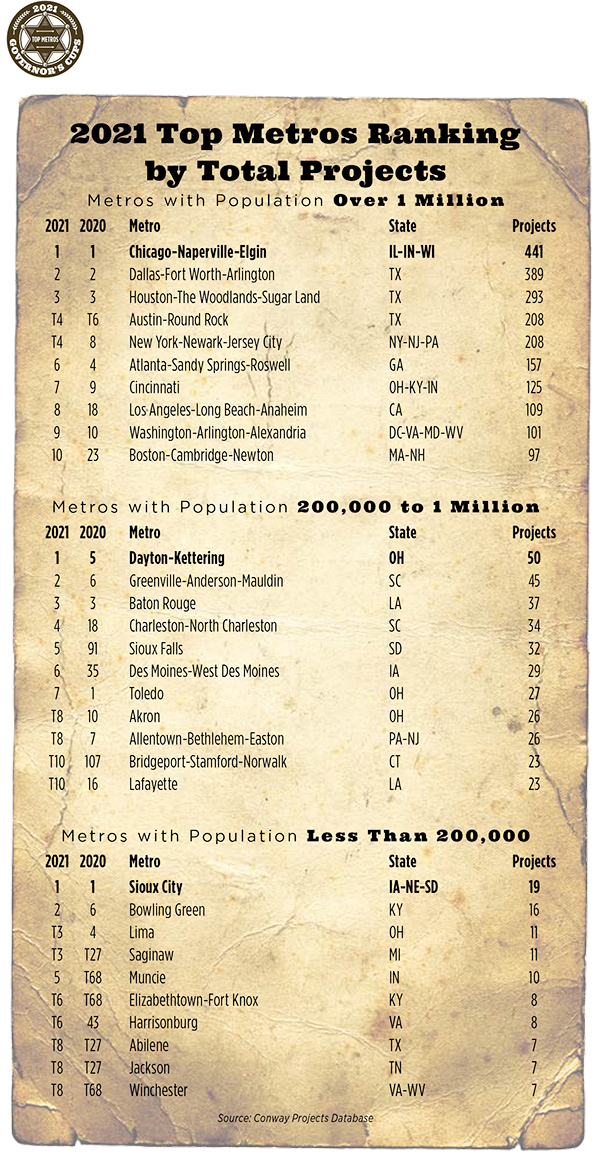

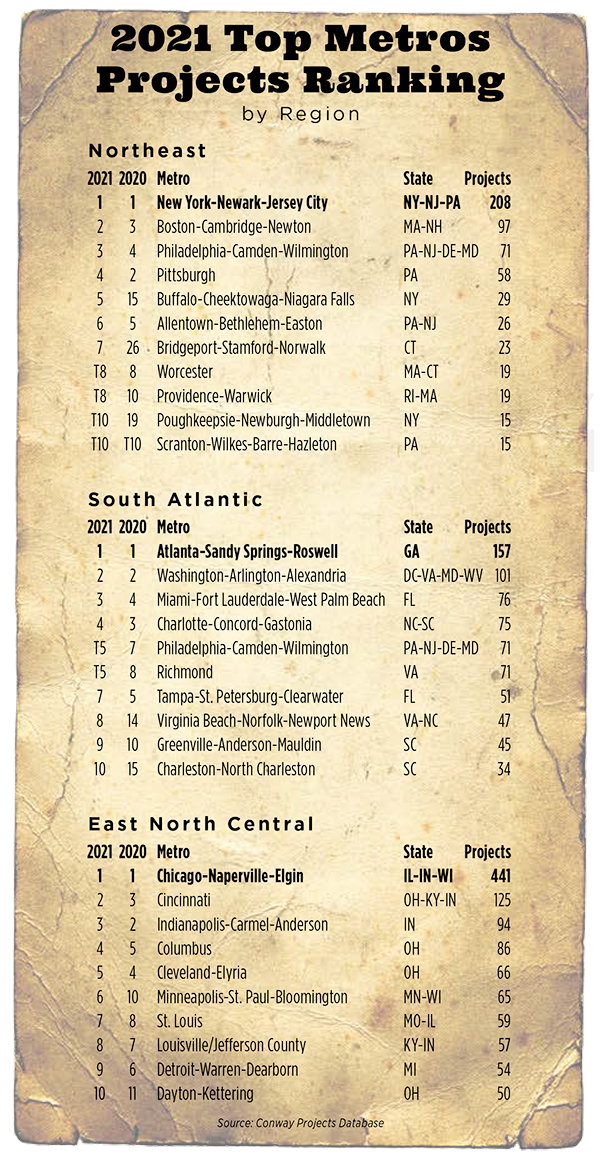

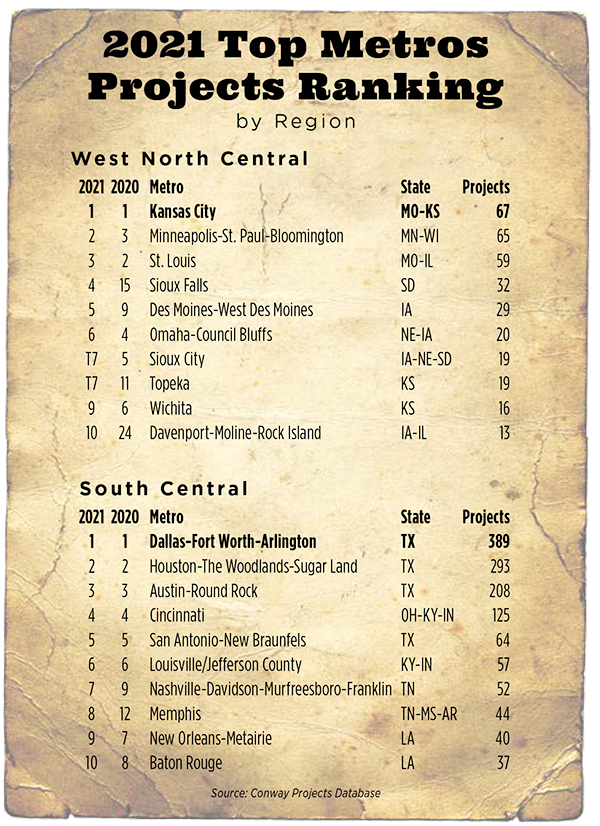

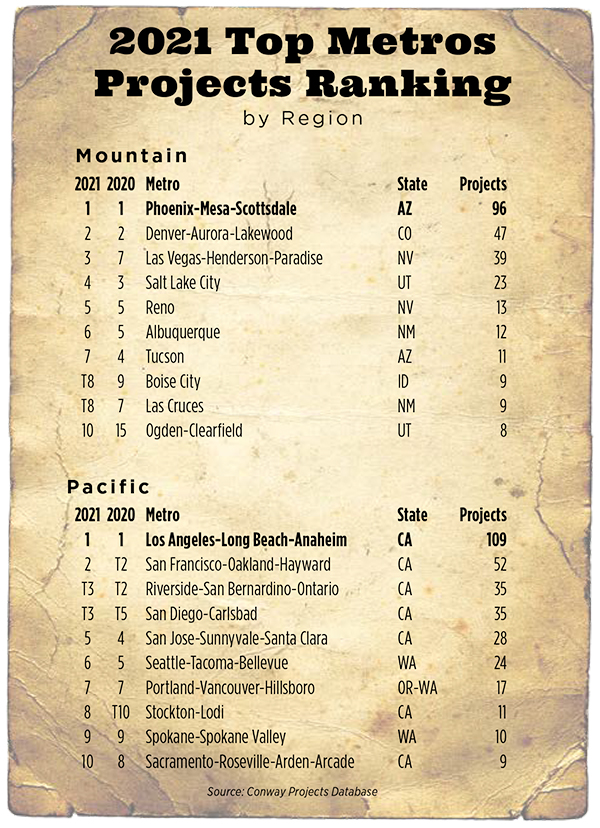

Capital investments surged in 2021, especially into Tier 1 Metros, with Chicago breaking its own record for qualifying projects accumulated over a calendar year. Led again by logistics and distribution, the Windy City’s haul of 441 such projects eclipsed the mark of 424 it set in 2016. Tier 1 metros have populations of 1 million or more.

Chicago’s uninterrupted run as Site Selection’s Top Tier 1 Metro began in 2013, when it seized this annual prize from Houston. In 2021, Tier 1s Phoenix and Indianapolis dropped out of our Top 10.

Boston-Cambridge-Newton, Mass. eked into the top ranks, with Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim returning to the Top 10 at No. 8 for the first time since 2017. The LA metro enjoyed a mix of investments in automotive (Vinfest, GM, Hyundai) aerospace (Aerojet Rocketdyne) and entertainment, led by the announced $1.2 billion overhaul of West Hollywood landmark CBS Television City by real estate developer Hackman Capital.

