What if the new age of electric vehicles didn’t just mark a shift from internal combustion engines and fossil fuels but sparked its own closed-loop ecosystem?

In this case, the secret to being green is black mass.

That’s the term used for the recyclable material from battery gigafactory scrap and end-of-life lithium-ion batteries. The idea is central to a billion-dollar plan by a Massachusetts company that broke ground for such a future at a greenfield site in October 2022 in Christian County in Southwestern Kentucky.

“There’s always scrap,” Roger Lin, vice president of global marketing and government relations for Ascend Elements, said of the typical lithium-ion battery-making operation. Especially early in the plant’s life. “We estimate 6% to 10% of the output of a factory is scrap. Any battery factory that creates scrap is a potential customer of ours. Any factory that requires cathode active materials (CAM) is also a customer of ours.”

In both the supply and offtake senses, the factories served by Ascend Elements will “help us realize the circular economy we’re trying to achieve.”

With the current EV surge still in its early days, that means follow the battery gigafactories, which are popping up like wildflowers across the Southeast United States. That’s what led Ascend Elements to Hopkinsville, located in the heart of that activity and just an hour north of Nashville.

“We worked with 50 different sites throughout the Southeast,” said Lin, who serves on the board of directors at the U.S. Energy Storage Association. One requirement was proximity to the company’s “Base 1” facility in Covington, Georgia, which recently began operations to shred 30,000 tons of batteries a year to create that black mass. So the search began in and around Georgia, based on criteria such as clear height, power, zoning and access to labor. Greenfield was the best option, Lin said, “because there really isn’t anything like our factory anywhere in the country. It’s the first of its kind.”

Now the new facility in Hopkinsville — dubbed “Apex 1” — will consume that black mass and spit out CAM for new batteries. Lin said the community had a combination of technical requirements, timing for availability and access to workforce. But the intangibles were in play too.

“Just the attitude and welcoming nature of the people in Hopkinsville pushed it to the top of the list fairly quickly,” he said, noting assistance from the office of Gov. Andy Beshear and the Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, the office of the Hopkinsville mayor, Christian County officials and the South Western Kentucky Economic Development Council.

The area’s EV momentum is such that in early February 2023, 12 county economic development organizations in Western Kentucky announced they had joined forces as Kentucky Cornerstone to “market the region as a prime location for industrial prospects wanting to be near the electric vehicle battery production centers in Kentucky and Tennessee.”

“The Kentucky Cornerstone idea started in late 2021 after the Ford projects were announced,” said Amanda Davenport of the Kentucky Cornerstone and Lake Barkley Partnership. “All of our communities are along the I-69 and I-24 corridors connecting BlueOval City in Tennessee and BlueOval SK Battery Park in Kentucky, and we wanted to promote our region in a cohesive and collaborative way.”

Lin said the collaboration is evident as Ascend Elements’ new facility comes on line. Located on over 140 acres in the Commerce Industrial Park II, the 500,000-square-foot facility will begin operations in late 2023. With the potential expansion phases, the company noted, the facility would employ up to 400 people in a variety of roles — from engineers and chemists to warehouse associates and manufacturing operators.

“We’re in the middle of a global energy transformation and it’s critical that we produce lithium-ion battery material in the United States,” said Ascend Elements CEO Michael O’Kronley as the first dirt was turned for the new facility. “Our future energy independence and national security depend on it.”

The new facility in Hopkinsville will produce sustainable, active battery material (both CAM and engineered precursor or pCAM) for approximately 250,000 EVs per year.

I-75 Automotive Corridor Ready for Next Phase

How did the company get its name? Lin explained it in a memo last year: “For every dollar invested in battery manufacturing, we need to match the capacity of the battery ‘gigafactories’ with ‘giga-recycling’ plants,” he wrote. “This isn’t optional. It’s the necessary completion and closing of the open battery supply chain loop — creating a circular battery economy that can ascend elements, bringing them back to life, over and over again, as efficiently and economically as possible.”

