Despite overwhelming evidence that state and local tax incentives are having little to no positive effect on promoting real economic growth anywhere in the country, states continue to up the ante with richer and richer incentive programs. This is occurring despite the extreme fiscal stress confronting almost all state governments. Moreover, as federal tax dollars continue to prop up state government expenditures, there are real questions as to whether the interstate competition for jobs is a wise use of anyone’s tax dollars and, if not, then what can be done to at least slow down this zero sum game?

To be clear, there is a myriad of sound economic development programs that make effective use of tax credits and incentives. The issue is how to slow down the hugely expensive interstate competition for jobs so that scarce state fiscal resources can instead be focused on strategies that promote real economic development and growth as opposed to simply chasing scarce projects or fending off challenges from neighboring states.

In discussions with senior state policymakers from around the country, it is clear that most would prefer to end many of the incentive programs offered by their state but equate such action with unilateral disarmament: a fear that their companies will be lured across state lines by aggressive neighbors that will continue to offer seductive awards, or that they will be unable to compete for projects because other states offer lucrative incentive packages that their state will no longer be able to match. This is not an irrational fear. States need some mechanism for leveling the playing field. One solution is for the Internal Revenue Service to revisit the federal tax treatment of state and local economic development incentives.

Manna From Heaven

While the federal tax treatment of state tax incentives is extremely complex, it is not an oversimplification to say that in general the following conclusion from the IRS Coordinated Issue Paper (LMSB-04-0408-023 effective May 23, 2008) captures the generally accepted treatment of state incentive awards. It reads, “A state or local tax incentive, whether in the form of an abatement, credit, deduction, rate reduction, or exemption, is not an item of gross income under I.R.C § 61. Rather, such an incentive is a reduction of state or local tax expense. This is true whether the taxpayer first pays the tax and then receives a rebate or refund, or pays only the net amount.”

While the federal tax treatment of state tax incentives is extremely complex, it is not an oversimplification to say that in general the following conclusion from the IRS Coordinated Issue Paper (LMSB-04-0408-023 effective May 23, 2008) captures the generally accepted treatment of state incentive awards. It reads, “A state or local tax incentive, whether in the form of an abatement, credit, deduction, rate reduction, or exemption, is not an item of gross income under I.R.C § 61. Rather, such an incentive is a reduction of state or local tax expense. This is true whether the taxpayer first pays the tax and then receives a rebate or refund, or pays only the net amount.”

This conclusion suggests that economic development incentives are treated as an extension of state tax policy and the value of the benefit received is not income but a modification to state tax liability. While that interpretation accurately describes a wide range of credits and incentives, it does not accurately describe the form or substance of many large incentives programs that are designed to lure companies or jobs from other states. Moreover, absent any bright-line test indicating otherwise, the overwhelming majority of tax managers treat all incentives received, regardless of their form and substance, as being an allowed offset to taxes paid, or simply as manna from heaven, acceptance of which results in no adverse tax consequence whatsoever.

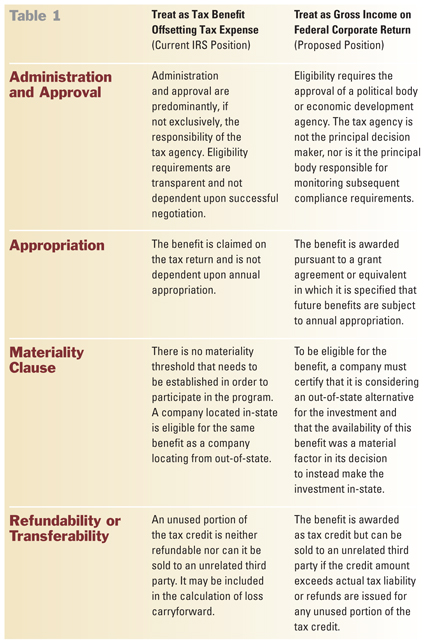

The most lucrative state economic development incentives that are used to lure jobs from one state to another typically have characteristics that make them easily distinguishable from bona fide tax credits and incentives that do, in fact, conform to the IRS interpretation. Incentives that ought to be treated as income as opposed to being a simple extension of tax policy are often administered and approved by entities other than the state tax authority, subject to annual or special appropriation, conditioned upon satisfaction of a materiality test, or able to be sold to an unrelated third party.

When any of these conditions are met, the Internal Revenue Service should treat the benefit as income for federal corporate tax purposes; rather than as a reduction or offset to state tax liability. This change in tax treatment would not eliminate or prevent states from offering large discretionary awards as is their right (see DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno; U.S. Supreme Court).

