Plano, Texas, lies 20 miles (32 km.) north of Dallas. Once considered a Dallas suburb and now its own city of close to 300,000 residents, Plano rests near the northern apex of the expanding mega-region that loosely straddles Interstate 35, the federal highway that slices East Texas from the rest of the state, from the Red River, they say, to the Rio Grande.

Plano’s population having more than doubled since 1990, the city has enjoyed an attendant economic surge, driven largely by its ability to lure the national and regional headquarters of corporate heavyweights such as Intuit, Bank of America, Pizza Hut, Hewlett Packard, Liberty Mutual Insurance, JPMorgan Chase and, perhaps most famously, Toyota of North America, which announced its move from California in 2014 and completed it in 2017. Why so much love for Plano?

“We’re one of the safest cities in America that has a population over 250,000,” says Mayor Harry LaRosiliere, “and our school districts graduate 98% of our kids. Businesses want to bring their culture and their people with them, and those are two very compelling reasons to want to relocate here.”

Importantly, notes LaRosiliere, the public revenue those corporate facilities generate has afforded Plano the luxury of reducing property taxes, those being the fees that serve across Texas to offset the statewide absence of personal or business income taxes. Fifty-two percent of Plano’s property tax revenues, says the mayor, come from the business end.

“We’re no longer a sleepy bedroom community.”

Born in Haiti and raised in New York, LaRosiliere is in his second term as Plano’s first black mayor. When Site Selection quizzed him about one particular challenge posed by Plano’s growth, he was decidedly frank.

“We’re no longer a sleepy bedroom community. We are a thriving big city in America, and the notion that some people hold that we’re going to be just a suburb with single-family homes is not rooted in reality. That ship has sailed.”

It’s become a matter of space. Plano is “landlocked,” says LaRosiliere, by the concurrent growth of neighboring cities such as Frisco, Allen, McKinney and Garland. That physical limitation helped inspire the commissioning of “Plano Tomorrow,” a comprehensive growth plan issued in 2015 that, four years later, is tied up in court, challenged by local activists who maintain that its allowance for increased housing density threatens Plano’s “suburban character.” They want a referendum. The City says no.

“In order to remain relevant, you have to adapt,” says LaRosiliere. “Our many high-employment companies are attracting millennial workers, and they’re not looking for a 2,000 square-foot [185 sq.-m.] home. They want to live close to work and ride their bike there. They don’t want a 30- to 40-minute commute. So, the demand is for multi-family.”

And those opposed?

“Throw some cold water in their face,” says the Mayor, “and tell them, ‘Wake up.’ ”

New Braunfels: A Tough Road to Hoe

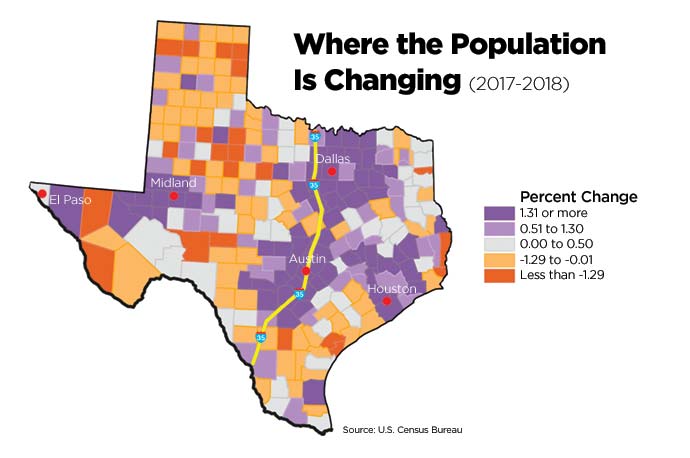

South of Plano, the I-35 Corridor passes through Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin and San Antonio and ends at Laredo, passing such upstarts as Waco, Georgetown, Round Rock and New Braunfels along the way. Some 11 million Texans, roughly 40% of the state’s population, live within the Corridor’s 22 counties, according to the Texas Dept. of Transportation. The value of goods passing through the Corridor is estimated to exceed $750 billion annually.

“There are almost too many investments to count.”

About halfway between Austin and San Antonio, New Braunfels (BRON-fuls, not BROWN-fells), has a history of manufacturing, with the diversified likes of Sysco, Martin Marietta, IBEX Global and Cemex now injecting jet fuel into the economy. For the 12 months ending in July of 2018, New Braunfels experienced population growth of 7.2%, the second-fastest rate in the country among cities with populations greater than 50,000, according to the U.S. Census.

