Remember those trade route maps you studied in school, with the dotted lines showing where the ships crossed oceans and came into port centuries ago? Today there are other lines meandering below those vessels that are their own indicator of commerce: the subsea cables carrying terabits of data.

Some of the locations where those cables crawl ashore from the murky deep are landing their share of data centers, as the new lines increase the connectivity and therefore the attractiveness of the communities where they land.

The Virginia Economic Development Partnership recently highlighted subsea cables in its Virginia Economic Review publication, where Sean Ballie, chief of staff at QTS Realty Trust, said, “Just a few years ago you rarely heard talk about subsea cables when you were talking about data center infrastructure. Today, virtually every data center is making interconnection with subsea cables a priority to support data-driven global business.”

That’s certainly the case in Virginia, where the northern Virginia region has more data center inventory than the sixth- through 15th-largest markets combined, says a report from the Northern Virginia Technology Council. In 2018, the data center industry in Northern Virginia provided more than 10,500 full-time-equivalent jobs paying more than $1.6 billion in associated wages and salaries and created more than $3.5 billion in economic output. The market has added 4.5 million sq. ft. (418,050 sq. m.) of new data center space since 2018. Data centers contribute more than $300 million annually in local tax revenue in Loudoun County alone.

“These data centers are the backbone of Loudoun’s economic success, providing the resources for full-day kindergarten, the strength of our public education system, and more than $1.2 billion in transit improvements,” Loudoun County Chair Phyllis J. Randall said.

But facility development occurs in other parts of the state too. In October 2017, for example, the Corporate Landing Business Park in Virginia Beach was approved as a Dominion Energy Certified Data Center Park. It took advantage of the only transatlantic cable landing in the center of the East Coast — able to send 160 terabits of data per second all the way from Bilbao, Spain — as well as the Globalinx carrier hotel.

In addition to data center tax rates significantly lower than such leading data center counties as Loudoun and Fairfax, Virginia Beach also is creating a suite of Technology Zone incentives built around the cable and data center nexus. The area now hosts the BRUSA and MAREA cable systems (landed in 2018), with the Google-backed DUNANT cable (able to deliver 250 terabits a second) due to arrive this year.

Traffic Jams

The Global Data Center Market Comparison report published by Cushman & Wakefield’s Data Center Advisory Group in January compares and ranks 38 markets on the surface of the earth. But it notes that the underwater web that facilitates the digital web merits close attention going forward.

“Sixty new undersea cables either completed in 2019 or are coming online in 2020, the highest two-year total in history,” the report says. “The continued need for greater bandwidth is expected to multiply over the next decade, as more countries gain internet users and companies develop new applications.”