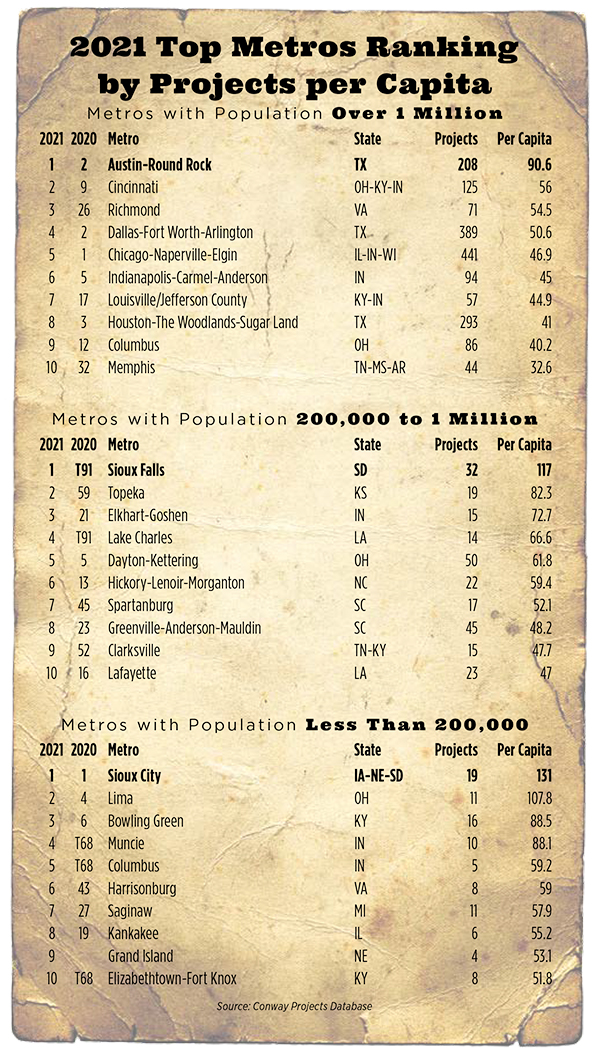

Some back-of-the-envelope math proves to be potentially illuminating, especially as the coronavirus pandemic recedes. Qualifying projects among the leading 10 Tier 1 Metros totaled 2,128 in 2021, a huge spike of nearly 50% over 2020. Those parameters, when applied to Tier 2 Metros (metros whose populations range from 200,000 to 1 million), reveal an annual jump of 25%, while — by the same aggregate — the leading 10 metros among Tier 3s (metros smaller than 200,000 population) actually witnessed a small decline in qualifying projects.

What does any of that mean?

“Anytime there’s economic disruption, capital investment projects will go to the areas of least risk,” says veteran site selector Tracey Hyatt Bosman, managing director in the Chicago office of Biggins Lacy Shapiro, the national site consultancy. “That can mean going to an established city, where the infrastructure is already there and maybe even the building. And with the long delays in construction, existing buildings are even that much more attractive.

“Then,” she notes, “we also have the national labor shortage, whereby bigger cities that have more people give the company — at least in theory — a better hope of finding the right workers. Also keep in mind the growth of e-commerce, which feeds the cities. If I’m going to put in an e-commerce distribution center, that’s where I’m looking.”

Behind the Numbers

Site Selection’s Top Metros rankings are based on accumulations of major capital investments in corporate end user facilities within a given core-based statistical area (CBSA) or metropolitan statistical area (MSA), as defined by the Census Bureau. Such areas can bleed across multiple jurisdictions, even states. Qualifying projects are tracked by Site Selection’s proprietary Conway Data Projects Database, which qualifies investments that meet at least one of three criteria: a minimum $1 million capex; 20 or more jobs created; or 20,000 sq. ft. or more of new space.

As we examine our Site Selection Top 10s, the farther down the three tiers one goes, the more volatility and perhaps even unfamiliar names come to the surface. But there’s much consistency as well. See perennially strong Dayton-Kettering, Ohio, in the top spot among Tier 2s. Tri-stater Sioux City, Iowa-Nebraska-South Dakota, extends its long streak of dominance among Tier 3s with the ever-present Bowling Green, Kentucky, right behind.

