“My best friend died today.”

With those crushing words, Laura Lyne broke the news to the world that on December 3, award-winning journalist Jack Lyne’s story had come to an end.

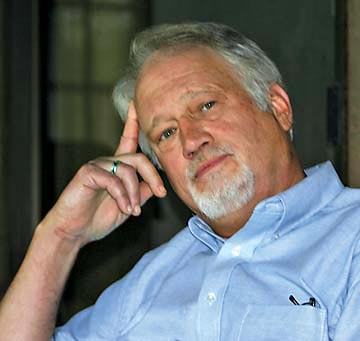

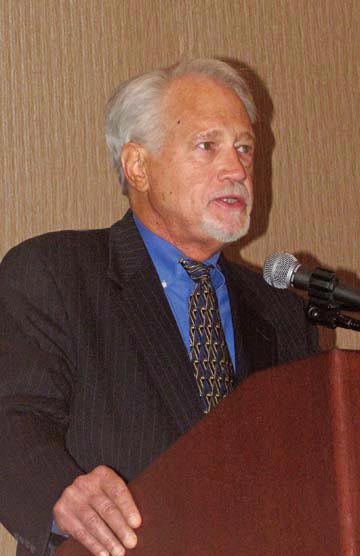

Jack was an extraordinary writer who perfected his craft by agonizing over every word he wrote. He became the leading editorial voice of a generation of reporters covering the practice of corporate site selection.

This was no small feat.

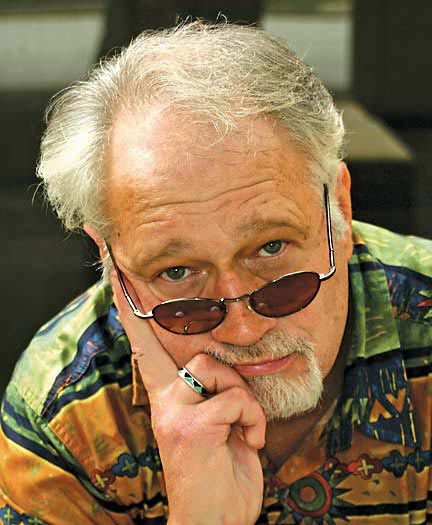

Not only was there plenty of competition for that mantle, but Jack never envisioned himself as a sage to corporate boardrooms. In fact, he always identified more with the counterculture movement of journalists like Hunter S. Thompson and Guy Mendes than he did with the likes of the more buttoned-up Cable News Network.

So it was only fitting that the empire of media mogul Ted Turner brought the “hippie” Jack Lyne to Atlanta and set him on a path to change the discourse of corporate location decision-making.

How a basketball-loving kid from small Russellville, Ky., could become the world-renowned editor of Site Selection Magazine and the witty voice of SiteNet is the stuff of storybook legend, and yet every bit of it is true.

Not that he would ever take credit. Jack once described himself as “one of the ink-stained wretches” of journalism. “My only skills,” he said, were that “I watched; I remembered; I documented.”

Boy, did he ever. He watched, remembered and documented his way through a 67-year life that touched so many and impacted the way that we looked at the world.

And he never did anything halfway. Whether it was meticulously documenting reform efforts in Louisville’s segregated public schools in the 1960s and 1970s or writing an exhaustive article in 2003 about a planned underwater hotel in Dubai, Jack was at his best when pursuing a story with big stakes.

He didn’t just write an article. He immersed himself in every project with an almost obsessive ferocity. His wife remarked that “watching Jack write a story was sometimes like watching sausage made. You just didn’t want to see it done. He was so intense and absolutely determined to get every nugget that could be wrestled out of the story and put it into words — into the absolutely perfect combination of words — that it was painful to watch. I frequently tormented him by suggesting he just let me finish a story. (He knew I’d chop and hack it together into a passable ending, but not one with the flair and panache that he fully intended for it to have. Besides, he just couldn’t let it go until it was right.)”

When Jack was on the trail of a story, it usually took him longer than anticipated to complete the assignment, but you could always be assured of two things — he would get the story right, and it would be the best account you would ever read on that subject.