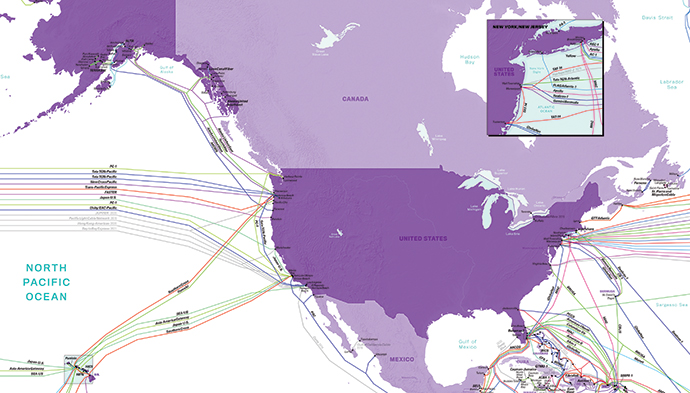

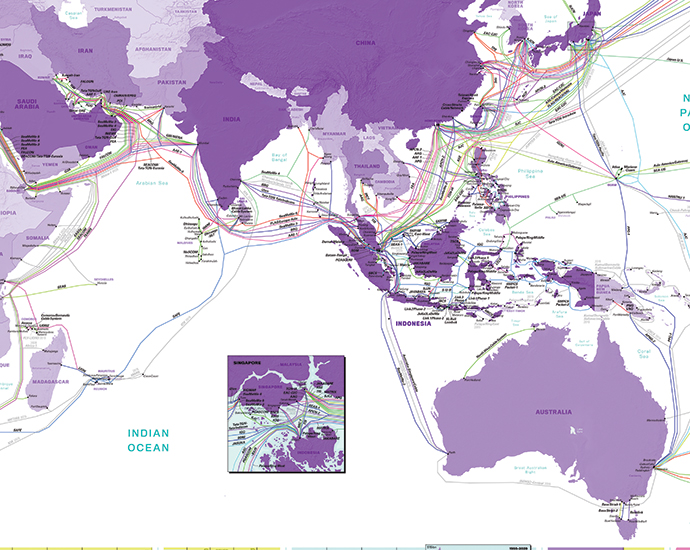

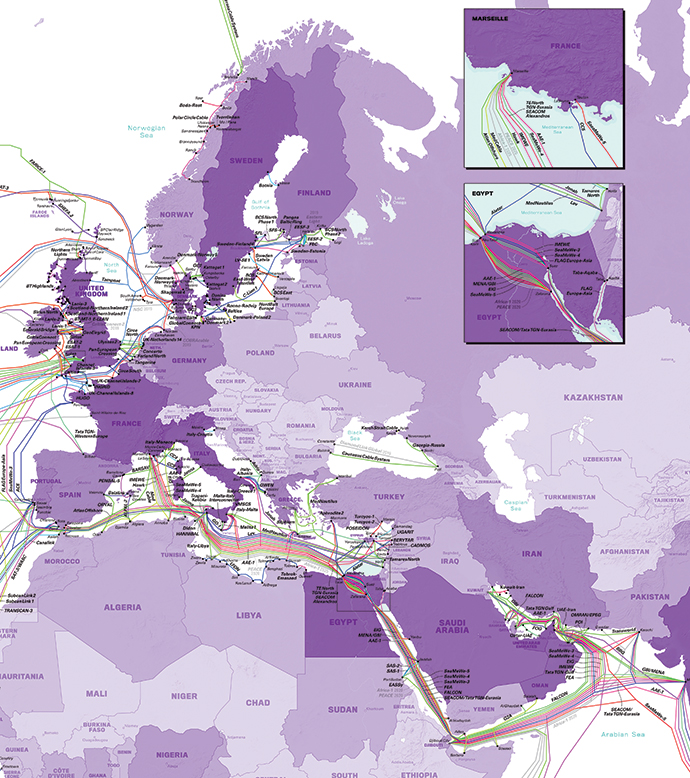

As of early 2019, reports TeleGeography, there were 378 submarine cables in service around the world. The organization, backed by sponsors Huawei Marine and data center giant Equinix, maintains a complete interactive map of all of those cables and their capacities, users and landing points at submarinecablemap.com. Excerpts of this incredibly detailed tool appear in these pages. As of 2019, says TeleGeography, around 1.2 million kilometers (745,804 miles) of submarine cables are in service globally, ranging from the relatively short CeltixConnect cable between Ireland and the UK to the 20,000-km. (12,430-mile) Asia America Gateway cable. The company’s Data Center Research Service includes an interactive map depicting more than 4,000 active data centers.

“Undersea cables and a strong business climate have developers building up,” the Cushman & Wakefield report says of Singapore, ranked No. 6 among its 38 top performers. “Dense fiber and a large, densely packed population with access to many undersea cables,” it says of No. 8 Los Angeles.

Singapore might not stay at No. 6 for long.

“Singapore just put a moratorium on data center development, just like Amsterdam did a couple weeks previous,” says TeleGeography Senior Manager Jonathan Hjembo, who heads the company’s global data center and internet infrastructure research. “It’s about power usage. We don’t know how it’s going to affect development in the pipeline right now. It’s troubling in the short term. It sounds like Amsterdam will work around it and work with industry to figure something out.”

Turning Point in Asia

“I see data center operators, especially in Southeast Asia, making significant moves into markets traditionally considered too difficult,” Hjembo adds. “It’s an inflection point. They’re saying, ‘The indicators are there. We know the traffic is there. If we do this right, we can get around the problems of backhaul. And we need alternatives because existing hubs are volatile, and expensive,’ ” Hong Kong being a prime example.

Hjembo says a lot of conversations at a conference he just attended in Hawaii revolved around what’s going on in Southeast Asia. Investment is happening “even in places that may not seem quite ready, places that interconnection players have been circling for a long time,” including Bangkok, Jakarta and “Manila in particular. There is a lot of chatter about what could be done there, and there are major cables popping into the Philippines now.”

Other players such as ST Telemedia from Singapore are pulling the trigger on internet exchange points deeper into India and mainland China. There is a flurry of activity in South Korea now too, Hjembo says, where Equinix has just invested and Google has just deployed a new cloud region.

“These are all locations with major challenges that can’t be overlooked, but people are finding ways around the challenges, or think the risk is worth it because all of these places have tremendous local demand,” he says. “They’re densely populated, with lots of economic activity and huge demand for cloud and content applications. Part of it is we can’t just rely on Hong Kong and Singapore. It has to extend deeper, and end user applications are just going to get more bandwidth-intensive and more localized.

“You can’t just backhaul everything to the biggest nodes,” he says. “The potential is there, the traffic is there, the appetite for peering is there. It’s an opportunity to bypass some of the encumbrances.”

Heavy Hitters

Hjembo also oversees internet infrastructure research closely tracking the activity tied into the globe’s more than 240 internet exchange points. (See TeleGeography’s map of those assets at internetexchangemap.com.) He says sometimes the emphasis on the real estate play of data centers is so heavy, people forget that network access is the point. At TeleGeography, they watch network, interconnection nodes and data centers simultaneously.