The metros that seem to come from nowhere represent their own kind of interesting. Among Tier 2s, Sioux Falls, South Dakota — with 32 qualifying projects — vaulted all the way from No. 91 in 2020 to No. 5 in 2021. Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, Connecticut, made an even bigger jump, going from No. 107 to T10. Into the Top 10 among Tier 3s march Harrisonburg, Virginia; Jackson, Tennessee, and Winchester, Virginia-West Virginia.

Chicago: You Win, Again

In February, forbes.com reported that, based on figures from the U.S. Census Bureau, Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport ranked as the nation’s top “port” for the first time ever. The Port of Los Angeles, struggling mightily during the pandemic, had ranked No.1 going back to at least 2003, forbes.com noted. O’Hare’s trade for 2021— gliding on the wings of cell phone and computer imports and shipments of medicines, vaccines and plasmas — topped $300 billion, an increase of staggering proportions. As Ross Perot used to say, “Think about that.”

For Tracey Hyatt Bosman, it’s more than just a neat bit of trivia. In trying to account for Chicago’s record haul of projects in 2021 and its recent record of dominance, Bosman lasers in on air transportation.

Nature’s Fynd, a Chicago-based alternative foods company, announced a major expansion.

Photo courtesy of Nature’s Fynd

“The impact of Chicago’s two airports is an asset that you can’t just create,” she says. “It’s moving people and it’s moving product. Especially given all the disruption to the East and West Coast ports, Chicago’s global air connectivity is number one for me.”

“… there are a lot of different sources for projects in Chicago.”

— Tracey Hyatt Bosman, Managing Director, Biggins Lacy Shapiro

Led by the sizzling, logistics-centered O’Hare submarket, which accounted for more than 20% of all industrial leases in the Chicagoland area, Chicago was the nation’s hottest market in 2021 for leases of 1 million ssq. ft. or more, according to CBRE. Nationwide, 12 of the 57 industrial leases of that magnitude were in Chicago.

“Chicago’s industrial market,” reported Cawley’s Chicago, the commercial real estate company in February, “continues to see record levels of demand.” Cawley’s cited what it called an “astounding” 12-month absorption of 33.7 million sq. ft. of industrial space, “well over twice the average levels seen over the past five years.”

The logistics and transportation side of the Chicago story is well known. Bosman is among those who believe there’s another narrative that needs to get out.

“Chicago,” she says, “has felt over the years that its manufacturing sector is underrepresented in the city’s brand. In fact, it’s huge. There are so many manufacturers — thousands of home-grown manufacturers in some cases — that there are a lot of different sources for projects in Chicago.

“Especially,” says Bosman, “if we were to isolate the last few years, BLS has seen tremendous activity nationwide in five sectors: food, e-commerce, general manufacturing, life sciences and tech. Chicago is very well positioned to absorb the activity that has been going on in all these sectors. Chicago just works for a diversity of projects.”

To that end, economic development officials trumpet Chicago’s emerging roles in developing models for quantum physics and clean technologies. In December, Chicago’s Clean Tech Economic Coalition, led by the hard tech and manufacturing innovation center mHUB, was recognized by the U.S. Development Administration for its potential to grow clean energy technologies that could accelerate the transformation of the region’s economy. CTEC was selected as one of 60 Build Back Better Regional Challenge finalists to receive a grant of approximately $500,000 to further develop proposed projects for potential funding up to $100 million.

“Illinois is poised to be the center of clean tech for the Midwest,” said Haven Allen, mHUB cofounder and CEO, noting that it is the first state in the Midwest to commit to carbon neutrality by 2045. “CTEC,” Allen said, “will align the state’s clean tech ecosystem to meet the demands of the national clean energy economy by growing new and existing businesses, accelerating job creation and dramatically reducing the environmental impact of major industries in Illinois.”

Also last year, Chicago became home to the first accelerator program in the country dedicated to startups focused on quantum science and technology. The University of Chicago’s Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship plans to invest a minimum of $20 million in the project over the next 10 years. In addition, Chicagoland’s Argonne National Laboratory and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have been designated by the U.S. Department of Energy as two of five new quantum research centers across the U.S.

For Chicago, getting out a more nuanced message suffers from the challenges posed by the city’s national reputation for violence. Whether the 24-hour “news” perception is fair or not fair, killings in 2021 climbed to a 25-year high. Michael Fassnacht, president and CEO of World Business Chicago, suggests that Chicago is increasingly eager to frame its own story, and aggressively, with more robust marketing efforts.

