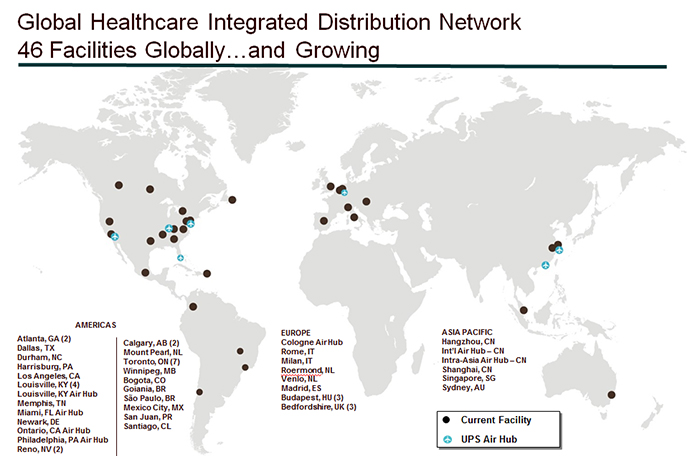

Since 2000, the UPS healthcare logistics network has grown from 10 fully-compliant healthcare-dedicated facilities in North America to 46 facilities in strategic locations around the world employing 5,000 people and dealing daily with hundreds of licensing, customs and other protocols in trying to speed critical medicines, devices and equipment to the patients who need them.

The network is growing fast, and will close in on 50 locations soon: UPS on April 3 held a ribbon-cutting ceremony in the state of Mexico, celebrating the addition of three healthcare-dedicated facilities to address high-growth medical device and pharmaceutical consumption markets throughout Latin America. Over the coming months, UPS will open and expand new facilities near Mexico City, Mexico; Sao Paulo, Brazil; and Santiago, Chile.

With these expansions, UPS’s network in the region reaches nearly 70 percent of the total healthcare consumption and manufacturing markets in Latin America. The moves also mesh well with the US Department of Commerce-led push to increase trade with Mexico and the 10 other Latin American economies with which the U.S. has free trade agreements.

“UPS is excited about the new business opportunities the Look South initiative will bring for businesses, particularly small and medium enterprises, to expand into these growing markets,” said Romaine Seguin, president of UPS Americas Region, in January.

“Latin America represents a strong growth opportunity for healthcare companies and providers who rely on UPS’s network of dedicated facilities, air freight, and safety and compliance expertise to support their business goals,” John Menna, appointed UPS vice president, Global Healthcare Strategy in February, said the grand opening early this month in Mexico City. “These facilities offer greater access to the best-in-class logistics solutions for pharmaceutical, biotech and medical device companies serving Latin America, giving global healthcare customers the confidence they need.”

The southern focus includes two acquisitions in Costa Rica last year. But the company’s looking in other compass directions too, such as north: In January UPS Canada, whose healthcare logistics network spans 11 facilities, official opened a new 200,000-sq.-ft. facility at its now-600,000-sq.-ft. campus in Burlington, Ont. The facility is one of several North American expansions including facilities in Louisville, Ky.; Mira Loma, Calif.; Atlanta, Ga. (Suwanee); and Reno, Nev. Often the growth comes as single-client facilities evolve into multi-client facilities, helping all concerned in terms of optimizing capacity utilization.

There’s growth to the east as well. Strategic acquisitions during the past three years have included healthcare logistics companies Pieffe (Italy), CEMELOG (Hungary) and, most recently, Polar Speed (UK) in February. And one facility in the company’s new complex at Logistics City in Dubai will be dedicated to healthcare as well. At the same time, the healthcare logistics arm of UPS has expanded its network of field stocking locations (FSLs, which serve more than just healthcare) in Africa and the Middle East to 25, opening them at the rate of one per month over the past year. UPS has more than 900 FSLs worldwide.

The Network Comes First

Menna, a 28-year UPS veteran, and Robin Hooker, a 26-year UPS employee and former director of global healthcare logistics strategy who now directs the company’s healthcare sector marketing, met with Site Selection this month at UPS world headquarters in Alpharetta, Ga.

Asked about the Latin America site selections, Menna said the UPS site selection team usually includes personnel from the healthcare strategy group; plant engineering, real estate, the business unit that will run the facility, finance and tax departments and public affairs. The first facility siting litmus test is good connectivity to the global UPS transportation network, whether by road, air, ocean or all three.

“In most cases it will definitely be our air network, and to some degree our road network, in order to provide good access to the healthcare product consumption based within that country,” said Menna. “Then we look at things like infrastructure, electrical grid, water, sewer and sanitation. We look at crime areas, and we look at tax incentives or tax implications of locations.”

Hooker pointed out that both Brazil and Mexico are among the top 20 markets for importers according to the most recent edition of the Biopharma Cold Chain Sourcebook from Pharmaceutical Commerce. Last April the publisher estimated the current market for cold-chain logistics services to be worth $7.5 billion, rising to $9.3 billion in 2017.

The growth is dynamic, but it’s also inextricable from the web of trade and customs policy companies have to navigate daily.

“It’s an extremely highly regulated space,” Menna says. “When it comes to licensing, operational authority, flights in and out — there is a huge amount of trade policy within healthcare. Fortunately we have a pretty strong public affairs group at UPS who work very closely with local authorities, and help them understand the importance of providing access for their population base to some of the most advanced medicines and therapies. It’s in their best interest to bring down regulatory barriers, or at least make them manageable.”

