In what, by any measure, has been a rough year, Louisville’s arguably has been rougher than most.

Nearly concurrent with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic nationwide, Louisville was an early flash point in the wave of anti-racism demonstrations and social unrest that was to sweep the country months later, after Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old unarmed black medical worker, was fatally shot in March in her apartment during the botched execution of a no-knock search warrant by the city’s police department.

By May, when the city would usually be awash in Kentucky Derby festivities and their $400 million economic impact, the Derby had been moved to September, investigations continued by local and state authorities as well as the FBI, the police chief resigned and reforms were being discussed and re-discussed. Then George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police in Minnesota sparked larger and more fervent protests that were marred by vandalism and shootings. Mayor Greg Fischer instituted a dusk-to-dawn curfew and the National Guard was called in by Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear.

Summer saw daily protests, a call for a no-confidence vote on Mayor Fischer, clashes between militia groups and continuing unrest, with hundreds gathering outside Churchill Downs in September in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to shut down the 146th running of that postponed Kentucky Derby.

“It was surreal to have a Derby in September, without people,” says Mary Ellen Wiederwohl, chief of Louisville Forward, who was justifiably somewhere other than Churchill Downs that day. “It’s an amazing tradition I’ve loved, but I took several steps back from it, and spent that week listening to the folks in our streets talking to us about why we can provide economic opportunity for all. It was a moment of deep reflection and contemplation, because what we were really focused on that week was the protests in our streets and the fight for racial justice.”

But even as a community works through such mammoth issues, companies continue to do business and grow operations. And when Site Selection examined corporate facility project data on a cumulative and per-capita basis over an 18-month period extending from 2019 into this past summer, the Louisville metro area came out on top. Greater Cincinnati was second, followed by Owensboro and Paducah, Kentucky.

Strong Clusters, Robust Programs

Even since the beginning of 2020, the Louisville region has tallied 30 located projects, adding 1,253 jobs and representing $253.2 million in new investment.

“In some ways, it is a surprise because of the year we’re in, and the challenges unlike anyone who’s alive has ever seen,” Wiederwohl says. “But if you take a step back and analyze it intellectually, you can see we’re doing well because of the ongoing strength of the local economy. When COVID and the lockdown hit in mid-March, we were concerned like everyone that things would come to a screeching halt or hit a pause. A lot of folks said, ‘We’re just going to wait and we’ll return next quarter,’ but a lot of things picked back up faster than we thought. This country is still making things and this country is really buying things through e-commerce. The other real winner for us is the technology space.”

That includes software group Bastian Solutions, a firm whose niche grew out of a background in logistics. “Bastian had a project of over 140 jobs earlier this year, and is looking at maybe another expansion,” says Wiederwohl. Eurofins, a high-end logistics, genetics testing and food testing company that located in Louisville several years ago, is also going forward with an expansion. The city’s target sector of aging care is still attracting interest and projects, including Aging 2.0’s move of its headquarters to the city, where they will be part of the Louisville Health Care Council, an organization formed to promote and attract new opportunities.

Being a great river town means still has strength in advanced manufacturing and logistics, including surging interest in cold storage. Preparing for more is why phase five of the city’s Riverport complex redevelopment is underway, with 160 site-ready acres. That site is not far from the UPS Worldport, near which UPS is investing $750 million in a new aircraft maintenance facility as the delivery giant prepares to be a big part of vaccine distribution in the coming year.

UPS earlier this year celebrated more than 20 years of its unique Metro College workforce training and higher education partnership whereby students have their tuition covered and attend specially scheduled classes while also working night shifts at UPS. The company signed a seven-year extension with partners at the University of Louisville, the city and Jefferson Community and Technical College.

“It’s amazing to think it’s 20 years old, and still the model to be admired and replicated,” Wiederwohl says. “It is a really exciting partnership because everybody is at the table and has skin in the game,” including the latest tweak to make sure students are better matched with high-demand career fields and apprenticeships.

According to UPS, more than 20,000 students have participated in the program since 1998. In all, 5,942 Metro College students have earned 10,050 degrees and certifications. Students from more than 100 Kentucky counties have participated. The program has improved UPS employee retention by 80%.