In addition to its home base in Westborough, Massachusetts (near Worcester Polytechnic Institute where the company’s IP was developed more than a decade ago), Ascend Elements operates a facility in Michigan in addition to the new sites in Georgia and Kentucky. In terms of site selection, the EV revolution is strongly attracted to the same I-75 corridor that has served the larger automotive industry so powerfully for decades, with Kentucky at its heart.

How big is the opportunity?

Analysis released in February 2023 by IDTechEx shows that current plans and announcements for new cell production capacity from gigafactories will reach 3 TWh by 2030. U.S. battery and battery cell manufacturing capacity is expected to grow to 18% of global capacity by 2027 from approximately 7% in 2021. Plants within an easy travel radius of the new site in Hopkinsville come from players such as SK On in Kentucky and Georgia, Freyr in Georgia, Envision AESC in Kentucky, LG (in partnership with GM) in Tennessee, and Rivian, whose planned $5 billion plant is very close to Ascend Elements’ Georgia facility. A division of SK is one of several investors who recently helped Ascend Elements raise $300 million in equity and debt financing.

“There are hundreds of thousands of tons of this stuff in North America alone,” Lin explained. And it needs to stay out of the landfill — not only because of potential toxic chemical leaks, but because of the fire hazard. Lithium-ion batteries need to be fully discharged before disposal. Because some are not, they can be a frequent cause of fires at waste sorting facilities when they short-circuit. At the same time, the batteries contain a number of valuable elements that are becoming more scarce as battery manufacturing facilities multiply.

“There is so much scrap and end-of-life batteries that will be available,” Lin said, that even combining the capacity of Ascend Elements and its two primary competitors will likely not be enough. As of November 2022, about 44 companies in Canada and the United States and 47 companies in Europe recycled lithium batteries or planned to do so.

“The gigafactories are very hungry and need to eat,” Lin said of current demand for those valuable materials. Mining is meeting demand now as the market grows so fast there isn’t enough material in circulation to make recycling meaningful. But a decade from now, recycling will become a new source of raw materials. He anticipates a day in the not-too-distant future when EVs and batteries will be traded in just like mobile phones are today, with automotive OEMs and their service providers managing the closed-loop process for the greater good of the customer and the environment.

“Once it’s out of the ground, we ought to be doing everything we can to recycle,” Lin said. “Every kilogram we use is one less kilogram that you have to mine.”

Digging Up Deals

Every traditional battery has a positive and negative pole. But you’ll forgive Kentuckians if all they see is the plus signs. Since 2020, Kentucky has seen roughly $10 billion in EV-related investments, with more than 9,000 full-time jobs announced by companies within the sector.

Start right there in Christian County, where in addition to Ascend Elements, the region recently welcomed a $31 million, 33-job expansion from Canada-based Martinrea Hopkinsville LLC, a Tier 1 automotive supplier. The expansion is propelled by growing business with added production of lightweight, high-strength structural steel products for internal combustion engine and battery electric vehicles.

In December, Ford and SK On updated the public on their $5.8 billion, 1,500-acre BlueOval SK Battery Park project in Glendale, Kentucky, where a long-simmering megasite finally got its megaproject. Slated to start production in 2025, the site will create 5,000 new jobs in Kentucky.

Construction is on schedule at the two battery manufacturing facilities capable of collectively producing more than 80 gigawatt-hours (GWh) annually. It’s all part of Ford’s target of producing an annual run rate of 2 million electric vehicles globally by the end of 2026.

“BlueOval SK Battery Park will be at the core of the electrification of the North American auto market,” said Jee Dong-seob, SK On president and CEO.

“As both the largest economic development project in our state’s history and part of the biggest investment ever by Ford,” said Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear in December, “this project cements Kentucky’s status as the electric vehicle battery production capital of the United States.”

