Many companies worldwide have chosen to locate in logistics clusters, so what can enterprises learn about these communities that they do not already know?

The answer is “a great deal,” for two reasons. First, compared to clusters of other industries — Silicon Valley (high-tech), Hollywood (entertainment), or Wall Street (financial services) for example — logistics clusters are not as well understood by many governments, supply chain managers, and corporate real estate professionals. Second, trends in international trade support more investment from both private- and public-sector organizations in these agglomerations of logistics, distribution and transportation firms.

One of the main motivations for writing my new book “Logistics Clusters: Delivering Value and Driving Growth” was to bridge these information gaps and help companies evaluate logistics clusters when selecting locations for their logistics and manufacturing operations.

Logistics clusters can be found in most countries, generally near consumer markets, in central points, or in close proximity to ports and airports. And they play host to a wide range of organizations, including the logistics arms of enterprises, third-party logistics services providers, distribution companies, and freight carriers. These entities have grown in both number and size over recent decades, and they have become an integral part of global supply chains; both enabled by globalization and enabling its continued effectiveness. Yet the reasons for this success are not generally appreciated, and they often underestimated in terms of the economic significance of logistics clusters.

“Postponement operations — finishing the product as late as possible in the manufacturing process to take advantage of more accurate demand information — are a natural fit for logistics clusters.”

The Feedback Loop

In general, industrial clusters are communities of co-located companies, enjoying high productivity and increased competitiveness due to tacit knowledge exchange between them, collaboration opportunities, the development of specialized local labor force, the move of suppliers to the area, the increased sway they hold over local governments, and the relative ease of starting new companies in the region. All this is true for logistics clusters too, but these clusters provide additional benefits to their members.

First, the growth of logistics clusters is self-reinforcing, becoming more valuable to their participants the bigger they are, which in turn attracts more companies and further growth. Many elements of this positive feedback loop are rooted in the economics of freight transportation. As these clusters grow, they attract higher freight volume, enabling transportation carriers to use the largest conveyances at a higher rate of utilization. Both factors reduce the cost per ton-mile hauled.

Furthermore, higher freight volume enables the carriers to offer better service levels in terms of high frequencies and more direct services to/from more locations. Low freight rates and high service levels attract more companies, feeding these factors further. Large freight volumes also allow carriers to find follow-on loads more readily, reducing wait time and increasing their productivity, which again leads to reduced transportation costs. Further, by raising the efficiency bar, logistics clusters promote global trade, which increases the demand for cluster-based services and stimulates further trade growth.

Logistics cluster tenants also derive benefits from the interchangeability of transportation and logistics assets. Since equipment such as railcars, containers, trailers, and airplanes come in standard sizes and shapes, it can