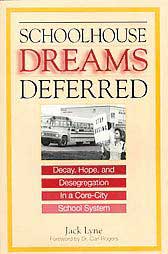

That Jack labored so much over every piece he wrote — indeed, over every word — was evident when he penned the following introduction to his own book, “Schoolhouse Dreams Deferred: Decay, Hope, and Desegregation in a Core-City School System”: “Parts of it strike me as painfully overwritten and extravagantly overburdened with detail.”

That may have been true, but what joy he gave to readers with each carefully constructed sentence of insightful prose.

Even when describing himself with his typical self-effacing modesty, Jack made readers smile. He noted that his book about the massive upheaval in the Louisville school system had been written by “this naïve, impetuous lad, a recent master’s graduate from the University of Kentucky hailing from Russellville (pop. 7,500). I was a rough beast bristling with brash judgments. And, in more ways than I could’ve possibly imagined, I was as square as a pool table and about twice as green.” (Obviously, Jack never played enough pool to know that the tables weren’t square.)

The Kentucky Kid

For a rough beast, he sure made a lot of friends, including those who were fortunate to work alongside him as a colleague.

The great photojournalist Guy Mendes, a contemporary of Jack at the University of Kentucky and a fellow co-founder of the underground newspaper The Blue-Tail Fly, said that “Jack was something else — smart, handsome and very talented. He was the best writer of a group of us that went on to work for major newspapers, national magazines, news services and public broadcasting. He was a prose stylist who was greatly influenced by the emergence of the New Journalism of Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, Ed McClanahan and others. He told it like it was, with a flourish.”

He lived life that way, too.

Growing up in tiny Russellville, he threw himself into his two great loves: basketball and more basketball. He played one year of football in high school, but he always played basketball.

Not particularly gifted athletically, and burdened with poor eyesight (his vision was about 20/400 without corrective lenses), he got by on hustle, grit and sheer determination. He shot baskets so much, often sneaking into closed gyms late at night to hone his shot, that he literally made himself into an accomplished player.

“His coach once told him he was the sweatiest white boy he had ever seen,” said Laura, his beloved wife and soulmate of 20-plus years. “He always practiced. He shot baskets forever, even though he was practically blind.”

His eyeglasses were so thick that he refused to wear them during games, at least he did until the coach caught him guarding the wrong identical twin on the court. “He didn’t know there were two guys that looked exactly alike, and the coach pulled him out of the game and asked to see his glasses,” Laura recalled. “After that, Jack had to wear his glasses each game.”

Still, he persisted, enough that Western Kentucky talked about a scholarship.

But something else back in those days tugged at his heart even more — the desire to prove something to his father. Though his dad was an accomplished attorney and political leader in Russellville, as was Jack’s grandfather, Jack struggled to earn his dad’s affirmation.

“Jack was so determined to be the best he could be at anything he tried because his father told him he would never amount to anything,” Laura said. “He knew he’d never go anywhere in basketball, but he knew he had chances for a good career in other areas.”

Jack decided to try pre-law at UK in Lexington. The dabbling in law turned out to be only that, and he quickly changed his focus to political science, history and journalism.

He stayed long enough to earn both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UK while teaming up with classmates like Mendes to raise some rabble and rattle the teeth of university administrators and other members of the establishment.

Forty years later, he would return to Lexington to be inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame. Established in 1980 by the University of Kentucky Journalism Alumni Association, the institution honors “Kentuckians who have made significant contributions to the profession of journalism.” Its members include ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer, veteran White House reporter Helen Thomas and Sirius Radio host Bob Edwards, the long-time host of NPR’s “Morning Edition.”

Heeding Ted Turner’s Call

Jack’s “significant contributions” included being an on-air news commentator for CNN in Atlanta. His television work also included on-air commentaries for the Kentucky PBS outlet in Lexington.

Early in his professional life, he worked as a reporter for The Louisville Courier-Journal and then as director of public relations for the Louisville Public Schools. There, he created, wrote, edited and designed a newsletter that won the Educational Press Association of America’s highest honor, The Golden Lamp, awarded annually to only one U.S. publication.

