – well above the average for the world’s developing countries, but similar to China’s emphasis on hard infrastructure investments over the last two decades. Improvements in transportation infrastructure, in particular, are a priority for the government, and some impressive improvements have been made so far. While these improvements have so far been mostly limited to linking provinces adjacent to Hanoi and HCMC, they have reached some second tier locations with good labor supply and attractive incentives. Investors need to do their homework and evaluate the many available alternatives.

Vietnam continues to be attractive to manufacturing investors seeking lower labor costs and less than China and Indonesia; lower risks of flooding and political uncertainty than Thailand; more developed manufacturing infrastructure than Myanmar; and a larger labor pool than Cambodia. But its attractiveness is quickly leading to saturation in traditional hot spots for investment in and around Hanoi and HCMC leading to wage inflation, a tight labor supply and infrastructure bottlenecks reminiscent of those experienced in coastal China a decade ago. While the traditional investment destinations have lost some of their luster, like China, investors need to look to viable second tier locations, which three or four years ago, could not even be considered.

Dennis Meseroll (dennis.meseroll@tractus-asia.com) is a co-founder and executive director of Tractus Asia Ltd., where Antonio Sequeros (antonio.sequeros@tractus-asia.com) is a consulting manager. Tractus Asia is a leading Asia-based FDI advisory firm with offices in Ho Chi Minh City, Shanghai, Bangkok, Pondicherry, Jakarta and Yangon.