Mayor Barron Casteel, 48, grew up in New Braunfels, and has seen the city swell from 20,000 residents in 1980 to 85,000 today. Casteel tells Site Selection that while the city’s dramatic growth has stressed local infrastructure, it’s forced the city to up its game. He cites a $500 million capital campaign that’s yielding municipal improvements across the board.

“There are almost too many investments to count,” Casteel tells Site Selection. “We’ve got about $45 million worth of local street projects. We’re doing sewer lines, water transmission lines, water towers. We’re putting in a new reservoir that’s actually underground. My water meter and my electric operate on smart technology, and I can operate them from my cell phone. I like that.”

In addition, says Casteel, the city is building a new police station, two new fire stations, a new ballfield and new jail. The schools are hiring teachers and bolstering security.

While growth, he says, is “a good problem to have,” Casteel sours on the subject of the Corridor. The stretch from Austin to San Antonio is one of the state’s most congested roadways.

“If these were arteries,” says Casteel, “we’d have cardiac arrest. As a region, our highways and roadways are extremely important. The more congestion we have, the greater it impacts our economic vitality. The more hours we have people sitting in congestion, the more the costs we will incur as a community. We’ll not have the location of good jobs and commercial investment that benefits all of us.”

Casteel believes the state wasted billions of dollars by building Interstate-30 roughly parallel to I-35, but without constructing a link between the two to better distribute traffic. He’d like to see voluntary toll lanes, but the notion is politically fraught. Officials at all levels of Texas government, Casteel suggests, have succumbed to a false perception that toll lanes constitute a road tax. A top official of the DOT suggests there won’t be toll lanes anytime soon.

“What we hear from our commissioner is that we’re in a non-toll environment,” says Brian Barth, the DOT’s director of project planning and development. “So, in terms of I-35,” Barth tells Site Selection, “the solutions we are working on are non-toll solutions.”

The DOT has proposed upgrades to sections of the highway northeast of San Antonio, including what it calls “management lanes” and improvements to several interchanges. A three-phase, $5.6 billion effort to speed traffic through Austin is to commence by 2022, Barth says, and might be completed by 2027. Nevertheless, Austin’s daily traffic volume is expected to increase 50% more by 2050, Barth says, with the state’s population likely to double.

“We, as a state, will have to take a multi-modal approach, including a lot of technology,” he says. “We do think that as technology evolves with autonomous vehicles, that will add capacity back into the system to meet those demands. We’re just going to have to turn over every stone to solve these problems. It’s not going to be the same way we’re doing things today.”

Midland: ‘We Cannot Stop’

Of the three Texas mayors we spoke with, Jerry Morales of the West Texas city of Midland faces the toughest challenge, and it’s probably not even close. Midland’s latest oil boom, the fruit of widespread adoption of hydraulic fracturing, has brought in tens of thousands of petroleum workers, all earning cash to burn. Midland is blazing. It has the nation’s second-fastest growing economy, according to Wallet Hub. Surrounding Midland County grew 4.3% by population last year, sixth highest in the country.

No one saw this coming.

“When oil hit $100 a barrel in 2014, it caught everybody off guard,” Morales tells Site Selection. “We’re still trying to catch up.”

Now, says Morales, the somewhat quaint town of his youth is “the true West Texas metropolitan city. We’re serving 20 counties around us with shopping, places to eat, recreation and other things. It’s exciting to see our community grow in that capacity of serving others.”

But the city, its population having swollen to more than 170,000, is straining under the weight of its load. Its schools are crowded and they need upgrading, 30% of its roads are broken beyond repair, utilities are stretched, and there’s a shortage of doctors and other professional workers. The town, says Morales, will need to pass a school bond, a healthcare bond and two road bonds. Even if it adds the 650 homes and 3,000 apartment units expected this year, Midland will need new housing as far as the eye can see; thousands of oil workers now live in trailer villages known as “man camps.”

“The builders,” says Morales, “can’t find people to work. Contractors, plumbers, they’re all six months behind. Getting material out here to West Texas, especially with the congestion, that takes time. There’s a three-to-six month wait on cement, and we’re having to share road contractors with the state. So, we’re thinking outside the box. We’re trying to be very business-friendly with builders.”

With so many needs, how does Midland prioritize?

“Our first focus,” says Morales, “is education. Our kids are important, and they’re our future.”

Further: “We’re sitting on billions of dollars of minerals. We cannot stop. We cannot stagnate. We will continue to build, and this will be a world-class city.