“Where you see development in one of those verticals, you’ll see it in another,” he says. As he and his team track internet route development, they’ve seen a “major increase in deployment of routers in nodes that haven’t been on the radar. We haven’t seen traffic to those places, but we’ll see data centers following suit.”

Some of the biggest enterprise data center developers — Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon — now are also major investors in new submarine cables. “The amount of capacity deployed by private network operators — like these content providers — has outpaced internet backbone operators in recent years,” TeleGeography reports. “Faced with the prospect of ongoing massive bandwidth growth, owning new submarine cables makes sense for these companies.”

“Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon are anomalies,” Hjembo says. “Even some of the biggest cloud users’ capabilities pale in comparison to what those guys are doing in terms of investing directly in international networks. It’s a strange anomaly, because it’s an anomaly that’s driving the market right now. A handful of players are driving how subsea routes are developing. And carriers can’t do much development on their own without partnering with one of those entities. The network play itself is now less a PoP-to-PoP thing and more of a data center play, and it’s specifically for them. They have their own strategies for where and how they’re going to develop their data centers, from huge to small, from hyperscale to edge nodes in the colocation facilities.”

As for the real estate where submarine cables land, Hjembo says it’s basically a transition from the wet plant of the heavily insulated fiber-optic line to a dry plant at the cable landing station (CLS), as the cable transitions to terrestrial backhaul, whether provided by the cable consortium partner, “or other carriers coming in and popping that CLS,” he says. In Virginia Beach, Telxius has constructed a large facility, with most of the backhaul taking “the express route to Ashburn,” the city in northern Virginia with perhaps the highest concentration of data center space in the world. Telxius has a data center in Virginia Beach, which Hjembo says makes a lot of sense as the company has a stake in both cables landing there, and in fostering more direct Latin America-Spain business.

CLSs, PoPs, IXs and Eyeballs

So, is it helpful to be near a landing station with your data center? Maybe, says Hjembo. But it’s not as important as being near demand.

“You have to think of the subsea cable as just a physical part of a global network,” he says. “The real question is, ‘Where are the eyeballs?’ The landing station is just where the wet plant can’t go any further, but you can bet they’re planning that as strategically close as they can to where they ultimately need to go. So the question goes the other way — where are the end users? The location of a landing station can be an intriguing part of that question, especially from a development perspective.

“You want to know where there’s a convergence of high-capacity transoceanic infrastructure,” he continues. “But the demand is not ultimately focused at the cable landing station. Proximity may be important to certain users because they want to be able to quickly express route things out of a location. But for the most part they want to be close to the population centers too. I’ve heard firsthand from one or two operators wrestling with this a little bit,” but ultimately choosing options near to those population centers. That explains why some of the densest landing sites include New York/New Jersey, Porthcurno (on the very southwest tip of the UK, to serve London), and Bude (in Cornwall, also serving London).

But there’s another way of looking at it, he says, by “thinking in terms of where an ecosystem could be established, where you could capture traffic at data centers and create an interconnection node. People look at the subsea routes and say, ‘Is there a point along this route, a point in transit where some of the traffic could be captured and localized?’ Between Europe and Asia, for example, I hear a lot of people asking, ‘Is there a place in the Middle East where we could set up a node and capture some of this traffic?’ One example some consider a success story is Marseille. That’s a situation where you have a data center/internet exchange ecosystem able to capture demand coming from North Africa that would otherwise backhaul to Frankfurt or Paris. A lot of people are chasing that, but it’s not necessarily easy to pull off.”

Skip the Transition

One trend worth noting, says Hjembo, is around 20 submarine cables where the submarine line termination equipment (SLTE) extends all the way into metro-area colocation data centers. A few cables over the past decade have landed directly in colo facilities or carrier hotels in London, New York and Hong Kong, he says.

“Now Equinix and others are landing deals to get subsea cables directly into their buildings. That means rather than having a landing station to transition to terrestrial, the subsea line goes straight to the shore and all the way into the data center, and now they can also split that SLTE among several buildings,” he explains. “They’re doing that in Perth, Australia. That’s something to keep an eye on. That speaks to where the traffic is ultimately going. The location of convergent points of subsea cables matters, but not as much as where it’s ultimately going.”

The submarine fiber industry added an average of 32% capacity annually on major submarine cable routes between 2013 – 2017.

Google last February selected Equinix for its Los Angeles CLS supporting the Curie subsea cable system. The cable is landing directly at the Equinix LA4 International Business Exchange (IBX) data center located in El Segundo, California. The new route is the first subsea cable to Chile in the last 20 years, and just went live. It’s part of a Latin America focus that saw Equinix in January launch three new IBX centers in serving Mexico City and Monterrey.

According to Equinix’s latest Global Interconnection Index, Latin America is estimated to have the strongest regional interconnection bandwidth compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in the world at 63% by 2022. “The top four LATAM metros (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Mexico City) are expected to equate to 77% of overall Latin American interconnection traffic by 2022,” Equinix said in January, “with Mexico City’s interconnection bandwidth growing at a rate of 52%.”