It was his stint at Louisville Public Schools that prompted him to write “Schoolhouse Dreams Deferred” (1998, Phi Delta Kappa Press). Eminent psychologist and author Carl Rogers wrote the foreword for this book and called it “a straightforward account of one of the boldest attempts at educational change that has been made in this country.”

Like most journalists at some point in their careers, Jack eventually found himself out of work. Someone in Ted Turner’s vast media empire at CNN determined that Jack’s on-air show should be dropped, and so it was.

In 1984, sudden unemployment meant that Jack needed to find another outlet for his creativity, preferably one that came with a paycheck.

Conway Data Inc. in Atlanta was advertising for a magazine editor for a publication called Site Selection. He decided to apply for the job.

Mac Conway, the founder and chairman of Conway Data and publisher of Site Selection, typically knew a good journalist when he found one, and so he offered Jack the job.

Michael O’Connor, information manager for Conway Data, joined the company around the same time as Jack and recalls those days quite well. “Jack was a commentator at CNN before coming to work for Conway Data, and one day we persuaded him to show us some clips from his days at CNN,” O’Connor said. “What we saw was classic Jack. In his typical easygoing manner, Jack offered up some thoughtful insight with a huge dose of his terrific sense of humor. I’m not sure how CNN let him get away, but their loss was our great gain.”

Jack would serve as editor of Site Selection for 17 of his 27 years with the company. In 2001, he became executive editor of interactive publishing, a role that would see him serve as editor and primary author of the SiteNet Dispatch, a weekly online newsletter.

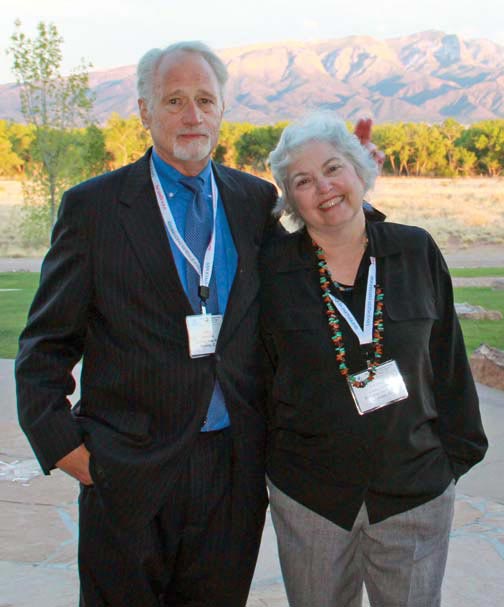

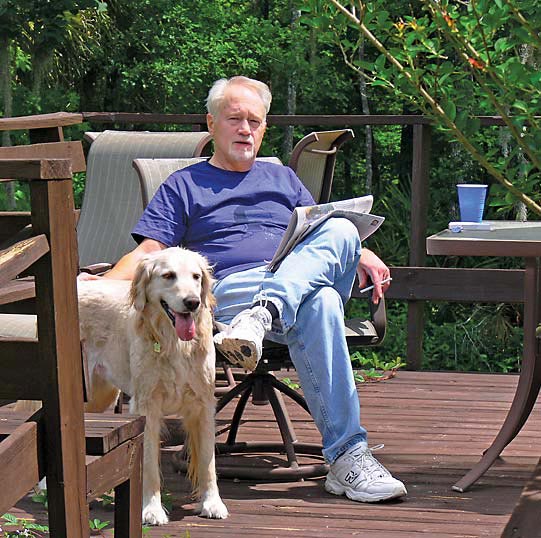

He performed his online journalism role, appropriately enough, remotely from his home in rural Shiloh, Fla., where he lived with his wife, Laura, the president of Conway Data. Each week, Jack would sign off his newsletter with a salutation that became his signature quip — “Copacetic Clicking, Jack Lyne.”

Throughout his career, he earned the highest of journalism’s honors. His work repeatedly received awards from the Magazine Association of the Southeast (MAGS) and the Awards for Publication Excellence (APEX), including two Grand Awards, APEX’s highest honor.

