In sports it’s called a scouting report. Experts evaluate the factors that can make or break an athlete’s chance to compete, then make a report to the decision-makers. Several weeks ago, I sat down with two pros who are acknowledged experts on Southeast Asia to get their take on the future of manufacturing in the region.

Scott Ellyson and Jeff Sweeney are industry veterans, the founding partners of East West Manufacturing, an Atlanta, Georgia-based global contract manufacturing company. East West is the equivalent of a five-tool company, with expertise in engineered products, electronically commutated (EC) motors, electric motors, medical products and electronic manufacturing services (EMS). The company operates manufacturing facilities and engineering offices in China, Vietnam and India, and has partner factories in China, Thailand, Vietnam, Taiwan and India.

They’re bright guys, with a penchant for interrupting each other. The conversation is lively and meandering as they discuss where they see manufacturing investment headed, and run down a checklist of criteria when considering investing in the region.

Pins in the Map

Myanmar really gets them talking. If not bullish, they certainly sound intrigued by the prospect of investing there. “They have a leader who understands international, who isn’t a protectionist, who wants to put fair laws in place to attract foreign investment,” Ellyson says. “Yangon [formerly Rangoon] is a hot area right now because it’s a port city with low labor costs and some infrastructure. It’s a fascinating place.”

Foreign direct investment helped along by political stability is already attracting Chinese-owned textile manufacturing in Myanmar. “It’s actually more industrial — think Ikea-type — cut-and-sew products,” says Sweeney. “The next progression is that you would see some simple injection molding pop up in the factories to make the eyelets and the buckles. They’ll start to grow the supply chain that way. Maybe eventually they’ll get the fabric woven there, as you’ve seen in Vietnam now. That’s the natural progression.”

“Myanmar is probably in the top three countries we’ll look at next,” says Ellyson.

China is the investment template. “A lot of countries, like Vietnam, look at what China’s done,” says Ellyson. “They’re saying, ‘We can do that, and probably better. We can protect our environment, our workers, and hold onto our communist rule of law.’ They recognize the things China did very well, like keeping things stable for 20-something years. If the currency’s not moving much, and there’s no instability, things are comfortable. It becomes a nice place to invest. Vietnam looks at China and thinks, ‘We’ll follow some of the same guidelines,’ and you’ll see some of the other Southeast Asian countries doing that too.”

Vietnam gets high marks from East West’s leaders. “We moved to Vietnam originally for rubber and plasticized or flexible plastics, which used rubber by-products in them,” says Sweeney. “The draw for Vietnam was availability and cost competitiveness of those raw materials.”

They say Indonesia’s supply chain is probably a bit stronger than what’s available in Vietnam, but from a labor, management and infrastructure standpoint, they’re relatively equal. “We compete against suppliers out of Indonesia, and I don’t think we’ve ever lost business due to not being competitive with an Indonesian supplier,” says Sweeney.

Brunei and Singapore, while incredibly wealthy, aren’t manufacturing centers. Brunei finds itself dealing with outcomes that occur with a one-dimensional, oil-based economy, whereas “Singapore is like Hong Kong,” says Ellyson. “It’s where you park your money.”

Despite having higher labor costs than Vietnam, Thailand is a duty-free country, making it an attractive place for investment. Unfortunately, Thailand’s political situation is a decided minus. “It’s a great place, but they have a coup every three or four years that throws things around,” Ellyson says.

Consider the Following

Political stability is the number one criterion to look at before investing in Southeast Asia. “It’s got to be when you’re putting capital at risk,” Sweeney says. That includes deal-breaker issues such as transparency and corruption. “We refuse to take part in anything like that at all,” he adds. “We’re transparent to our customers and we expect our suppliers to be transparent to us. We aren’t going to do business where corruption is part of the day-to-day business mode.”

Ellyson ticks off his checklist: “Number one, political stability, followed by stable currency, taxes and regulation, technical know-how, supply chain strength, duties — both import and export, freight costs, labor costs and work ethic.”

Sweeney chimes in. “Availability and cost competitiveness of raw materials,” he adds. “And infrastructure — being able to move products around. Is there a port? Roads? Reliable power?”

The cost of labor and skill level of the workforce remains an issue in emerging economies. Initially, East West brought on ex-pats to use as managers, eventually identifying and training local management.

“Tax incentives are another big one,” Ellyson adds. “It’s also one of the biggest issues the US has. We’re the highest taxed country in the world trying to build a manufacturing base. You pay 7.5 percent corporate tax in Vietnam. If we were to set up here it would be something like 47 percent. It doesn’t make sense.”

Trade, Community and China

2016 Ease of Doing Business Ranking

| 1 | Singapore |

| 18 | Malaysia |

| 49 | Thailand |

| 84 | Brunei |

| 90 | Vietnam |

| 103 | Philippines |

| 109 | Indonesia |

| 127 | Cambodia |

| 134 | Laos |

| 167 | Myanmar |

| 173 | Timor-Leste |

To the question of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), neither believes the free trade agreement will be finished in this contentious election year, but they are ardent supporters. “We’re a free trade company, so anything that frees up trade, we support,” Sweeney says. “Selfishly, it gives us a competitive advantage because a lot of what we do is in Vietnam, and average duty rates in Vietnam are three percent. A three percent cost advantage helps our customers and helps us.”

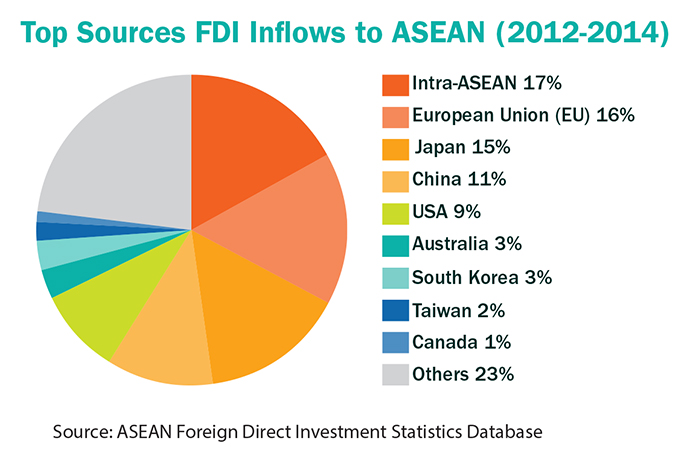

Can the ASEAN nations achieve economic integration through the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), established in 2015, given the large disparities in development throughout the region? “The ASEAN Community is like the EU model,” says Sweeney. “And do you gain enough in scale to make up for what you might not have in alignment? I think they’ll have a larger alignment problem than the countries in the EU did because of security.”

But security is also a driver for the TPP among Southeast Asian nations. “Look at the power struggles they have there, but all of them have one thing in common,” says Ellyson. “They’re all afraid of China. That’s why the TPP came about. It was all because of what China was doing on the rare earth metals. Japan said we need to band together and stay competitive against this China machine. I think that’s not going away. If anything, the fear is building.”