PLEASE VISIT OUR SPONSOR ? CLICK ABOVE

|

|

Is a Corporate Campus Right for Your Business?

But is a corporate campus the right solution for your organization? If your company occupies 250,000 square feet (23,225 sq. m.) or more, you’ve probably posed this question. America Online did, and decided the answer was yes (see Site Selection cover story, August/September 1998). SRA International, on the other hand, decided the answer was no. To find the right answer, it’s important to go through the right evaluation process, one which examines intangible issues as closely as the tangible ones.

What Is a Corporate Campus?

Although there are opportunities for significant financial benefits, it is likely a company will make the decision whether or not to go the campus route based on more intangible issues: operational, business performance and cultural. Operational issues address how facilities support day-to-day functions and evolving space requirements. Business performance issues examine the effects of the different ways employees communicate, collaborate and share knowledge. Cultural issues delve into how connected the employees feel to the company and to each other. The tangible financial considerations come into play once a company decides a campus is worth considering.

Intangibles: Operations, Business Conversely, there are also drawbacks: most notably, if a company downsizes, it will be burdened with excess space. If the property goes on the market, other organizations might not find the custom-designed facilities easily adaptable to their needs. And — even if the organization never has to consider releasing any space — if the corporate mission changes, the custom-designed facilities might not support the new business. Finally, as the party in control of the project schedule, the company must ensure that it has the experience and resources to drive this process effectively. In addition to evaluating operational factors, companies should consider the impact of a corporate campus on business performance. Locating people together bolsters communication and exchange of knowledge. Even with today’s technology and methods of instant communication, such as video conferencing and e-mail, it is a commonly accepted fact that bringing employees together fosters better collaboration and greater synergy. Also, bringing people together can result in less absenteeism and lower attrition rates — and better business performance. Cultural factors also come into play in the evaluation process. Is it beneficial to your company to have a strong sense of corporate culture, and for employees to feel more tangibly connected to the company? If the answer is yes, locating employees together on a corporate campus can achieve these goals. Housed together, employees can develop a greater sense of loyalty and commitment to the company. However, consolidation can also have some negative effects. Employees can develop “corporate headquarters syndrome”– they can become too isolated from the field and not have the sensitivity to what is happening on the front lines. They might feel as though they don’t have enough exposure to other situations. But this effect is noted most often for companies who have developed campuses remote from their customer base and target markets.

The Tangible Issue: Finance Additionally, an ownership position in a corporate campus affords a company a much greater opportunity to control its long-term real estate costs. For instance, if a company leases its facilities, landlords can dictate capital improvements schedules. Conversely, if a company owns its facilities, improvements can be sequenced to benefit its financial position. And other municipality expenses can be reduced. Companies can look at it this way: if the company is going to need the space, why not pay for it now rather than later, presumably at a lower cost? Again, rather than viewing real estate as an investment vehicle, it should be viewed as cost avoidance. There were a number of professional facility managers who financed corporate real estate transactions in the 1980s with the objective of profiting in the market; they were obviously disappointed in the early ’90s. If a company decides to implement a corporate campus, one of the keys is securing available capital. Many organizations cannot support the debt. If a company is not profitable, it is unlikely it will be able to finance internally. But if a corporate campus makes sense, there are alternative ways to structure a deal. If using a company’s own money is not an option, there are other financing vehicles such as equity partnerships, synthetic leases and other corporate or real estate debt. And for those companies that are able to secure the necessary capital for a campus, there is an obvious drawback: It’s a lot money going into one place. This concern is what prompts many solvent corporations to team with developers. As a general rule, corporations should not try to play real estate developer. If a company decides to involve a developer, it should recognize that the developer’s interests will come into play as well. Corporate real estate consultant Don Young of PMC International, San Rafael, Calif., reminds clients: “Remember that a build-to-suit project is often built to suit the developer, not the user.” (See Management Strategies Site Selection, June/July 1998.) Financing over the full life of the project constitute the largest project cost, perhaps as much as 80 percent. Between construction financing and permanent financing, construction financing is a much higher cost; the risk is higher because there is no final product. (Once the project is completed and there is a usable product, the risk is lowered.) In general, the rule to remember is that whoever can borrow money at the lowest rate should be the primary owner and developer of the property. If a company is very profitable and has AAA credit, it can use corporate debt and borrow at a very low rate. Perhaps it can borrow at 8 percent while the real estate developer can only borrow at 9 percent. In this case, the company itself is in a good position to do it. While this approach is defended in many circles, it is important to keep in mind that this presumes predictability in the company’s need for the space. Here is another consideration: If a company has a sustaining need for the facilities on a corporate campus, it is much better off investing in a campus than it is leasing, because it can control its long term costs. But if the company’s need changes, what is it going to do? The answer depends on the location and product. If it doesn’t have a generic or easily adaptable product in a demand market, a corporate campus can be a noose around the company’s neck.

Don’t Build a Submarine Companies that have opted for corporate campuses cite the benefits, both tangible and intangible. Several years ago, after significant growth, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Co. (Freddie Mac) decided to move employees from eight scattered facilities into a 900,000-sq.-ft. (83,600-sq.-m.) suburban campus in McLean, Va. Bill Menda, interim vice president of administration and corporate properties, points out that it was the right thing to do. “A corporate campus afforded the best opportunity to consolidate,” he explains. “It positioned us for planned expansion. Also, cultural considerations were important. We knew that one way to help our culture develop was to keep people together.” Freddie Mac continues to be a successful company, says Menda. “We like to think that our environment and our workplace contribute to that.” Corporate leaders throughout America who have evaluated whether or not to develop a corporate campus have come to different conclusions, but agree on one major issue: If your decision-making process is sound, the solution will be the right answer for your business.

| This Issue | Site Selection Online | SiteNet | ©1998 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and is not warranted to be accurate or current. |

PLEASE VISIT OUR SPONSOR ? CLICK ABOVE

JANUARY 1999

JANUARY 1999 The decision to plan and build a corporate campus consists of dozens of often conflicting considerations, both tangible and intangible. If the corporate real estate executive wears many hats, here’s where he wears them all at once.

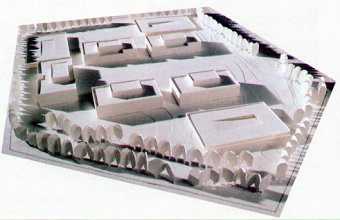

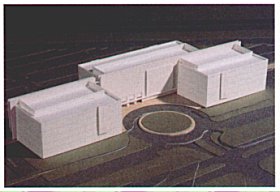

The decision to plan and build a corporate campus consists of dozens of often conflicting considerations, both tangible and intangible. If the corporate real estate executive wears many hats, here’s where he wears them all at once. The buildings on an urban campus are adjacent but not necessarily connected. An ex-urban campus is located close to the urban core, where costs are high, so the buildings are proximate to each other and parking is usually under the buildings or in an adjacent garage. Since land costs are less, a suburban campus affords more opportunities for open space and more parking options; there is often freestanding structured parking or surface parking, or a combination of both.

The buildings on an urban campus are adjacent but not necessarily connected. An ex-urban campus is located close to the urban core, where costs are high, so the buildings are proximate to each other and parking is usually under the buildings or in an adjacent garage. Since land costs are less, a suburban campus affords more opportunities for open space and more parking options; there is often freestanding structured parking or surface parking, or a combination of both.

David T. Haresign is a principal of Ai, a Washington, D.C.-based firm specializing in strategic planning, architecture, interior architecture and engineering services.

David T. Haresign is a principal of Ai, a Washington, D.C.-based firm specializing in strategic planning, architecture, interior architecture and engineering services.