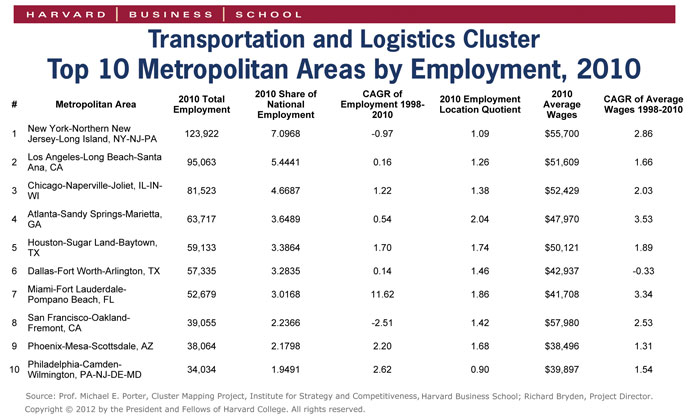

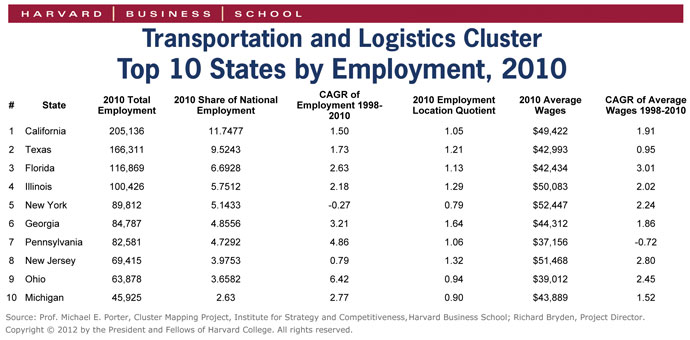

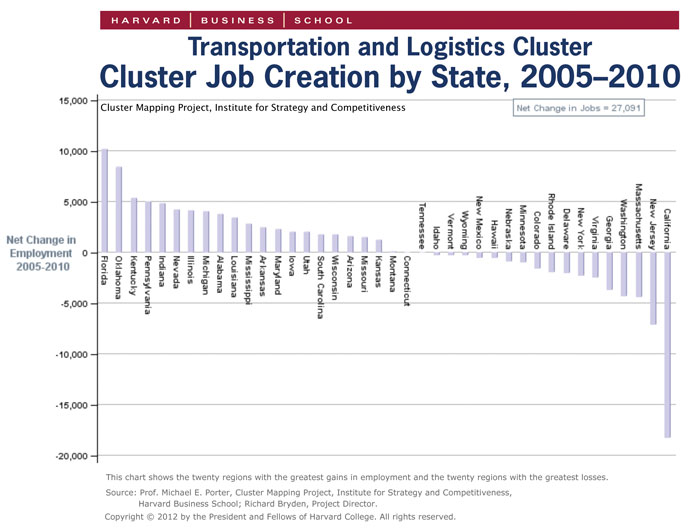

The charts, derived from the Cluster Mapping Project at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, offer some indicators from established and up-and-coming logistics territories in the United States. — Ed.

be shared by the community. The same goes for the logistics expertise that resides within these groupings. Sharing resources in this way enables the incumbents to withstand the demand variations and accompanying fluctuations in freight flows in the industries they serve.

An attribute of logistics clusters that is often overlooked is their potential to create jobs. The port of Rotterdam, for example, employs 55,000 people directly and 90,000 indirectly. In the U.S., Los Angeles County supports more than 360,000 jobs in logistics. The Memphis International Airport supports 220,000 jobs in the local economy, 95 percent of which are tied to cargo operations. In fact, more than one in three jobs in the Memphis area link to the airport.

The employment opportunities in logistics clusters are wide ranging. There are blue-collar jobs in areas such as warehousing and transportation; white-collar positions in IT, customer service, and management; and work associated with value-add activities including light manufacturing and repairs.

Two characteristics of jobs in logistics clusters are particularly important nowadays. First, they are difficult to offshore. The economics of transportation favor large conveyances over long hauls and small ones for the “last mile distribution.” In addition, late-stage customization of products that is carried out in many clusters needs to be located in close proximity to end markets. Second, these jobs are not tied to the vagaries or the business cycles of any one industry, since logistics serves many industries in the same cluster.

In many cases, logistics clusters are also building highly valuable expertise in environmental sustainability. These hubs increase the efficiency of freight transportation modes, which lowers the carbon footprints of supply chains.

Spanish In Position

Benefits like these translate into competitive advantage for cluster-based companies. Moreover, as the model continues to evolve, the returns are likely to be greater.

Take, for example, Caladero, the largest processor and distributor of fresh fish in Spain, located in the PLAZA logistics park in Zaragoza (midway between Barcelona and Madrid). The company sources fish from boats around the world — from the waters of Nova Scotia to Peru, Scandinavia, India, and Japan. When it receives information on the incoming catches, Caladero contacts grocery store chains and retail fish markets to negotiate orders and to craft retail promotions.

The company consolidates these various catches in major airports around the world. It pools all of its fish supplies from around the southern part of the African Continent in Johannesburg’s international airport, for instance.

The operation meets two important goals. First, it justifies the use of very large — and hence more cost-efficient per ton carried — cargo planes to ship the product to Spain; and second, combining multiple catches in this way buffers Caladero against fluctuations in the amounts of fish caught by each boat.