Gary Nickerson, former webmaster for Conway Data and long-time colleague of Jack, spoke for many when he said, “Jack was not only a witty and engaging person, but he was the finest writer I ever had the pleasure of working alongside. Time after time, Jack weaved seemingly ordinary topics into compelling and fascinating stories. He was a rare talent, a respected colleague and a valued friend.”

A Unique Bond With Readers

Some of the highest praise for Jack came from those he served — his readers. Leaders in corporate real estate and economic development regularly looked to his work as a guidepost for navigating complex issues.

“Jack Lyne was one of the thought leaders in the field of site location and economic development,” said Jeff Finkle, president and CEO of the International Economic Development Council in Washington, D.C. “He certainly made a career out of learning what was best practice in our fields and feeding it back to all of us in ways we understood. He could take a technical subject and simplify it. He could help us explain what we did and how we did it. These are certainly the tools of every editor, but he was a master of it. He was special because of the way he approached his job and those of us in the field. He will be missed.”

Charles McSwain, former chair of the Industrial Asset Management Council and former director of real estate for CSX in Jacksonville, Fla., said that “Jack was an affable, inquisitive professor in the school of life-long learning. Jack felt a real calling to dig out the meat of an issue or idea, and craft its most useful meaning for dispatch to the busy professionals who regularly searched for his ‘by-Lyne.’ I know. I was one of them.”

Readers like Finkle and McSwain genuinely enjoyed reading Jack’s work because they genuinely liked the writer. A case in point was a 2010 exchange between Robin Ronne, the managing director of the CEO Council for the Greater Fort Lauderdale (Fla.) Alliance, and Jack.

“After he was named to the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2010, I sent Jack a congratulatory note saying that he was truly at the pinnacle of his profession and how proud I was of all he had accomplished,” said Ronne. “His response was, ‘Thank you so much, my friend. I’m thinking maybe they had an error with the voting machines, so I’m trying to move up the induction ceremony to get this thing officially in the books. Seriously, thank you so much for your very kind words. They mean a lot to me.’ Typical Jack — always self-deprecating and able to make you smile — whenever you saw his face, heard his voice or read his words.”

The one thing seemingly everyone who knew Jack agreed on was that he was always gracious, and none could recall having heard him utter an unkind word about anyone.

Mark Arend, editor in chief of Site Selection and Jack’s colleague for 15 years, said, “Jack had a bottomless reservoir of genuineness and warmth that he drew on whenever I saw him with others or when I was in his presence. His gifts to me and my colleagues on the editorial staff at Site Selection include priceless friendship, a writing standard that always seems out of reach, an editorial sensibility that is my gold standard as editor — and can only hope I am in the vicinity of — and a deep, smart and robust sense of humor.”

This was the great paradox: Jack genuinely loved others, even though he often preferred to be alone. His wife, Laura, even described him as “basically a hermit.” A hermit who loved people.

A Man For All Seasons

It was that innate shyness that kept him, for a while, from asking Laura out for a date when the two were working together at Conway Data in the late 1980s. Well, that and an intense distaste for spending time at the unemployment office. Laura’s father, you see, was Mac Conway, who had been known to devour employees for far lesser crimes than breaking his daughter’s heart. Given his history with women, Jack knew, just knew, that the relationship would end, and when it did he’d have to find other work.

Jack was also guilty of the mortal sin of being a Democrat. Growing up, Jack’s family was very political, his sister even describing them as “Yellow-Dog Democrats,” meaning they would actually vote for a dog before a Republican. Jack’s great-uncle, “Doc” Emerson Beauchamp, seemingly held every political office in Kentucky except governor.

Mac Conway was a rabid Republican and looked disdainfully upon anyone who disagreed with him (this applied to most other subjects as well.) So Jack, heretofore discreet about his political leanings around the workplace, also had to worry about facing the guillotine if he did something foolish like utter kind words about Jimmy Carter.

“He was scared to death to date me because of Mac,” said Laura. “He resisted for a long time.”

But the 46-year-old avowed bachelor recklessly threw caution to the wind and began dating the boss’s daughter, who had herself sworn off marriage and also believed the relationship would go nowhere.