“In September of 2021, after Texas enacted socially conservative laws,” Fassnacht tells Site Selection in an email, “we ran a full-page ad in the Dallas Morning News, entitled ‘Dear Texas,’ where we offered our city’s progressive value proposition for anyone in Texas who might be considering starting a career, opening a company or relocating altogether to a city with their same values.”

Bosman says the more aggressive posture is a “really good sign. When I see them taking that on in a proactive manner, I take it as a sign that there is really interest and attention being paid to economic development.”

Also worth promoting, she believes, is Chicago’s vast cultural landscape, which has served to make it attractive to legions of young workers. As much of the Midwest and the state of Illinois continue to lose people, Chicago’s population actually grew from 2010 to 2020.

“There is absolutely a vibrancy to the city,” Bosman says. “That is why Chicago has been able to attract such a diversity of talents. The city has done well through this time where we’ve been focused on the millennial talent pool and now thinking about Gen Z. The cultural assets that Chicago has will always be there. They’re not going anywhere.”

And to Bosman, the City of Big Shoulders happens to have a disarming warmth that may tend to get lost, as well.

“One thing I’ve always found about Chicago is that it’s very down to earth. It’s friendly and ‘normal’ in sort of a stereotypical Midwestern way. Chicagoans,” Bosman says, “are really just Midwesterners in the big city.”

Dayton: The Wright Stuff

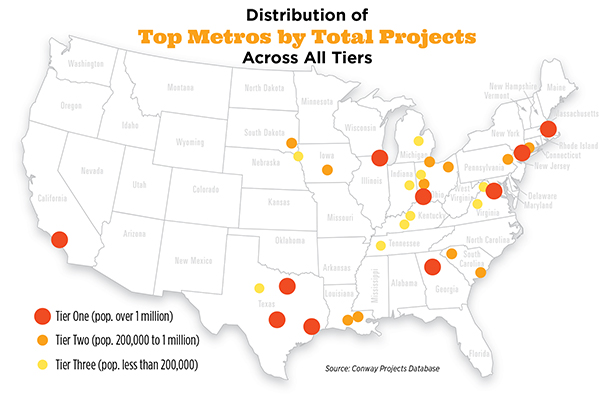

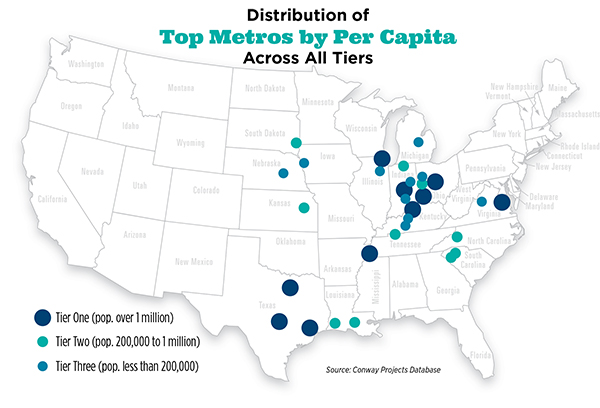

Taking a look at the accompanying map that depicts the dispersal of Top Metros across all tiers, it is easy to discern a certain concentration that occurs in the Midwest, where Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Nebraska and South Dakota all have cities, in several cases multiple cities, that rank among our Top 10s. That brings us to Dayton, a perennial Top 5 entrant. In 2021, Dayton tallied 50 qualifying projects, putting it five projects clear of Greenville-Anderson-Mauldin, South Carolina.

According to the Dayton Development Commission, the pandemic-challenged year of 2021 was nonetheless a record year for Dayton. In February, the Commission announced that the Dayton region last year set a record for the number of new jobs committed by companies building new facilities or expanding, with more than 4,264 new jobs and more than 3,298 retained.

As with many other perennial top contenders, the Dayton-Kettering MSA is blessed to have a long-time anchor that commands relevance now and is likely to do so in the future. In Dayton’s case, it is Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Remember the Dayton Agreement of 1995 that ended the civil war in former Yugoslavia? It was negotiated and inked at Wright-Patt.

“We continue to believe and invest in the greater Dayton region.”

— Larry Connor, Founder and CEO, The Connor Group

Established in 1917 with pioneering Dayton aviator Wilbur Wright in mind, Wright-Patterson is much more than just a slice of history.