Treating discretionary awards targeted to specific companies as gross income, however, would blunt the economic value and diminish the effectiveness of these programs and presumably scale back their use. If the states are really serious about finding a way to escape the escalating costs of fending off aggressive neighbors or luring potential prospects, the adoption of this distinction between offset to tax liability (current treatment) and gross income (proposed treatment) will go a long way toward achieving that end. Table 1 highlights four key ways in which incentives that are in form and substance a financial subsidy that ought to be treated as gross income can be distinguished from a credit or incentive that in form and substance is a modification to state tax liability.

When reviewing the table, it is important to recall that the overwhelming majority of existing state credits and incentives meet the IRS standard of being an offset to state tax liability and comply with all conditions described above under “Current IRS Position.” On the other hand, it is hard to think of a significant economic development incentive designed primarily as a tool to entice out-of-state economic development prospects that does not violate at least one of the conditions described above and that would consequently cross a bright-line test triggering classification as gross income (“Proposed Position”). A company’s state tax liability is not determined by a discretionary negotiation led by non-tax officials nor is it dependent upon a special budgetary appropriation. Therefore it cannot reasonably be concluded that awards obtained in such a manner and with such characteristics are in fact mere extensions of state tax policy. Similarly, when a “tax credit” can be sold or transferred if unutilized it ceases to have a meaningful connection to state tax liability. Instead, in such circumstances the award of tax credit is merely a delivery mechanism for state subsidy — the value of which has nothing at all to do with actual tax liability.

Adoption of these proposed bright-line tests will not prevent states from offering tax breaks and incentives to companies making investments that promote state economic development objectives, nor will it prevent a state from actively marketing itself to a prospective project. What the proposal will do is to blunt the effectiveness of offering large financial incentives to companies considering or threatening an interstate search for a project site, and instead encourage states to adopt incentive policies that promote economic development investments equally from in-state and out-of-state businesses, as well as limit the use of refundable or sellable tax credits to disguise actual cash subsidy. A brief examination of how the proposal would be applied in a few commonly utilized economic development programs will help illustrate the types of programs that would be limited by this proposal and those that would be wholly unaffected.

Enterprise Zones. Many states award favorable tax treatment to any company that locates to or invests in a facility located in a geographically defined enterprise zone. Typically these zones are in distressed communities or other locations deemed by the state to be in need of economic development assistance. Zones typically encompass areas that include more than one business and do not distinguish between businesses that locate to the zone from an in-state or out-of-state location. Tax agencies typically approve and administer the tax benefits allowed to companies located in the zone. Under these circumstances the tax benefit received as a result of location in the zone would not be treated as income.

Job Creation Tax Credits. One of the most common tools for economic development is to award tax credits for each job a company creates. In most instances, the value of the credits is fixed per job created or fluctuates based upon established formula (e.g., function of wages paid or number of jobs created). Provided that the credit is made available equally to businesses located in-state as well as those locating from out-of-state (see rules on approval and materiality) the value of these credits would be treated as an offset to tax liability and not be included in income. There are some examples where the amount of the credit is a negotiated matter that typically favors an out-of-state company locating in-state, and other cases where these credits are refundable. In those instances the value of the credit would be treated as income (see rules on approval, materiality, and refundability).

Payroll Tax or Payroll-Based Rebates. Among the most lucrative of all state incentive programs are those that rebate to qualified applicants a portion of the payroll or state payroll taxes attributable to new employees of the applicant. In most instances, these awards require pre-approval by non-tax officials, include materiality requirements, are subject to annual appropriation and therefore would be treated as taxable income under this proposal.

Discretionary Grants. Many states make use of discretionary grants that are typically structured as reimbursement of certain project costs associated with relocation or investment. Often these costs are associated with employee relocation, site preparation, or employee training. These grants would be treated as income (see approval and materiality). The company typically does incur real project costs, and these costs are fully deducted as allowed expenses on the tax return. The award of a grant that reimburses these fully deducted expenses is therefore reasonably classified as income.

What makes for an effective economic development strategy is often in the eyes of the beholder. Most state policy makers welcome an opportunity to offer large cash incentives to out-of-state companies considering a move to their state but fume with indignation when a neighboring state uses the same techniques against them. The result is a race to the bottom in which states are spending increasingly precious resources simply trying to maintain the status quo.

Creating bright-line tests to be used by the IRS to help it determine when an economic development incentive ought to be treated as gross income will not stop the interstate competition for jobs but it certainly will help slow it down.

Until then, the states will find it increasingly difficult to fund and focus on economic development programs that benefit small and mid-sized businesses, revitalize distressed communities, promote meaningful university-business partnerships, and engage in other initiatives that promote sustainable economic growth.

Like all contests, the interstate competition for jobs would be better played with an impartial referee.

Daniel Levine is Principal, MetroCompare L.L.C., a business strategy consulting company specializing in corporate relocation and economic development. He can be reached at Levine@MetroCompare.com.