Few doubt that the information and communication technologies economy will dominate in coming years and the presence of ICT clusters will continue to support metropolitan areas in Europe. With manufacturing shifting to lower-cost production platforms in Central and Eastern Europe or Asia, and limited space for construction and agriculture, Western Europe needs to rely on high-value-added products, including information and communication technologies. Although the bursting of the Internet bubble in the early-2000s interrupted rapid growth of the ICT sector, high-tech employment jumped by 18 percent between 2000 and 2014, while total employment surged only by 8.5 percent over the same period in Western Europe.

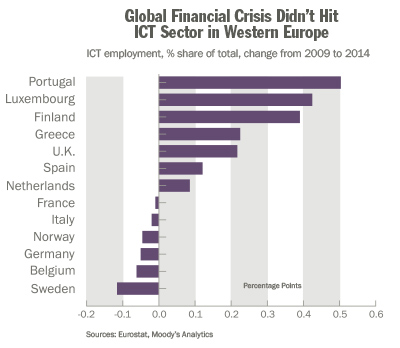

Even the global financial crisis, which hit in 2008, didn’t have a significant impact on the ICT sector, as high-tech employment remained virtually unchanged, while total employment shrank across Western Europe. Harsh austerity measures implemented by governments didn’t hit the ICT sector and businesses improved their competitiveness through innovation and technological improvements, securing jobs for ICT companies (see chart).

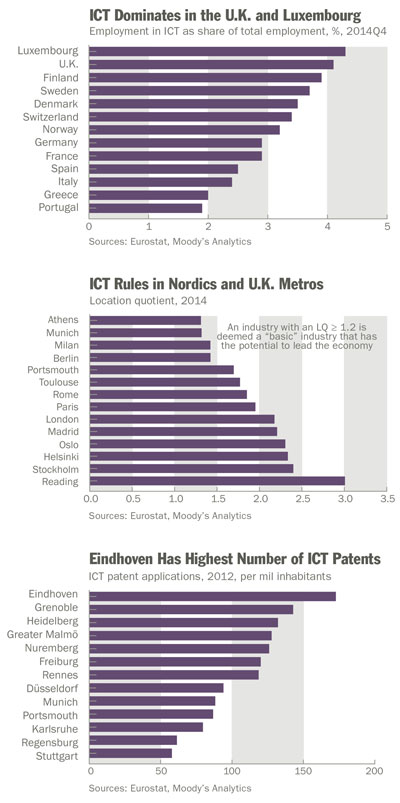

In Western Europe, Luxembourg, the UK and the Nordics have the highest share of employment in the ICT sector. Not surprisingly, Portugal, Greece, Italy and Spain, which performed worse during the crisis, have the lowest share of high-tech employment. The contrast suggests that countries with higher concentrations of ICT jobs can overcome economic downturns more easily and keep their economies more competitive than other countries (see top chart).

Large Metro Areas Lead

Within countries, however, large differences also prevail. To analyze whether the ICT sector drives the economy of a particular metro area, a simple measure called a location quotient can be used. The location quotient (LQ) calculates the relative concentration of employment in the ICT sector in a metro area versus its concentration across Western Europe.

While the ICT sector dominates in Europe’s largest metros, the concentration of ICT jobs lags in smaller metro areas. Especially in the Nordic countries, ICT jobs are concentrated in capitals, with the location quotient rising to 2.4 in Stockholm, 2.3 in Helsinki and Oslo, and 1.9 in Copenhagen. Besides the Nordics, the UK’s Reading, London, and Cambridge areas rank high because of the presence of universities (see middle chart).

Tech businesses such as Spotify, Mojang, Wrapp and SoundCloud have played a key role in Stockholm, as the government is offering competitive tax incentives for startup companies. The metro area is home to around 700 high-tech companies located in its Kista neighborhood, supported by high government’s spending on R&D and the country’s excellent education system. The tech expansion looks primed to mature, thanks to prudent government policy which has extended Internet access to more people than ever.

In contrast, the possibility of further layoffs at Microsoft poses a risk to Helsinki’s outlook for scientific and technical services after Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia Oyj’s consumer electronics division. Nevertheless, Helsinki remains a center of technology and engineering talent, and Nokia’s planned acquisition of French telecommunications firm Alcatel-Lucent will boost the metro area’s prospects.

Larger metro areas generally are more efficient economies because of the agglomeration of industries. Information technology companies, more than those in other industries, tend to cluster because of high demand for skilled labor and easier access to financing through capital markets.

In Berlin, for example, with the highest LQ among the German metropolitan areas, investment in ICT startups reached a new record in 2014, with €2.24 billion paid to 362 companies, according to the German Private Equity and Venture Capital Association. Berlin led the 16 German states with 98 funded enterprises, well ahead of the 57 in Bavaria, with its Munich metropolitan area, and 50 in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Apart from easy access to capital markets, adequate supply of office space, transport links and high-quality Internet access, the larger metro areas also offer a highly-educated workforce. The relationship between location quotient and people with tertiary education employed in science and technology shows that higher concentrations of skilled labor support the ICT clusters in the European metro areas.

Around 60 percent of those working in information technology firms in London, Oslo, Zurich, Stockholm, Helsinki, Paris and Reading (close to Oxford University), where the ICT sector dominates, hold tertiary degrees. Meanwhile, in Lyon and Grenoble, part of the Rhône-Alpes region in France, around 50 percent of ICT employees are university graduates.

Pros and Cons of Clustering

The presence of an ICT sector can lift economic output in metro areas through higher wages and value-added production resulting from innovation. The number of ICT patent applications can be used as a gauge of innovation in a metro area. The number of patents also indicates how efficient the metro area’s ICT sector is and if clusters can contribute to economic growth. The relationship between location quotient and patent applications shows that a stronger ICT cluster supports more patents (see chart).

In 2012, the region’s highest number of ICT patent applications was in the Dutch city of Eindhoven, whose High Tech Campus has developed into a dynamic mix of more than 125 corporations, leading research institutes and high-tech startups. Eindhoven was followed by Grenoble, Heidelberg, Greater Malmö, and Nuremberg. Many research institutes associated with the University of Heidelberg focus on ICT, sharing high-tech facilities and benefiting from the nearby head office of German multinational software company SAP.

In contrast, the Central and Eastern European metro areas have lagged behind their Western European peers, suggesting that global ICT firms still locate their research departments in Western Europe, instead of moving them into lower-cost metro areas.

With rapidly rising ICT sectors across European metro areas, the tech industry is suffering from a skills and housing shortage. The increasing shortage of skilled workers represents a key headwind for German metropolitan areas, including Munich and Berlin, while high rents and low housing availability have persuaded startup business owners to move operations away from Stockholm. Longer term, infrastructure will also increasingly pose constraints. For example, the capacity of London’s airports needs to be expanded to avoid restricting business activity.

Tomas Holinka, based in Prague, is an economist at Moody’s Analytics. For more information, visit www.moodysanalytics.com.