“Ford’s roots run deep in Kentucky, and BlueOval SK is going to help Ford to lead the EV revolution, bringing thousands of new, high-tech jobs to the Bluegrass State,” said Lisa Drake, vice president, Ford EV Industrialization. “Ford is building on more than a century of investment in Kentucky and its incredible workforce.”

The complex will train 5,000 new workers at the new Elizabethtown Community and Technical College (ECTC) BlueOval SK Training Center, located on site. The 42,000-square-foot center is the only co-branded learning facility within the Kentucky Community College System and represents a $25 million investment by the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

“Ford has been a pillar of the community in Kentucky for more than a century and now Glendale will write the next chapter,” said Lisa Slaven, Hardin County Schools Transition Readiness Director. “As an educator and member of this community, I view the building of BlueOval SK Battery Park as synonymous with creating new learning opportunities and skill sets for the careers of tomorrow for our students, our community and Kentucky.”

In April 2022, Japan-based Envision AESC announced a $2 billion investment to build a new gigafactory in the Kentucky Transpark in Bowling Green, located in Warren County. The 30-GWh plant will create 2,000 skilled jobs in the region, producing battery cells and modules for multiple global automotive manufacturers.

“The Bowling Green area has an outstanding automotive workforce today, as well as the future pipeline of talent needed, and we are excited to support this with new jobs in the high growth electrification segment,” said Envision AESC U.S. Managing Director Jeff Deaton. “The addition of this new facility will make Kentucky the new gigafactory capital of the U.S., well positioned to meet the forecasted growth of EVs and attract future investment.”

“The scale of this project is like nothing our community has ever seen before,” added Bowling Green Mayor Todd Alcott. “It’s phenomenal for the future of our region.”

The company will produce new-generation battery cells with 30% more energy density than the current generation, reduced charging time and increased range and efficiency for EVs, powering up to 300,000 vehicles annually by 2027.

The gigafactory will receive support in the form of up to $116.8 million from state incentive programs and up to $5 million grant-in-aid for skills training. It will be powered by 100% renewable energy, supplied by onsite generation and purchased locally from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

In a conversation in late 2022, Adam Murray, a target market specialist with TVA Economic Development, noted that TVA’s seven-state territory already has welcomed $17.2 billion in EV-related capital investment creating 17,500 jobs.

“At one point there were over $40 billion of EV-related projects looking in our region,” he said.

Plenty of those have moved beyond the prospect stage.

“Over the last 12 to 18 months, some of our OEMs have started to manufacture electric vehicles and then batteries after that,” Murray said. “Now comes the supply chain that follows those battery manufacturers — electrolytes, separators, anodes and cathodes — even as we’re still seeing activity from OEMs and battery manufacturers. At least once a month, a new company is expanding or locating in our region.”

Among other recent investors in the burgeoning EV and EV battery space:

- LOTTE Chemical in August 2022 announced a joint venture with LOTTE Aluminium to build a manufacturing facility in Elizabethtown to produce 36,000 tons of cathode foil, a type of ultra-thin aluminum foil that is a core material used in EV batteries. Cathode foil is one of the four major components of lithium-ion batteries. It supports the CAM that determines the capacity and voltage of the secondary battery, and at the same time serves as a passage for electrons. Company leaders anticipate demand for the material to increase by an average of 32% annually by 2030. The Hardin County operation located on 40 acres in the T.J. Patterson Industrial Park will be the company’s first aluminum foil facility located in the United States and is expected to begin operation in 2025. According to the state, the project also represents continued success of Kentucky’s pilot Product Development Initiative, as the site that will be home to LOTTE was approved for $500,000 in state funding in 2020 to support infrastructure improvements. The JV partners are both subsidiaries of LOTTE Group, one of the largest conglomerates in South Korea.