Hooker points to Brazil as a key example of a market corporate clients want to access, but where the chief regulatory body just updated guidelines last year. “The key factor is how to access it in an agile manner, and without growing your own regulatory body each time you access a country,” he said.

That’s where the UPS model comes into play. But there are times when the company itself has to overcome puzzling regulatory situations. One of those big South American countries, in fact, was treating one of the company’s highly specialized shipping containers as a product rather than a container for product, and overcharging accordingly. Thankfully, says Hooker, the container is engineered to such a degree that it has “a pretty lengthy hold time. The beauty of that container is it’s monitored by our control towers. If there’s a hold, we know about it, and have a team staffed to move quickly and address it. We work collaboratively with our customs agents to get them familiar with the product and the container.”

“We do a lot of education around these new types of products with local authorities who are putting in regulations or taxing,” adds Menna. “We have public affairs people who can go into any country and work with regulatory authorities to work out these issues.”

Special Treatment

While it might seem natural to dovetail the facility footprint with the overall facility network of UPS, healthcare is the area where UPS does that the least, due to the high levels of security, temperature control and specially validated IT systems required for healthcare. “It’s such a specialized type of operation,” says Menna. “We try to make it tie in to the rest of our business. Some facilities have healthcare products, then a demising wall, then other products.”

The most typical space sharing occurs between healthcare and high-tech electronics, such as at the company’s Worldport hub in Louisville, where such sensitive items as skin grafts for diabetic ulcer surgery are stored and shipped.

“By having our healthcare facility located near our Worldport facility, we can take orders up to 12 at night, and pick, pack and ship them to other countries the next morning,” says Menna. Hooker notes that area bio clusters near UPS air hubs would do well to focus on the lab test niche, because of the specific ability of such hubs to turn around test results fast.

In a recent talk at the MODEX annual logistics conference, Hooker described the precision and drama such activity can encompass.

“We start a stopwatch when the freezer is opened,” he said. “If not closed within the proper time, it has to stay shut for several hours.”

And those hours can mean a lot, he said, citing the experience of a California manufacturer that distributed materials for diabetic foot ulcer surgeries out of that state, but had created a secondary distribution node at UPS Worldport as a risk mitigation measure.

“One summer there was a brownout that impacted the Los Angeles airport,” Hooker related. Thanks to the backup plan, “It was a simple matter of rerouting the distribution orders. They just toggled all the orders over to Louisville, and we fulfilled the order process seamlessly.”

Not that it didn’t require a little extra effort.

“We had to call in our work force that had already been dismissed,” said Hooker. “But because Louisville is the jumping-off point for our air network, we could process late into the night and get that air volume out on flights by 2 a.m. The patients didn’t know the difference.”

Sometimes the difference in product directly affects a location choice, says Menna, reiterating the chief requirement of tying into the UPS transport network.

“In Europe, our major air hub is in Cologne, Germany,” he says, “and we wanted to have good connectivity. We located our healthcare main campus in the Netherlands, in Roermond, just over the border from Germany. It’s a fairly short drive from Cologne, and it was done primarily for tax reasons — there is a different scheme for healthcare products in the Netherlands. And we still maintain the tight connection with our air hub.”

Epidemics, Brands and Security

Among the healthcare division’s newest facilities is a site in Hangzhou, China, where diabetes growth is on a stark upward path, part of what is officially characterized globally as an epidemic. Hooker says the division has encounterd a lot of opportunities to collaborate with clients working out their own Asia Pacific and India growth strategies. That includes R&D.

“They all seem to have a proactive strategy from an R&D perspective,” says Hooker. “It bodes well with the government agencies.” At the same time, as the economy gets stronger, “there is a brand issue China faces related to localized manufacturing — it’s quality. The affluent are wanting to purchase healthcare products that actually are manufactured outside the country.”

However, despite some recent headwinds for major brands involving compliance and ethics issues, “I think we’ll continue to see localized manufacturing and R&D” in China, Hooker says.

Hooker has been closely involved in the company’s Pain in the (Supply) Chain Healthcare Survey, which not only provides valuable intelligence to the marketplace as a whole, but informs UPS strategy as well. In its most recent iteration, regulatory compliance was the top issue of concern for respondents globally, at 63 percent, followed by product security (53 percent), which just took over the No. 2 spot from supply chain costs (51 percent). Product damage/spoilage was a concern to 43 percent of respondents, followed by access to global markets and new customer bases, at 37 percent. But nearly half of respondents, 47 percent, said regulatory compliance was the chief barrier to that global expansion.

The top product security challenge is counterfeiter sophistication, which Hooker says is growing faster than countermeasures.

“The agility in the counterfeit marketplace is a model we could all benefit from,” he says ruefully. However, he adds, “Some of the best models out there are collaborations with Interpol and with private enterprise, and sting operations capturing the front end of the demand side — the Internet website creating the demand and channel. A lot of these medications don’t even have the API [active pharmaceutical ingredient] as part of the formula.”

Menna says facility measures such as fencing, double-gate entry procedures, armed security guards, cameras and vaults help. “We recognize the products we store in these facilities are very valuable and expensive,” he says, “and make sure we have security measures in place to make our clients comfortable.”

UPS is collaborating with all partners on such factors as visibility of shipments, collating information and tracking the pedigree of drugs so there’s less opportunity for gray markets to form. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 percent of medicines in the developed world are counterfeit, but in emerging markets it can be as high as 30 percent, Hooker says.

The company’s increasing facility footprint in those very markets may thus go a long way toward not only reaching those markets’ growing consumer and patient populations, but helping protect them at the same time.