The company’s processing and distribution plant is located in the PLAZA logistics park near Zaragoza, Spain, the largest park of its kind in Europe. Naturally, for its customers to get the “taste of the sea,” Caladero has to fly the catch from around the world and move the cargo quickly from the incoming planes to the processing distribution center. To this end, its giant 633,000-sq.-ft. (58,805-sq.-m.) facility is so close to the runway that the company had to sink it 66 feet into the ground to prevent aircraft from clipping the roof as they touch down.

Locating in PLAZA offers the company a number of key advantages. First, the park is centrally located (only ~300 km. [185 miles] from the four largest cities of Spain: Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Bilbao), and it offers a congestion-free airport and excellent transportation links to the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. Second, Caladero has opportunities for collaboration with other companies in the park. For example, the company works with one of its neighbors in PLAZA, Inditex, parent of fashion retailer Zara, to provide backhaul for the mammoth Boeing 747 cargo planes that transport fish for Caladero. Zara garments fly back to Johannesburg on a return trip of the same plane that brings the fish to Spain.

Beyond Goods Movement

Another business opportunity that has become increasingly important in logistics clusters is providing value-added services. At its Louisville Worldport hub in the U.S., UPS employs hardware technicians to repair Toshiba laptops, for instance. Similarly, ATC Logistics repairs and refurbishes mobile phones for several brands at its facility in the AllianceTexas logistics park in Fort Worth, Texas.

Logistics clusters are also convenient for preparing product retail display. For example, UPS Supply Chain Solutions in Louisville handles all of Nikon’s distribution of photographic equipment for the Americas. This work includes kitting: adding accessories such as batteries, chargers, and promotional material to cameras before the units are shipped to retailers.

These postponement operations — finishing the product as late as possible in the manufacturing process to take advantage of more accurate demand information — are a natural fit for logistics clusters. Until 2012, sports apparel manufacturer Reebok was the principal supplier of jerseys for National Football League teams in the U.S. The company never knew which NFL team was going to be “hot” from one season to the next, and demand for particular jerseys can spike with the week-to-week performance of certain teams and players. Reebok handled these last-minute orders by sending blank shirts to its distribution center in Indianapolis, where the shirts were finished off when the demand for specific items became known. Moreover, Indianapolis is a logistics cluster with 1,500 logistics companies — including FedEx, which has its regional air-freight hub there — giving Reebok plenty of shipping options.

A different class of value added-activity takes place upstream in the supply chain — again involving tasks traditionally performed by manufacturers. This type of work leads to the formation of industrial clusters driven by logistics needs in close proximity to an OEM plant.

An example is DHL’s support for the Audi Neckarsulm assembly plant in Germany. The logistics services provider does not just send materials to the plant; it assembles door panels from inventory stored in its warehouse 5.8 kilometers (3.6 miles) away. DHL sequences the units based on Audi’s production schedule, and delivers them to the auto plant as part of a tightly coordinated, just-in-time/just-in-sequence manufacturing operation.

The DHL/Audi logistics paradigm exemplifies the evolution of global supply chains, in that it supports a finely-tuned manufacturing model geared to minimizing cost while maintaining a high service level to the end customer. It is this paradigm, along with global trade trends, that will drive the future growth of logistics clusters.

International trade volumes are expected to grow over the next few decades. As the dynamic economies of developing countries such as Brazil, China, and India expand and prosper, their middle classes will continue to swell, creating demand for products and services, at low cost and high level of service.

But this growth comes at a cost. Increasing consumer demand puts a severe strain on natural resources. How to promote rising living standards without jeopardizing the well-being of the planet is one of the biggest challenges faced by humankind today.

Global supply chains, the arteries of world commerce, play a critical role in finding solutions to these problems. And the logistics elements are charged with the task of efficiently delivering more necessities and goods to more people in more places at low cost and at minimal environmental impact per unit.

As a key component of these operations, logistics clusters have a role to play. Companies and governments that understand this, and appreciate the unique advantages of these communities, will be much better positioned to meet the challenges of global growth.

Prof. Yossi Sheffi, the director of the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, is the author of “Logistics Clusters: Delivering Value and Driving Growth” (MIT Press, October 2012).

Prof. Yossi Sheffi, the director of the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, is the author of “Logistics Clusters: Delivering Value and Driving Growth” (MIT Press, October 2012).