- That same month in that same town, South Korea–based Advanced Nano Products (ANP), a supplier of carbon battery nanomaterials used in electric vehicle battery production, announced it would locate in Hardin County with a $49.6 million investment creating 93 jobs to supply battery producers including BlueOval SK Battery Park (like Ascend Elements, the company intends to serve multiple battery makers in the region).

- “We are pleased to be part of the incredible momentum in the EV sector throughout Kentucky. Starting in 2023, ANP will start manufacturing efforts in South Korea, China, Japan, Poland and the United States,” said Dr. Changwoo Park, CEO of ANP. “Kentucky is a key logistical location for ANP for our continued expansion to become a global supplier to EV battery plants. We look forward to the successful production start of our Elizabethtown site and we hope to expand our manufacturing facilities in Kentucky in 2025 with continued growth of the EV sector.”

- Firestone Airide (the Bridgestone Americas subsidiary formerly known as Firestone Industrial Products) has moved forward with a $50 million, 250-job expansion at its plant in Williamsburg in Whitley County to increase production of automotive air springs in support of the growing EV market.

- In January 2022, Gov. Beshear announced Piston Automotive LLC, a provider of automotive assemblies including advanced electric and hybrid vehicle battery systems, would increase the scope of a previously announced $1.5 million, 50-job Jefferson County expansion, which now will create 117 full-time jobs with a $26.3 million-plus investment. Piston is a subsidiary of Michigan-based Piston Group LLC, led by former NBA player Vinnie Johnson and among the largest African-American-owned automotive suppliers in the United States. The company has operated since 2011 in Louisville and also maintains a facility in Georgetown.

As it happens, the massive Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky operation in Georgetown also announced more investment and jobs to support electric vehicle production.

“The progress being made in EV transportation and manufacturing will be transformative,” Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet Secretary Rebecca Goodman said. “It fits perfectly with the commonwealth’s energy strategy that strives to create a diverse and resilient energy infrastructure and encourages sustainable economic development amid a changing climate.”

Ascend Elements’ new Apex 1 facility will be located in Hopkinsville, Kentucky.

Photos courtesy of PRNewsfoto/Ascend Elements

EV Infrastructure Builds on Strong Kentucky Logistics Framework

Just as EVs require layers of complementary technologies, the transportation systems that support them do as well.

That’s why Kentucky in September 2022 received federal approval to develop a nearly $70 million electric vehicle charging network.

“Kentucky was already a leader in automotive production and the EV battery production capital of the United States, which is helping us create thousands of high-quality jobs for Kentuckians,” Gov. Beshear said. “Today, we are further cementing the state’s status as a leader in the EV revolution by beginning to build the charging station infrastructure that will enable EV travel in every corner of our commonwealth.”