Other, newer programs directly address talent development while also striking at the income inequality lies beneath Louisville’s racial and socio-economic strife.

In 2019, Louisville Forward launched a TechWorks initiative with the goal of quintupling projected tech talent growth. And more recently, just before the pandemic struck, it launched its Future of Work Reskilling Initiative in partnership with Microsoft, with the goal of injecting new skills in AI and data science into the area’s manufacturing, health care and other sectors. Even with the shutdown, the program received 4,455 expressions of interest, 739 badges have been awarded, and 150 people are enrolled in an upskilling academy that is partnered with Humana. Of those who filled out the survey as part of the initiative, 32% self-identified as minorities, 20% were black and 57.8% were female.

Lower Costs, Steady Talent

In “Strategic Cost Considerations for Corporate Employers,” the third report in a series on evolving location strategies in the COVID-19 era from CBRE’s Labor Analytics Group, the authors note that in addition to evolving workplace strategies involving remote work, “employers are focusing on cost containment, driven by falling revenues for many industries. As a result, many companies are rationalizing their portfolios and modifying their location strategies to maximize cost savings.”

Ohio River corridor markets are positioned to take advantage of those moves.

“Before the pandemic hit, several areas in the Midwest continued to gain attention of employers for lower-cost and lower demand labor environments, including metros in the Ohio River Valley area,” says Kevin Major, CBRE senior director, Client Strategy and Consulting.

Reducing a real estate footprint is a common method for managing costs, CBRE says, but moving jobs to lower-cost locations “creates a much greater return on investment (ROI) over the long term. Assuming a utilization rate of one person per 125 sq. ft., they say, “Consider this: Just a $1/hr. savings in labor costs is the equivalent of $16.64 per sq. ft. in real estate costs.”

Housing matters too. Evaluating to what degree a $1,200 stimulus check covers the average monthly rent of a two-bedroom apartment, the CBRE team found a swath of affordability throughout the Midwest, including Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Louisville. Pittsburgh (at 13.5%) is No. 1 and Cincinnati (at 15.6%) is No. 9 when it comes to lowest percentage of income spent on housing among cities larger than 750,000 in population.

Louisville’s Labor Advantage

The CBRE team’s map of expanding and emerging markets where companies and communities alike could take advantage of this relocation trend only includes two cities in the Ohio River Valley region: Pittsburgh and Columbus (the latter is not considered in Site Selection’s Ohio River Corridor rankings, which only evaluate metros in counties abutting the river itself). I asked Major where Cincinnati and Louisville fit into the mix.

“While Louisville and Cincinnati have gained more interest from employers pre-COVID, Columbus and Pittsburgh were gaining more attention for tech talent as employers looked outside traditional tech hubs like the Pacific Coast, New York, D.C. and Austin,” he says. “Pittsburgh has drawn tech-driven companies like Uber to open offices while Columbus has been home to many corporate HQs in which many house tech functions.”

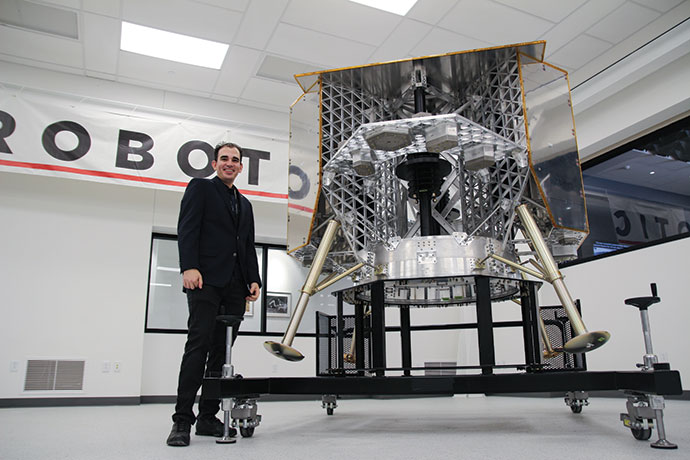

Pittsburgh continues to draw tech investment, much of it due to homegrown connections at Carnegie Mellon University. In October the area celebrated along with U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross the grand opening of the new space robotics headquarters and lunar operations facility of Astrobotic, a company spun out of the university.

