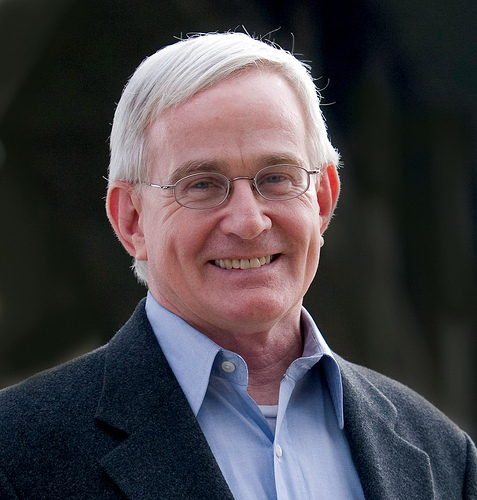

Famed urban renewal leader Tom Murphy has seen firsthand what can happen when civic leaders accept less than the best and highest use of land in a city: "I go to a lot of cities where there’s this disease in the water called the ‘it’ll do disease,’" he says.

The former three-term mayor of Pittsburgh should know. When he took over as mayor of the Steel City in January 1994, urban decay had already settled in amidst the wake of the demise of the once-vaunted steel industry. Doing anything less than the best at urban revitalization was unacceptable, he said.

For an hour at the Metro Atlanta Redevelopment Summit on October 25 in Duluth in Gwinnett County, Georgia, Murphy detailed his prescription for urban renewal.

Calling Atlanta "one of the great cities of America," but also one "facing great challenges," Murphy implored his audience of civic and business leaders to not just embrace the challenge of urban revitalization, but to "kick down the door."

As a senior resident fellow and chair for urban development at the Urban Land Institute, Murphy frequently speaks and writes about the need for cities to embrace change and partnerships to conquer systemic problems of poverty, disenfranchisement, alienation, racism and lack of economic inclusion.

He cites as an example the story of Horatio Nelson Jackson, who in 1903 defied naysayers and became the first person to drive an automobile across the country. "He did it at a time when America had 150 miles of paved roads, and he did it in 63 days," says Murphy. "By 1923, America had 10 million cars. Society changed completely."

Coping with rapid change means meeting six converging forces head on, he says: globalization, environmentalism, technological innovation, demographics, talent and financing the future.

"We’ve had 64 500-year natural events this year," Murphy notes. "Things are changing, and they’re changing more quickly than ever before."

Learning Lessons from Pittsburgh

The key is intentionality, he says. "Look at the communities that get it: Denver and Loveland, Colorado; Greenville, South Carolina; Cincinnati, Ohio; Charleston, South Carolina; and Bethesda, Maryland," he notes. "They get it because they understand the importance of money, land control, sophisticated deal-making capacity, vision and leadership."

Case in point: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. "After the steel mills closed down, we lost 500,000 people from 1970 to 1990," Murphy says. "When I became mayor in 1994, we had just been managing decline. South Side Works was a steel mill. My father worked there for 51 years. When it closed down, we had to reimagine Pittsburgh."

The turnaround began when the president of Carnegie Mellon University told Murphy that the school could become an economic engine for urban renewal. "The problem at the time was that we had no entrepreneurial culture," says Murphy. "People belonged to unions or other large organizations that controlled everything. They weren’t accustomed to innovation."

That changed under Murphy. By the time he left office in December 2005, the city had seen more than $4.5 billion in economic development, including a billion dollars to fund construction of new stadiums for the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Pittsburgh Pirates at the convergence of the three rivers in town.

Murphy oversaw development of a new convention center that is the largest certified green building in the United States. Moreover, he directed strategic partnerships that transformed more than 1,000 acres of blighted, abandoned industrial sites into new commercial, residential, retail and public uses, and he spearheaded the development of more than 25 miles of new riverfront trails and parks.

"South Side Works was an operating steel mill for countless decades. Now it has a Cheesecake Factory and other successful restaurants and retailers there," Murphy says. "That urban redevelopment project cost $650 million, including $301 million in private investment and $128 million in public investment. Putting a new Home Depot store in East Liberty was an $11.35-million development. It was one of the first urban Home Depot stores in the country, and today it ranks as the best-selling Home Depot in all of Pittsburgh. That led to a Whole Foods being established in East Liberty, as well as hundreds of units of new housing."

Murphy: Stop Waiting to ‘Kick the Door Down’

Examples of turnaround abound in Pittsburgh. An abandoned Nabisco factory became the home of Google. Downtown Pittsburgh and its riverfront were revitalized. Some 7 million people a year now visit a part of town that used to be the worst place in the city.

"One of the smartest things we ever did was pass a half-cent regional sales tax to pay for regional amenities," says Murphy. "Because of that tax, you can now hop on a bicycle and ride it on a trail all the way to Washington, D.C., and never have to get on a public road."

“When I became mayor in 1994, we had just been managing decline. South Side Works was a steel mill. My father worked there for 51 years. When it closed down, we had to reimagine Pittsburgh.”

The success continues, he notes. Pittsburgh annually produces 35 to 45 startups that collectively rake in $250 million in venture capital. University of Pittsburgh accounts for $861 million annually in R&D expenditures, while CMU tallies $242 million.

"We have 200 driverless cars on the streets of Pittsburgh now," Murphy adds. "Are you, like Pittsburgh, willing to embrace the future, or will you settle for managing decline? You can either continue to manage decline or reach for the future? I hope you kick the door down."