“We need more data.”

It’s the rallying cry of every scientist, researcher, policymaker, baseball general manager of the “Moneyball” school and journalist reporting out an ambitious story.

Ambition for change in community circumstances was at the heart of the Opportunity Zone (OZ) program when it was enacted in December 2017 as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. But change takes time.

Early returns on such programs can be as misleading or inconclusive as early returns on election night. When the real data start to stream in — in OZs’ case, after several years of regulation promulgation and then actual investment across the 8,000 designated high-poverty zones — a clearer picture emerges.

That picture is at the heart of “Are OZs Working? What the Literature Tells Us,” a paper published in October by Kenan Fikri and Benjamin Glasner that surveys nine valuable and oft-cited studies of the OZ program. Fikri is director of research and Glasner is associate economist at the Economic Innovation Group, the “bipartisan public policy organization dedicated to forging a more dynamic and inclusive American economy” co-founded by Napster founder Sean Parker, John Lettieri, and Steve Glickman that championed the Opportunity Zone concept from inception and has the archives to prove it.

I talked to Fikri the day after the research brief was published. He summed up the findings about the research studies as the data environment has evolved from “very poor” to decent: “Those who stopped data collection around 2019 found generally limited effects of OZs on commercial and residential property prices,” he says. “In the more recent studies that looked at things like building permits and construction jobs, lo and behold, they found a generally positive effect of OZs.”

The research brief builds on work from earlier in the year that looked closely at a U.S. Treasury Department working paper called “Use of the Opportunity Zone Tax Incentive: What the Data Tell Us” and a November 2022 paper by UC-Berkeley economist Harrison Wheeler that examined, among other information, new data sets on residential and commercial construction projects across some 12,000 census tracts in 47 large metro areas. Based on privileged access to IRS records, Treasury reported around $48 billion of direct OZ capital in Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) raised across around 3,800 census tracts (48% of all OZs) by the end of 2020.

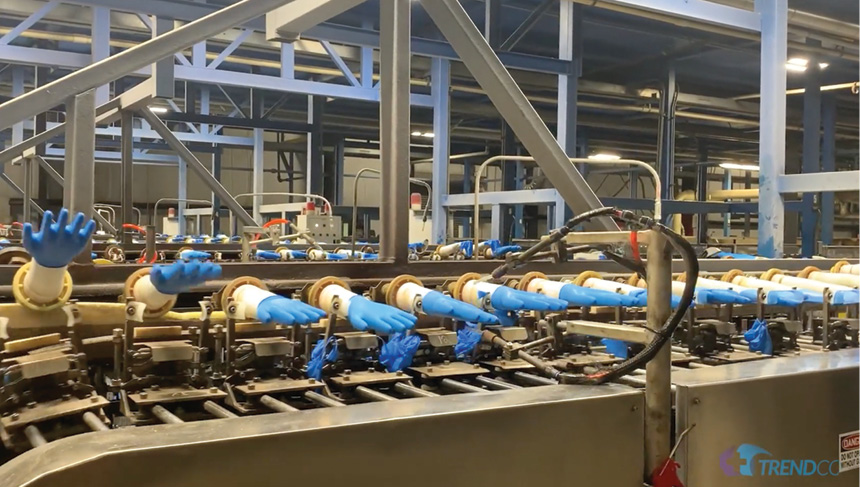

Photo courtesy of Trendco and Alabama Dept. of Commerce

“For us, that was a surprising breadth of OZ investment already by the end of 2020,” Fikri says, since full regulations didn’t really kick in until 2019. Meanwhile, data from Novogradac, which Fikri calls the best private information out there, showed a steep increase in fundraising in 2021 and 2022, tapering or plateauing in 2023, to a total of at least $100 billion in OZ equity flowing through the program so far, Fikri says.

Wheeler reports that while there was “no evidence of systematic differences in new construction between OZs and comparable areas in the four years leading up to the program,” after OZs were approved, “I find a large and immediate effect of the tax credit on new development. My main estimate is a 2.9 percentage point (pp), or 20.5%, increase in the monthly probability of new development. The effects increase over time.”

“One thing that comports with all the anecdotal evidence is they find a significant development response in vacant and underutilized urban areas,” Fikri says of the Wheeler paper. “Think of the periphery around downtowns, semi-industrial, full of parking lots and vacant buildings. Those areas are most responsive to the OZ incentives for a particular type of infill and redevelopment opportunity.”

Multifamily has been the hot sector in OZs. Asked for examples of projects that are more employer-based, Fikri mentions several. Last year The OPAL Fund (managed by a subsidiary of Opportunity Alabama) made an OZ investment in the development of Building 100 at the Regional East Alabama Logistics (REAL) Park, a 6.2 million-sq.-ft. industrial park in Macon County — a rural, underserved county in Alabama’s Black Belt region.

In August, South Carolina–based Trendco USA announced it would invest $43 million to launch a manufacturing operation and Tuskegee logistics hub at the park, where the company will produce nitrile medical gloves to expand domestic supply and create up to 292 jobs over the next five years. “We created The OPAL Fund to invest in catalytic projects that could produce compelling returns for both investors and communities across Alabama and Building 100 is the perfect example of that thesis in action,” said Alex Flachsbart, founder and CEO of Opportunity Alabama (OPAL) and principal of The OPAL Fund.

Other examples involve Exceler Building Solutions in Hazleton, Pennsylvania; S&K Holdings, a personal healthcare services company, in Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County and Altoona’s Blair County; and aerospace startup Agile Space Industries in Durango, Colorado.

Fikri says the growth of demonstration cases is showing how an OZ can blossom for a community and for investors. “That’s going to continue as more corporate entities recognize OZs as a tool to finance expansion and growth,” he says. “For companies that are growing and have patient capital, who are in this for the long haul and want to be adding to the stock of distressed places in particular, OZs should be something they are considering. You could imagine a corporate client wanting to purchase a historic building for workers and move its headquarters into an OZ. If they’re going to invest a lot into improving it, it’s a perfect OZ investment. It’s right out of the playbook, the sort of thing OZs are well suited to.”

Congress is considering the Opportunity Zone Transparency, Extension and Improvements Act, which among its features aims to make estimating the costs and benefits of the program a much clearer process. Components of the act call for better metrics, the extension of the the investment and deferral period for qualifying investments to the end of 2028 and the designation of certain unpopulated former industrial brownfield tracts as OZs.

“It has bipartisan support,” Fikri says, “and is really viewed as an essential and uncontroversial piece of legislation.”

As lawmakers weigh the legislation, they’ll no doubt be turning to EIG’s work, where Fikri and Glasner conclude that “a close look at the most comprehensive data already makes clear that OZs are breaking new ground and challenging us to reimagine what federal tax policy can achieve in chronically distressed parts of the country.”