That was 21 years ago. To the utter shock and amazement of those who knew Jack, not least his family — it’s rumored they offered Laura cash if she could get him to settle down — Jack proposed less than a year into the relationship (and proposed, and proposed; Laura resisted for six months before taking the plunge.)

In 1991, Jack wed Laura at a small private ceremony at Borthwick Castle in Scotland. And for two decades this was one of those marriages that just worked. Jack adored Laura, and he loved the fact that they were both huge basketball fans. The couple had basketball goals installed at every home in which they lived, and for years Jack bragged to his friends that his wife could actually beat him in intense games of H-O-R-S-E (they even had a 3-point line painted on the driveway — they were serious about their basketball.)

Laura describes a game many years and many joint-replacement surgeries ago when the two were playing a little one-on-one. “I remember trying to drive around Jack and go in for a lay-up one day (wasn’t the smartest thing I ever did). He responded by stepping in front of me and blocking the shot straight down into my face. That may have been the first time I realized that Jack was determined to win at everything he did. (He apologized after I finished spluttering at him, but didn’t apologize for blocking the shot — only for bouncing it off my face. He said it was my fault for trying to drive on him … which I pretty much never did again.) I should have realized that 5’5” doesn’t drive too well on 6’1”.”

These two weren’t just a couple. They were friends, friends who genuinely enjoyed each other, who always enjoyed life more together than apart. This was true in nearly every aspect of their life together. They loved watching most sports — football, baseball, the Olympics (summer and winter) — and Jack would brag with pride that his wife “knew the difference between a nickel-back and a halfback.”

In July 2011 the couple celebrated their 20th wedding anniversary. One month later, Jack joined former high school classmates to begin planning their 50-year reunion in Russellville. He had been senior class president, and when he returned to Kentucky people still looked up to him.

True to his Kentucky bluegrass roots, Jack would always deflect praise and quickly give credit to others for any success he achieved in life. Among them were Al Smith, whom Jack described as “a crack newspaper publisher and superb reporter” in Louisville; Jim Young and Howard Owens, his high school basketball coaches; Ruth Carpenter, his high school English teacher; and Granville Clark, whom he described as “barrister, wit, raconteur and all-around gadfly.”

“When I was very young, they all encouraged me to grow, to try, even though I might fail, but to try,” he recounted many years later. “That is something money can’t buy.”

His dogged persistence, so evident in how he approached every single piece he wrote, was never more on display than in the publication of his book, “Schoolhouse Dreams Deferred.” The book’s title may serve as well as a metaphor for Jack’s life. He wrote it in 1975. It was published in 1998.

When asked why he never attempted to rewrite it, he said, “I’ve decided to let the book be. Even if time allowed, I wouldn’t rewrite this overeager, earnest missive. This was how it felt, and some things are better left said, though they bring back a difficult, wrenching time that parts of ‘polite society’ might prefer quietly buried in the backyard. The heart, I suspect, really is wiser than the mind. And that, in a roundabout fashion, is who I am.”

Who Jack was is the essence of human decency and goodness of soul, the kind of person who radiates warmth and injects life into everyone around him.

Jurgen Lindhorst, another former colleague, wrote from Ontario, Canada, that Jack “struck me as a thorough professional when it came to his craft, yet most importantly, an enjoyable and decent person — would that there were more like him.”

Jack’s passing robbed us of more than just a superb writer. Conway Data lost an essential member of its management team, an intense competitor and journalist the likes of which we’ll not see again. And his wife lost her best friend, a man whose easy smile and casual charm made their 20 years together the happiest of her life.

That is why we all miss him so much. We know there won’t be another one like him, a master storyteller who combines intensity and passion for life with such preciseness of craft.

Now Jack’s gone. The rocking chair on his smoking porch sits empty, surrounded by piles of books and newspapers, the stereo full of treasured records from Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones and Miles Davis, now silent.

Jack has left us, and our lives are poorer for it.

As his sister, June Lyne Robinson, said, “Everybody who knew Jack loved him. There will never be another Jack Lyne.”