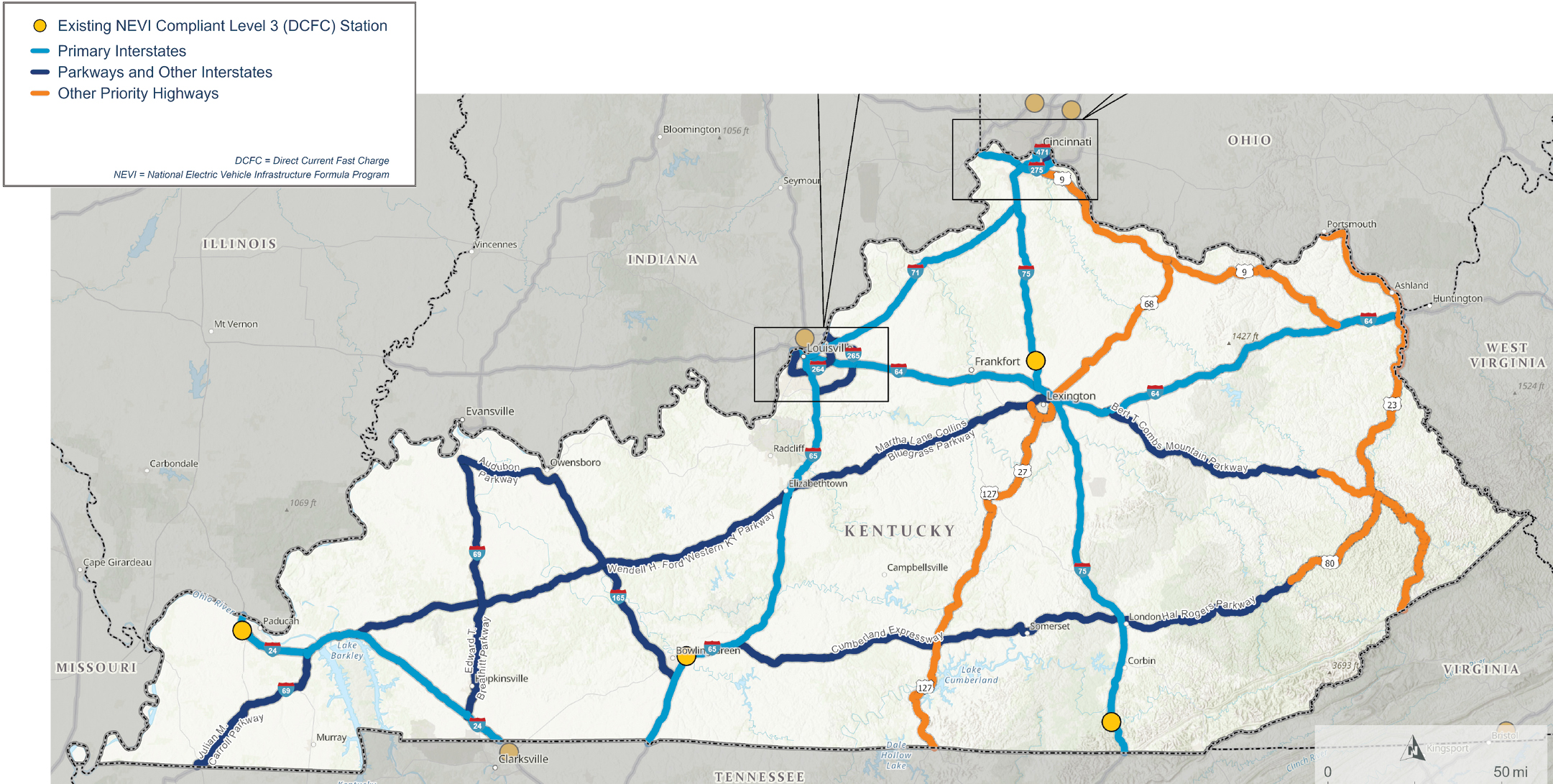

Kentucky’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment Plan outlines Kentucky’s high-priority EV corridors and was developed by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet (KYTC) in cooperation with the Energy and Environment Cabinet (EEC), Public Service Commission and Federal Highway Administration, along with input from hundreds of other agencies, organizations and interested parties. The approval secured federal National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) formula program funds. With matching funds, a total of $86.9 million will be available for EV charging infrastructure over the next five years.

“Initial NEVI funding must be spent to build out direct current fast-charging (DCFS) stations that can fully charge a battery in 30 minutes or less at interchanges along Interstates and parkways,” the state explained, with other corridors also identified to close gaps in the network.

In July 2022, the Federal Highway Administration approved Kentucky’s plan for Alternative Fuel Corridors (AFCs). As part of that plan, all of Kentucky’s 11 Interstates and eight parkways are now designated as EV AFCs (blue routes on EV corridor map). Fast-charging stations must be located no more than 50 miles apart along the AFC, not more than one mile off the AFC, must each have four ports at 150-kilowatt per port per station (600-kilowatt total), and must not be proprietary (stations limited to specific vehicles).

“Our goal is to have a statewide network of EV chargers by 2025,” said KYTC Secretary Jim Gray.