“I like to say we’re a 13-year overnight success story,” said Astrobotic CEO John Thornton. “In the past 18 months, we grew from a staff of 18 to more than 100 employees, with two funded lander missions and a rover mission to the Moon, and multiple contracts to develop exciting new space technologies. It’s still surreal.”

Louisville and Cincinnati have lagged behind in attention from tech employers when compared to Columbus and Pittsburgh, says Major. But a shift might be in the cards.

“As many organizations deal with tighter budgets in the near term due to the impact of COVID, one of the largest areas an organization can cut costs is through labor,” Major says. “This is where Louisville has a notable advantage. The median household income for Louisville is more than $3,000 a year lower than Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis. The average salary of a software engineer with five years’ experience in Louisville is approximately $8,580 less than the average software developer salary in Columbus. The Kentucky market also has a relatively low cost of living. Because of this, Louisville could be on the radar for various corporate operations and support hubs as organizations look to cut costs.”

That said, Louisville may not draw as much attention as some other regional metros due to its size, as local employment is roughly 638,000 less than Pittsburgh, he points out. “This is where Cincinnati may have an advantage. Its employment is similar to Columbus in size but has not recognized as much growth or attention as Columbus has in recent years. For employers looking to take advantage of a lower cost market in the Midwest that has not been ‘on the radar’ like Columbus, Cincinnati could offer a less competitive environment less prone to wage pressures once the local and national economies gain steam again.”

Among the companies landing in the Cincinnati region is AddUp, Inc., the U.S. subsidiary of AddUp, a global manufacturer of metal 3D printing equipment and supplier of 3D printed parts, which announced in October establish its North American headquarters in Blue Ash, Ohio, at the current location of AddUp’s other U.S. subsidiary, BeAM, Inc. The two companies will form one operating unit, and provide an Ohio bookend to America Makes, the U.S. Department of Defense’s designated Manufacturing Innovation Institute for Additive Manufacturing in Youngstown.

Test Site for Remote Work, Equity

The “emerging” markets of Louisville and Cincinnati could emerge as test markets for new working strategies.

“While it is too early to tell how work-from-home will be adopted over the long term, it may allow the flexibility for organizations to test lower-cost markets in the Midwest like Louisville and Cincinnati for talent by hiring talent virtually,” Major says. “An organization can hire in the low-cost market without committing to a large headcount. If the organization finds success it may focus recruiting in the market and entertain a physical site should it be needed/desired.”

Wiederwohl says that is exactly what Louisville aims to do.

“Cost competitiveness is a calling card for Louisville,” she says. “In terms of talent, our residential real estate market is very strong. We’re having exciting conversations with site selectors working on projects with tech companies, who are exploring new models for how to do business, such as a hybrid model where you’re working at home, but you would convene in a city monthly or quarterly. I think we are going to see interesting innovations in this area, and I believe Louisville will benefit from however this shakes out.”

In the meantime, city and company leaders deal with the dual realities of expanding business and expanding the definition of inclusive success. Wiederwohl is on the racism and economic development committee recently formed by the International Economic Development Council.

“It’s been gratifying to sit on those calls, have a moment of self-examination and recognize that the field of economic development is a part of structural racism,” she says, tracing all the way back to real estate redlining, discriminatory lending practices and urban renewal programs that didn’t renew so much as reinforce. It’s a force that contributed to the struggles of Louisville’s West End, and continues even as the area has seen an infusion of more than $1 billion of investment since 2014. She says it’s time to think and act deeply, particularly with regard to incentives, so as not to reinforce that systemic, built-in prejudice.

“Look at the protests in our streets,” she says. “In some ways I can’t believe it took this long. But you are also seeing a generational movement, and it’s a financial movement, with lack of mobility again disproportionately affecting black and brown people.

“Louisville has been very much in the spotlight,” she says. “We’re not going to shirk that. The good news is the economy continues to bring us new opportunities. We’re going to make sure Louisville is better, stronger and more equitable for the future.”