“It’s our largest single employer,” says Jeff Hoagland, the Development Commission’s president and CEO. “We have over 32,000 employees just inside the fence, and the multiplier outside the fence is probably three- to five-X of direct and indirect. Wright-Patt,” Hoagland says, “has a $16.5 billion annual economic impact in the greater Dayton region.”

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center, a division of the U.S. Air Force, is in the process of completing a new $182 million facility on the grounds of Wright-Patt.

“They’ve grown,” says Hoagland, “by 100 employees a year for 15 consecutive years. If that were a private business, we would be rolling out the red carpet and the incentives. They are bidding billions of dollars of contracts out, and more and more of our companies are getting those.”

Even more important, according to Hoagland, is that Wright-Patt is fomenting the development of local technology companies such as JJR Solutions and Tangram Flex that are helping to enliven downtown Dayton.

And this being Dayton, there are other airports, too. In late January, the Connor Group, a Miami Township-based real estate firm, announced plans to expand its headquarters on the grounds of the Dayton-Wright Brother Airport, an investment expected to exceed more than $20 million. The new facility, to be known as “The Annex,” is to have the capacity to accommodate 56 new employees, while adding some 23,000 sq. ft. of office space.

“We continue to believe and invest in the greater Dayton region,” said Larry Connor, founder and managing partner. “Our company’s strategic growth has created the need for expansion. The Annex will create the space and opportunity to do that.”

Sioux City’s Ice Cream Rules

Hey, Mike. Thanks for the Bunny Tracks. No, seriously!

CEO of Wells Enterprises in Le Mars, Iowa, Mike Wells likes to tell the story of the founding of his family’s ice cream business, now the second biggest in the country — think Blue Bunny. In 1913, his great uncle, Fred Wells, was heading home to Chicago after an ill-fated attempt at homesteading in South Dakota.

“He got as far as Le Mars and he literally ran out of money,” Mike Wells says. Fred Wells managed to procure a horse and wagon and began delivering milk, soon to try his hand at making and selling ice cream. A century-plus later, Le Mars lays claim to “Ice Cream Capital of the World.” And Mike Wells knows his ice cream, having started long ago on the floor of the operation.

“During the pandemic,” Wells tells Site Selection, imparting perspective that would almost seem to be self-evident, “people fell in love with ice cream all over again. Ice cream,” he believes, “is the number one comfort food in the grocery store. The kids are all home. Families are sitting around the table together. Nothing brings joy like ice cream.”

At a time of heightened demand for his product, Wells faced pandemic-related staffing issues, a seminal challenge. In a way, it seems to have rocked him.

“What we learned in 2021, along with most other employers, was that the employment landscape has changed. The things that are important to people far exceed pay. We learned a few things around how we could do a better job of addressing what is important to our people. Flexible schedules. How we onboard new employees. Simple things like better varieties of food in the break rooms.”

But it didn’t stop there. Wells went as far, he says, as to restructure the company leadership to get him closer to what he believes is important.

“I found myself caught up making decisions that impacted people without really understanding the total context and impact. And so last September, we changed our organizational structure. That has freed me up as chief executive officer to spend the majority of my days with people. Now, I spend an average of four or five hours a week walking the plant floor and reacclimating myself to what actually happens here. In my 45 years here, I don’t think I’ve had this much fun.”

Still, the worker shortage is real. Even in a metro as vibrant as Sioux City, whose toes dip into Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota.

“We haven’t seen any significant population growth in a number of years, and the pandemic put a further strain on that,” says Wells. “We see the need for population growth, and we believe quality of life is at the center of that.”

With his business and his family’s ties to the Sioux City region, and as chair of the regional Siouxland Initiative, Wells has skin in the game, including a $1 million donation to the Plywood Trail, an initiative that would link Sioux City and Le Mars by bicycle path, a potentially delightful jaunt of maybe 25 miles through fertile, green fields and over a succession of bridges spanning creeks and larger streams. Wells envisions neat things springing up along the way, especially in the pass-through towns of Merrill and Hinton. And how about snowmobiling among pubs in winter?

“People pay extra to be connected to bike and walking trails,” he has come to believe. “We think that it creates not only the economic potential of having those destinations, but we also believe that, as we think about how we grow our population base, there’s no reason that those communities along the trail don’t actually start to build new houses, becoming really great places to live. Great places to live, work and play. Right here.”